Pulling death out from the shadows and examining it in the light does not make death happen. In fact, it does just the opposite. Thinking about death, learning about it and accepting it, makes life happen.

Virginia Morris, “Talking About Death Won’t Kill You,” Algonquin Books. Kindle Edition.

Death is a funny thing. And I don’t mean in a dark humor kind of way but, rather, funny as in strange: we all do it, and, these days, we all know we ought to muster up our courage and talk to our loved ones about what we know is coming at some time, and yet few of us do.

Talking about how we want to die and what needs to be done when we do is a gift to our families and friends, kind and considerate; sometimes that’s the last gift we give loved ones. Pastors and health care workers and counselors encourage us to start the conversations early but far too few of us ever get our courage up to start, even though we surely love our families.

We often don’t even talk to our loved ones

AS we (or they) are dying.

The first person I sat with who was dying, died alone in a hospital room while his family waited out in a waiting room. That was thirty years ago. We did not know how to help him not be afraid and nothing we said could ease the fear but no one wanted to name that or claim it either, so we talked around him when we were in the room. We talked about the weather, the dog, the cost of eggs, anything except death and eventually most went back out into the aptly named “waiting” room. I, just starting out as a pastor, stayed in the darkened room with this man who no longer wore his own clothing but rather a hospital-issued and worn cotton gown and asked for some socks that weren’t neon blue or orange and didn’t have those silly dot on them or some salt for the instant potatoes and who was just plain furious. He was angry about sox and pajamas and dying without some damn salt and without any choices: no choices about dying and not even any choices about how he would die. Thus far, as a pastor just starting out, I had read and discussed one book about how to minister to someone who is dying and could remember none of what the damn book said. I drove home that night screaming in my car. I had not signed up for that, and I was unprepared both for his anger and mine and this helplessness we shared. The journey into ministry was going to be rougher than I ever could have imagined.

Once I’d calmed down a bit, a pastor with more experience offered this simple advice: “Next time,” she said, “name it. Fear. Uncertainty. Anger. Questions. Whatever is in front of you while you sit there, name it.” There was a time when I would have discounted such a ridiculously simple suggestion, but it turned out to be great advice. In fact, in any difficult situation, naming whatever is in “in the room,” especially if it is scary, lessens the fear and opens up the space for questions, laments or even the jokes, all ways of sharing.

I buried about a couple of dozen members of that church over the next few years, including a suicide, my 18-year-old communion steward and a couple who had been married for more than 75 years and who died within a week of one another. All of those deaths brought up questions, and I tried to name what I saw and reassure us all that talking about death would not kill us. Most of those folks’ deaths happened fairly quickly, but one member of that first church took almost a year to die after receiving what he called his “death pink slip.” Over that year, David showed an entire church how to die a good death. Diagnosed with metastasized prostate cancer already destroying his back and ribs, the construction engineer who could no longer build houses started building birdhouses. He built hundreds of them in the months he was dying. His mind and his hands still moved well and in sync and he was grateful when his friends’ eyes lit up. He designed bird homes that celebrated the University of Tennessee for a Vols fan, several that looked like our little white country church and one I requested that mimicked a Lincoln Log cabin.

More importantly, though, as David died, as he dealt with the diagnoses, the treatments and the rapid onslaught of decay and death, he shared. He talked about what was happening to him to everyone who visited him. He taught us what the Hospice folks were teaching him, even describing what death might look like, how he might have some better days right before he died and what to watch for in his breathing as death grew nearer. In short, he did not hide or try to protect us from what was happening. He named all of it and we are grateful for this evidence of his courage and love for us.

Because of David, I also found a great resource and over the years referred to it both for personal help and also to preach and teach. In, “Talking About Death,” Virginia Morris addresses so much of what keeps us from these important discussions. First of all, she says, “Pulling death out from the shadows and examining it in the light does not make death happen. In fact, it does just the opposite. Thinking about death, learning about it and accepting it, makes life happen.”

When I started this project a friend of mine called me, all upset. She felt that this endeavor was not only morbid, but dangerous. By studying death, she said, I might make it happen. A friend of hers had died of cancer while studying Portuguese death rituals. I, too, might be on a suicide mission. This subject was better left untouched. Her concerns may seem a bit odd at first, but they are not unusual. Death is the boogeyman, hiding in the shadows of our bedrooms, arousing all sorts of anxieties and fears—some valid, some silly, some we don’t readily admit even to ourselves. Most of us can’t imagine the end of our existence as we know it. We dread the process of dying, the pain and disability. We panic at the thought of leaving loved ones, or having them leave us.

Morris, Virginia. Talking About Death (p. 7). Algonquin Books. Kindle Edition.

What Did COVID teach us?

So many died during COVID alone and unable to be comforted by family or friends and we are more aware now than ever of the importance of being there for one another.

NEVERTHELESS, we struggle with starting the conversations before we are ill, before we are hospitalized, before we need hospice care.

Part of the issue is that we simply don’t have to talk about death much anymore. We simply do not talk about death, not even in churches even though a church seems like the best place to talk about death.

In so many of those little churches we attended, all of the “Saints” who’d gone before were buried all around the church in the cemetery just outside the doors. Every few months, we would have “supper” on the grounds, meaning we spread our biscuits and fried chicken legs and pickles on platters on old checked table cloths on top of the graves of our ancestors, who were buried all around us.

There was no pretending they weren’t there with us, bodies underneath and souls swirling overhead, whispering in our ears, reminding us all they’d taught us and all they’d done, good, bad or just human. Don’t slouch. Eat your greens, too. Wipe your fingers on that napkin and not on your shirt, young man. These were the folks who’d walked through those cemetery gates and into that old wooden sanctuary each week and they had taught us how to follow those 10 rules Moses brought down from the mountain AND to turn that other cheek. Still, they didn’t have to create a moment to talk about death because they reminded us of it every Sunday and during revivals as we entered that sacred space.

Today we don’t have those reminders. We do not see the cycle of life and death firsthand on a daily basis now. We do not wring the chickens’ necks and pluck them ourselves; few of rely on butchering hogs to have food for the winter, and we no longer prepare loved ones’ bodies for burial ourselves. We have people called to and trained to do these tasks and so the majority of us will never touch any dead body, never be faced with the need to handle a lifeless body, never have to be reminded we too will die, never find an occasion to talk about our deaths.

Easy for You to Say.

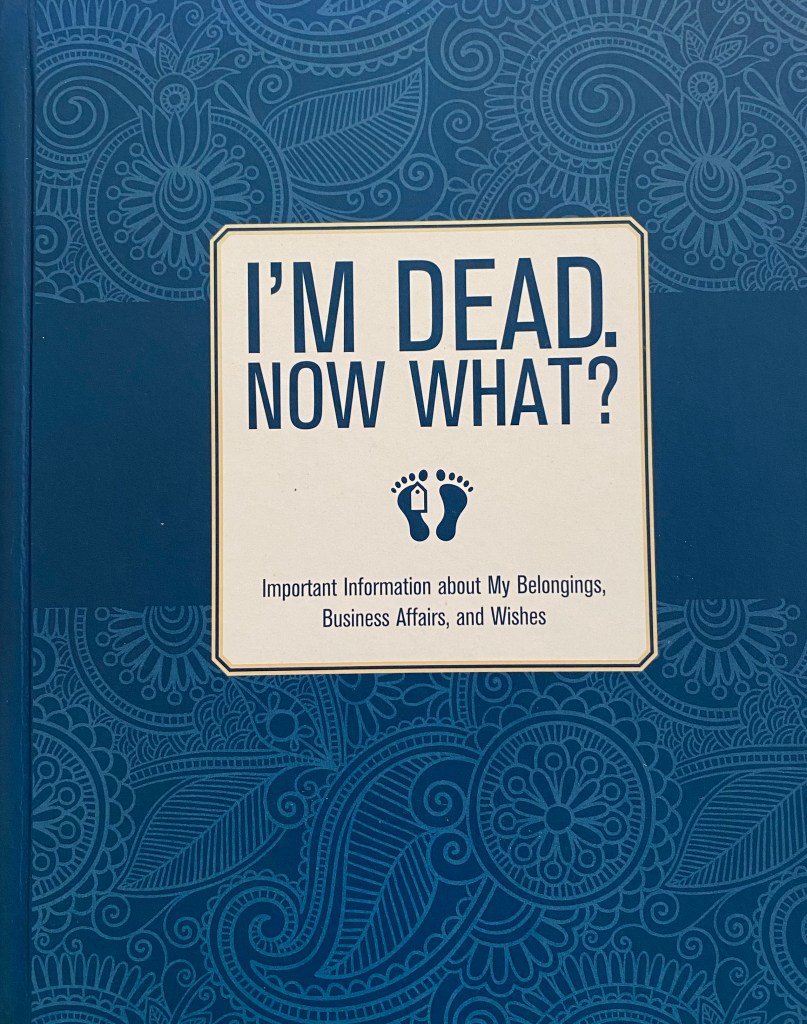

You might be thinking that as a retired pastor, of course, I have lots of experience sitting with people who are dying, sitting with the family and friends of someone who has died and just talking about death in general. That is true, but all that professional experience did not make it any easier to start the discussions with my own family or to begin the work personally. In fact, I am embarrassed to say that it was a neighbor who suggested the book that started me on the process for myself and my family, by suggesting the book she’d found: “I’m Dead, Now What?” (See below.)

I want to offer some suggestions, then, some topics and some resources to help you do what is one of the most loving things you can for your family: discuss with them, prepare and plan so they are not left with the burden when you are gone or can no longer help. We can do this.

Start with the easier stuff.

If talking about death at all is just difficult for you, start with putting your papers in order and maybe your mind will become more used to the idea of realizing there will be a day when you (posthumously) say, “I’m Dead. Now What?” When you are gone, will your papers be in order? Will whomever is left to pay the bills, deal with property, take care of Fido or make other decisions know where to find what they need? Thankfully, there are wonderful resources for that as well. Starting here will often help us begin the many conversations we need to have around our own deaths.

Passwords, please. Can I get an amen?

If nothing else, safely providing a list of the seemingly thousands of passwords we all have now is one of the greatest gifts you can give these days. Don’t forget to tell them what the site is for the password; you know how you have spent hours trying to get back into your Netflix account. Think about how that’s going to work when it’s time to close out the account and stop the automatic draft for that times about fifty or a hundred, depending on how many apps and accounts you have.

Talk About How You Want to Die

We all hope to die at a certain way if we are honest and think about it for a moment and sharing that with one another around a kitchen table is a way to learn about one another.

Some of us want to die quickly, instantly. Some of us only hope for no pain. Many of us in my culture hope to die at home in our own beds surrounded by family and friends. Some of us hope to die with a silk parachute inflating overhead one last time; others of us hope to die in in satin ballroom shoes, our hips responding to the beat on the congas as a Latin band plays a cha-cha. Still others of us would love to take our last breaths in the arms of a lover. Some of the sweetest couples I’ve known debate who should go first: some do not want to be left alone after a longterm companion goes but most are more concerned about their sweetheart and hope that the other will go first so they are not left alone to grieve. They would take that grief upon themselves.

Consider doing a bit of research, then sharing.

In Japan, at least thirty years ago when I lived there, everyone in the neighborhood chips in to help pay for the costs of a neighbor’s funeral knowing that everyone else will do the same when their own time comes.

Funeral traditions there offered us a number of occasions to talk about dying and our own deaths. Once, a neighbor came to visit after her father had died and shared with me about the funeral since I had not been in town on the day of the funeral. I remember trying to put my finger on what was wrong as we sat and looked at a picture album of the funeral gathering and ceremonies until I realized that what was strange for me was that there was a photo album of the event. I had never known anyone to photograph a funeral.

There’s some fascinating and/or disturbing historical examples of cultural differences around death, such as mummifying and burying with everything you’d need to survive in the afterlife, including, sadly, your pets, and others we pray have been banned forever such as the Hindu custom of a wife immolating herself on the funeral pyre of her dead husband.

Write down your information first, then your wishes.

Think about what you want for a service, write down your wishes and share them with a family member and a pastor or another family friend who can help when the time comes. What are your wishes around being kept alive? Wishes around resusitation, extreme measures and even feeding tubes are much more difficult for family members if they are not aware of your wishes.

Do you want certain songs included in your service? Have a favorite verse? Talk about what you want and need or don’t want. Tell a pastor or trusted friend who can help you when you need to let your loved one die the way they’ve chosen, whether that means no , no on every possible intervention, i.e., their choices as best can be honored.

Clean up after before yourself.

In some societies, sorting through all your belongings, “death cleaning” is an established tradition. They are aware of the stress and pain of leaving all our “stuff” behind for our family to have to sort and clear and give away or sell or keep.

“Death cleaning,” or “döstädning” is a Swedish term that refers the process of downsizing before you die. Death Cleaning, explained in “The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning” is an gift you give your family. Sorting through, clearing out, giving away or selling all the “stuff” we can accumulate throughout our lives is an indication, the author writes, that you love your family enough to clear our unnecessary things and make your home nice and orderly well before you think the time is coming closer for you to leave the planet. The idea is that our spouses and children or grandchildren are not burdened with what can become a beast of a process, yet another source of pain for those grieving us when we’re gone, yet another indication that we didn’t want to talk about death.

(Magnusson, Margareta. The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of Clutter (The Swedish Art of Living & Dying Series) (p. 2). Scribner. Kindle Edition.) Also available on Amazon.

Start the conversation any way you can.

We all face it; people all over the world face it, but not always in the same manner, using the same customs, so, I’m thinking maybe talking about cultural differences around death and dying might be a way to start a conversation.

Did you know that those death masks, usually made by taking a cast of a person’s face after their death, were often kept as mementoes or used for the creation of a portrait or perhaps a scupture after the person had died and been buried. That could open a conversation. A lock of hair often is kept, a tradition started by Queen Victoria after the death of her husband. Tiny brooches might hold cremation ashes. Do you want to be cremated? This is the time to make sure a loved one knows that.

Just start.

Finally, to start the conversation, if none of the suggestions above have spurred you to sit down with your spouse or children or companion or pastor or priest yet, here is a poem I wrote after sitting with a man at my last church who was dying. Perhaps you can start simply by sharing this poem over a cup of tea, a pint of beer or some lovely scones your neighbor dropped by to share. “Hey,” you can say, “I read this poem about death and dying today and it made me think. Can I read it to you and you tell me what you think?” You get a yes and maybe some discussion will follow. Have some questions ready. Maybe a version of “Would you rather…?” Would you rather be buried at sea or on a mountain? Would you rather have everyone sing happy songs at your funeral or maybe tell their favorite joke?

Every time I have spent time with someone who is close to death, I recognize I am closer to my own death and my own fears and though both death and the fear of dying creep ever closer, neither seem to crowd out the peace I have found in talking about, in naming, what is before me, even death. It’s pretty much the one thing we all have in common. Let’s talk!

Sitting with the Dying I used to think sitting with someone who's dying took courage. Now I think it is much more selfish than I might ever want to admit. It is an act of hope, yes. If I am honest, though, the hope is that someone else will sit with me when I'm the one who's dying. There is prayer but the prayer is that someone who knows me will wipe the drool from my chin when the time comes. There is the seeking of promises, guarantees, bartering if necessary, so that someone whose face I used to recognize will cup my face in the palm of their hands when I cry like a baby, or pluck the hairs from my upper lip because even a dying woman deserves to feel pretty. The first time I sat with someone who was dying, I went into that dark room because no one else would and because I couldn't bear anyone dying alone. Except now I know we too often do anyway. Still, if there's any comfort to be offered there, I will selfishly offer warm, gentle and soft touches if only because I know I want the return. I confess then that sitting with someone who's dying is a selfish act for me. It is my way. A way to make the world the place I want it to be, where no one dies alone if only because I cannot bear to live in a world where we do. ~Jodi McCullah 2022

4 responses to “Talking About Death Won’t Kill You.”

-

Thank you for these reflections, Jodi. As a hospital chaplain, I’ve found that many people who’ve been told “some bad news” (that they’re dying), desperately need someone willing to help them work through just what that might mean for them and their loved ones in our culture in which even thinking about death seems to be taboo.

-

I was raised with grandparents who took me to their church’s dinner on the grounds. One of my favorite places to photograph is a cemetery. I imagine all of the lovely lives and interesting people there. And, my Mother taught me that there are far worse things in this life than dying. Thanks for the lovely article.

Leave a reply to A. Getty Cancel reply