How a delicatessen menu taught me how to understand how my son – and my church members – learn.

While I was writing this, I had several conversations, mostly with my oldest son, Arlo, a college instructor, about the third grade retention law in Tennessee and how students often do well in reading or math skills but not in testing even though it is through standardized testing that it is determined whether or not they will advance or be held back to repeat third grade. The teachers I know work so very hard to help each student and if we are going to have standardized learning (i.e., all students of an age studying the same thing at the same time) then we will have standardized testing is a necessary evil. Having taught the students who ended up in Study Skills classes in a community college because after high school they were still not ready for college-level work, though, I know that brilliant people may never learn to test well. Many among us will go through life believing they are not smart when in fact it is simply because they learn differently and do not have access to the learning environment that suits them. We certainly cannot expect our teachers to be able to teach to all learning styles, but all of us can learn from those around us how they – and we – learn better, i.e., we can figure this out together.

Always Learning

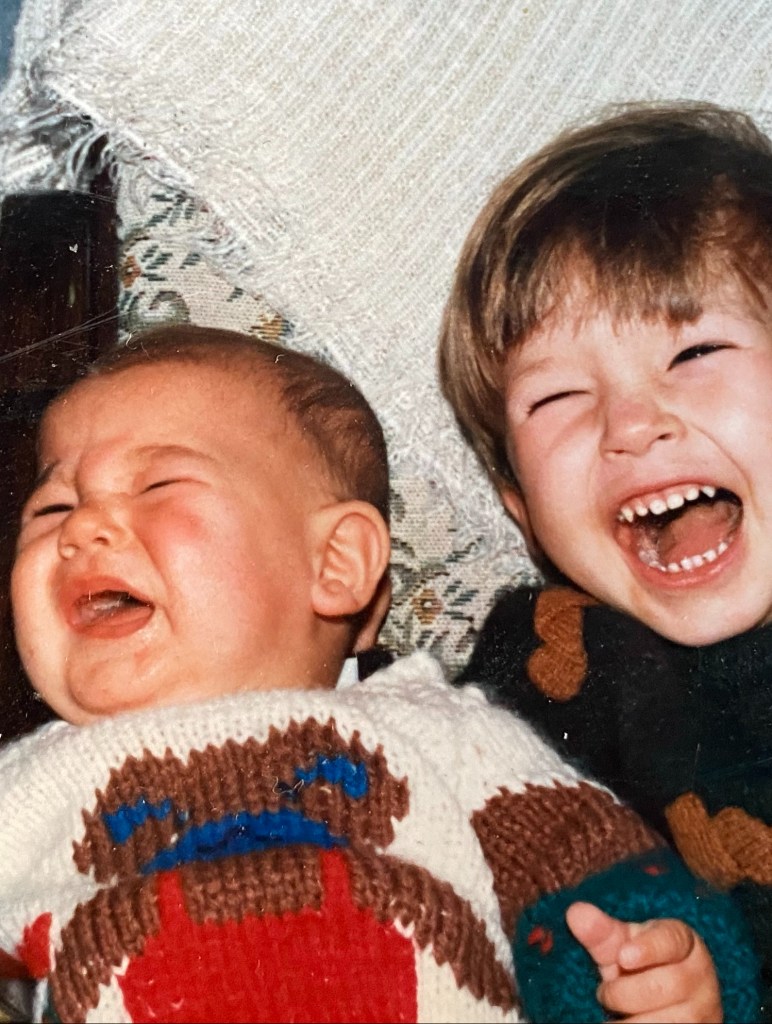

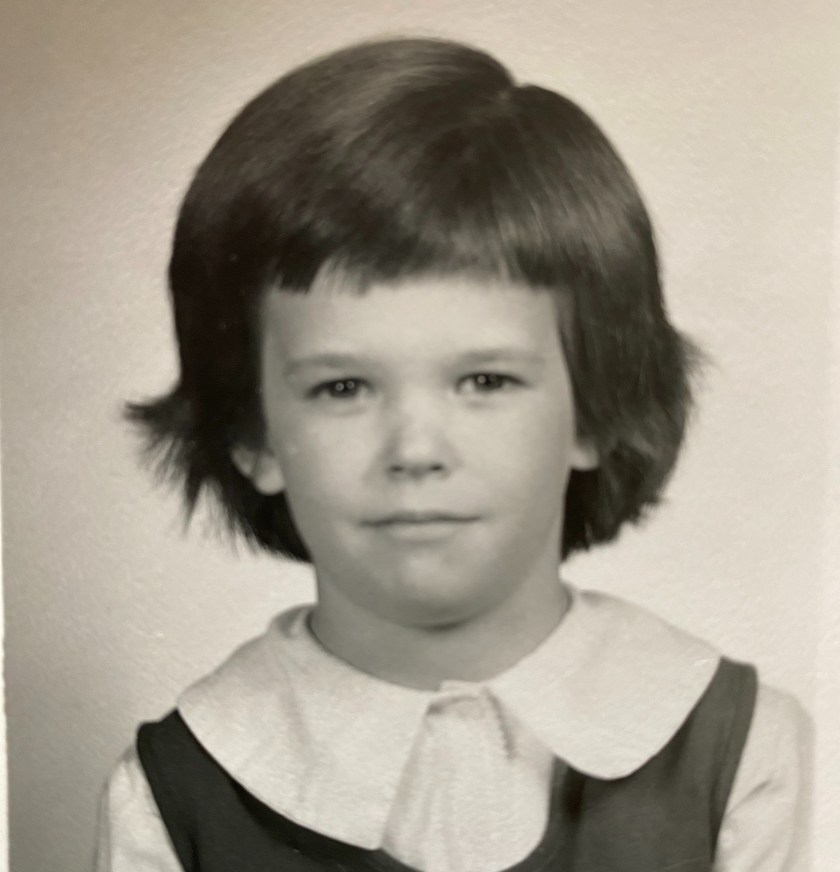

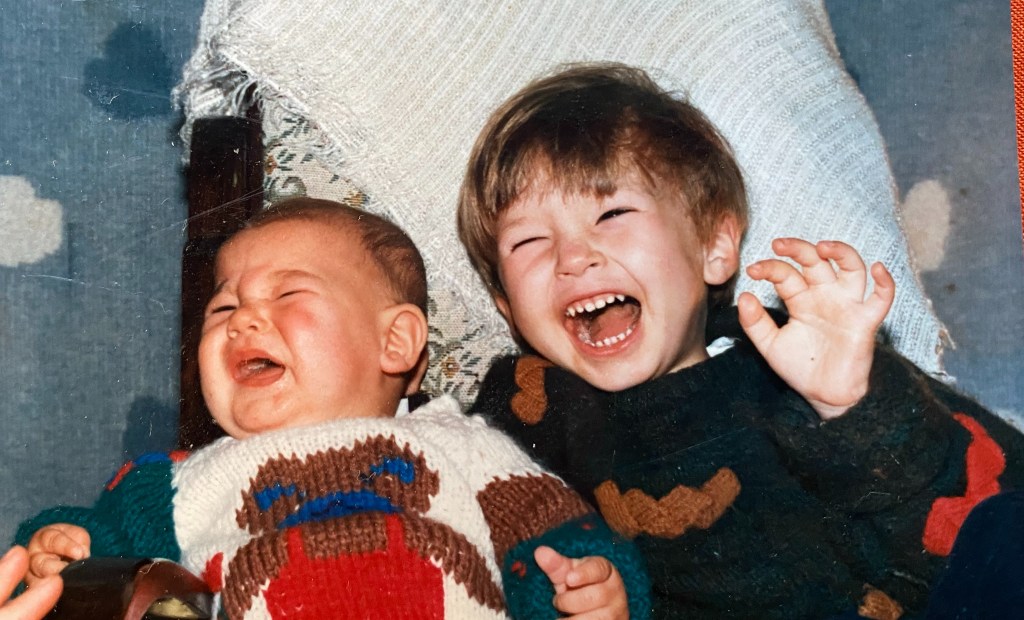

No one was more surprised than I was when my youngest son – the shy one, the one who barely spoke until he was three – agreed at around age nine to be the puppeteer for our children’s time in worship. Until that point, most of the church knew him only as the child peeking out from behind the pastor. Turns out, Spencer didn’t speak much until he was three for a couple of reasons: first, he couldn’t get a word in edgewise with three non-stop talkers also at the dinner table; and second, like his older brother, he was born when we lived in Japan where he heard less English than Japanese. We moved back to the states before he was one, so he was uprooted and plopped down in Tennessee just when he was learning to speak. Changing how his brain was wired likely took a minute. The first real words he uttered came as a full sentence, though, or actually, as a question from his favorite movie: “Who ya gonna call?”

Once he started talking, we would find out what a quick and dry wit he had developed. I had introduced a children’s time during worship early and I was reminded regularly I was not in control, often by my own children. The morning I told the children about Jonah being swallowed by a giant fish, then “thrown up” onto the beach, Spencer jumped in with his commentary.

“Could have been worse,” he said. “Could have come out the other end.”

He was eight when we got to the first church I served, just old enough to go to see his friend Charlie one town over for an overnight stay. Evidently, however, he could not sleep, he confessed when I picked him up the next day. Charlie’s mother was as surprised and concerned as I was; what had he done all night while everyone else slept?

“Watched infomercials,” he said.

I looked to Charlie’s mom who seemed worried I might be upset. “Well, you’ll get a nap in the car ride home,” I offered, shrugging.

My son said thanks and goodbye, then stopped at the back door long enough to tell Charlie’s mom, “Oh, your George Foreman grill will be here in three weeks.” Then he walked out the door, leaving both adults bewildered.

That dry sense of humor and sense of timing would serve him well as a puppeteer. I planned to use the Children’s Time to both entertain and teach. We had a large red dog puppet, whom we renamed Jeffrey and whom we decided would be allowed to ask questions no one else dared ask. In his debut, our puppet first told what would become my favorite joke.

“What’s the difference between roast beef and pea soup?” he asked.

I shrugged and asked, “What?”

“Anyone can roast beef.”

It took a minute, but we both waited, expecting to hear the chuckles move across the room slowly; first, though, we heard the roar from the back pew. One of my church members, Ray, loved the joke apparently. A few months later, I would visit him in the hospital and laugh myself because nearly every person who helped me find him that day would ask, “You mean the guy with the pea soup joke?” A year later, he would succumb to the illness that had sent him to the hospital. Sitting in the visitation parlor of the funeral home, I would hear the joke enough to prompt me at the funeral service the next day to ask how many in that room knew the difference between roast beef and pea soup. Nearly everyone raised a hand.

On that first Sunday of the puppet’s debut, once the ripples of laughter had died down, Jeffrey asked me, the pastor, what I was wearing under that robe? I had not worn a robe before that, but frankly hoped the robe would solve the ever-challenging task of what to wear when preaching.

“Why, I’m glad you asked,” I said. Then, as I reached down to lift up the hem of my robe, I saw Jeffrey had covered his eyes and was exclaiming, “No, no, no…!” Jeffrey was a hit and became one of our most effective teaching tools. Using a puppet was in part a response to all I had been learning about how to help my people learn something about themselves and their God.

Lessons from the Deli

Opportunities to learn what worked for teaching and what didn’t flew at me from all directions at that church; the toughest part was catching all of them and seeing how they were related. A delicatessen menu, for example, taught me about my son, my sister, father and my church. I knew my son was smart; I just didn’t know why he was so often angry until we visited the new delicatessen in Gallatin. We met up with some friends for lunch and we were standing at the counter as a group, staring at the menu, which was written on the back wall of the restaurant behind the counter where the sandwiches, soups and salads were prepared. Usually, when we ate lunch at drive through restaurants, menus sported pictures and we all knew what they were called because we could all sing the jingles we heard during commercial breaks while we watched our favorite television shows. At the new deli, even I felt the pressure to peruse the menu quickly, so I turned to my youngest son and asked if he saw anything he might want for lunch. He looked at me, bewildered. It was a glorious moment of vulnerability; normally, he would have barked at me for singling him out for help. At that moment, though, I realized he did not see what I saw. I saw “Salads,” in larger, bold lettering, for example, then “Chicken,” “Tuna” and “Garden” salad categories in smaller lettering followed by even smaller paragraphs with descriptions for each salad. He saw lots and lots of jumbled letters.

“Want a ham sandwich?” I offered, knowing what he liked, and told him he could have it on white, wheat or rye bread and he chose rye just to be adventurous.

“Can I have mayonnaise on it?” he asked.

“Absolutely,” I said, “and no tomatoes. Chips?” He agreed to chips and soda.

I made a note, though, to visit our local library and there I was grateful to find out about different learning styles and how those often mirror and/or drive the different ways we relate socially in the world. Some of us learn just fine the way most subjects are taught in school; others struggle. I personally learn by taking what is presented and being able to then restate it in my own words. In Chemistry in high school, for example, my teacher would walk me through the problem at hand and it always made sense to me in that moment. If I did not get a chance to retell within a short time the solution to the chemistry problem, though, it would be lost to me. I may have initially understood it but I would quickly lose grasp of the solution if I had not written it down and been able to explain it myself. Only if I wrote something down, then retold it in my own words, would I learn what had been presented. Fortunately, that was easy enough to do in most classes growing up. I personally kept great notes and studying for an exam was a matter of going over and over my notes until I could nearly recite them word for word and then recreate them for an exam. Just explain something to me orally, though, then exit and the understanding would leave the room with you.

My son, I realized, learned by watching and repeating what he’d seen as well, but by doing, not writing and reading. When he was five, we watched him recreate a rocket tower with his plastic building toys while watching one of his favorite movies about the Apollo 13 moon mission. When the rocket took off during the movie, we realized that our son’s rocket tower fell away in stages in exactly the same way the real tower did, something none of the rest of us had even noticed. I do believe that he would have been likely labeled with some sort of “learning disorder” had we not homeschooled our sons. As it was, what I read suggested he simply needed some understanding of his learning style and what might be getting in the way of his learning. He needed me to recognize, for example, that he found distracting those modern textbooks with their colorful pages and art interspersed with words. Simply placing a piece of colored plastic across a textbook page, though, rendered the colors and art less distracting. Turns out, he was among many who struggled because we as a culture had decided it was somehow helpful to readers to spice up the visuals in our textbooks and magazines. Some of us enjoyed the art; some of us were too distracted to be able to read. Different styles.

Spencer also needed information: when you read a textbook, a menu or a newspaper, you start with the largest letters. Might seem intuitive, but not everyone approaches the world in an intuitive manner and our world is richer precisely because we are not all the same. To read a newspaper, you look first at the headlines; on a menu, you choose categories like soup or sandwiches. Once you decide whether or not you want a sandwich or sports, you look to the next largest groups of letters and decide if you want a tuna sandwich or if you want to read the previous days’ scores. Smaller letters give you details about the avocado sandwich you chose, or where the baseball scores can be found. Even smaller lettering leads you to what else you could have on the sandwich or which team won the game or match.

Learning styles also affect our approach to the world and our relationships. Often, my son simply needed information to help him navigate.

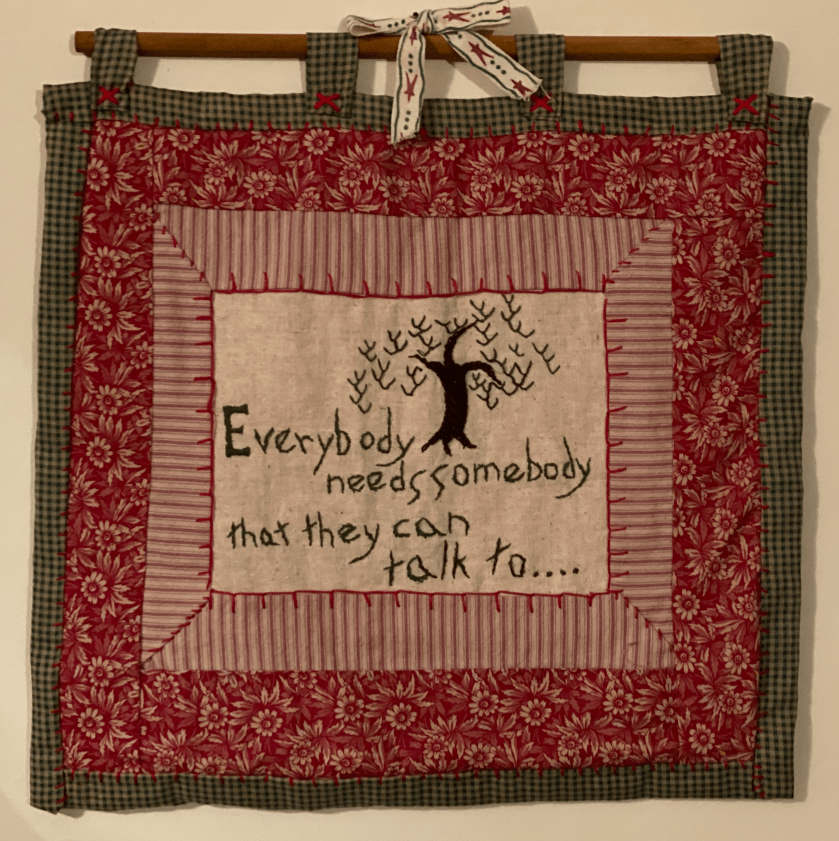

Turns out, when it came to relationships, the same was true. Often, he simply needed information to help him navigate. He asked once what to do when someone was crying. Before, his tactic was to walk away and get someone to help. He wasn’t uncaring. Far from it. He was worried he’d hurt someone more by saying or doing the wrong thing when they were already vulnerable. I suggested a plan: stay close by, and, if you know them well enough, put a hand on their shoulder or arm and ask if there is anything you can do to help. He said thanks and that was that; I thought he’d forgotten about it really until a couple of years later when said he had tried that with a friend and had been relieved to find it had really worked.

What I had learned was that my son needs information while others learn visually or by hearing. Tragically, seldom do pastors learn how the people around them learn. My son taught me why so many of my family members and congregants might be frustrated. Suddenly, for example, my understanding of one member bragging that he’d finished college “without ever cracking a textbook,” changed. He’d turned that into a plus when it had actually been a hint to his learning style, one not often supported in schools then. Quickly, I understood why our children’s time was often the only part of the worship service people remembered in the beginning. The story or our puppet wasn’t teaching theology; it was just funny, but funny can be theological if you’ve let your guard down expecting a funny joke.

On one of the first Sundays using Children’s Time, I talked in the sermon about “schadenfreude,” the idea that we take some joy in others getting their due or at least not getting more than us. For the children’s time, I had brought wrapped pieces of hard candy and shared it with the children, but I only had three pieces, so the last child in line got none. When he protested, I explained, “I ran out but at least three of the children get some so we can be happy for them, right?”

“That’s not fair,” he wailed.

“Well, then, perhaps no one should have candy,” I suggested, snatching back the candies from the other children before they knew what was happening. They were, of course, bewildered by quickly changing fortunes. “Is that better?” I asked.

He grinned. “Yes!”

Of course, everyone laughed (but I immediately regretted the lesson we were all learning at his expense.) In that moment, the pastor learned to think through the children’s messages more carefully. The child felt better but the others were sad and bewildered until I said, “Wait. Look! There’s another piece of candy here after all.” All the children eagerly accepted their candy and went back to sit with their families. before their fortunes changed again.

Likely none of the children heard the sermon that day but the adults were primed to hear my sharing about my own schadenfreude.

Ironically, I admitted, I had seen this in myself that morning driving to church. I was sideswiped and nearly run off the road by a speeder. My reaction to that bit of driving aggression had been far from pastoral. To make matters worse, when I passed the same guy a little later getting a ticket just a few miles down the road, I gloated loudly! My schadenfreude, or joy, was that he was “getting his due.” The adults in the room understood the idea better and had it reinforced because of Children’s Time. They understood better then the prophet Jonah who was not happy to discover that God wanted to forgive all the sinners in Nineveh; Jonah wanted to see them “get their due.” We usually want others to get justice while we ourselves get mercy and forgiveness. That’ll preach, as they say.

Over the years, then, using all I learned, I not only used the Children’s Time and our snarky puppet, but also worked to craft sermons heavy with stories and illustrations because so many of us only remember the stories we hear or the “word pictures” we encounter. “Show. Don’t tell,” works. Maybe too well. After a couple of years of working to find and add stories to the sermons in hopes people would take something away from worship, I got one of what would feel like daily lessons in humility. At an Administrative Council meeting, a member offered the devotion before the meeting proper using a story I’d told three weeks earlier in my sermon. “Ah,” I thought, sitting back and smiling, “they DO listen.” But no. Once she’d finished her devotion, she handed me her notes.

“Feel free,” she said, “to use that in a sermon. It’s a great story.” Sigh.

Bonus free joke from the adult Spencer:

What is the difference between a tuna, a piano and a glue stick?

I don’t know. What is the difference between a tuna, a piano and a glue stick?

You can tuna piano but you can’t piano a tuna.

Okay.

But what about the glue stick?

That’s what everybody gets stuck on.

Leave a comment