Some of the greatest moments in life, I believe, are when you find out you are not the only one who does “that.” You’re not the only kid in class who likes to blow bubbles in her chocolate milk or the only student who questions why you should wear a dress to school on picture day when you hate wearing dresses and no one ever sees your dress because you’re always in the back row for pictures. Once, on a phone interview for a job in Florida, I mentioned that most of my friends “up here in the north” seemed to believe that living in colder climates builds character and people who want to live in warmer places are just lazy. The employer simply said, “Come on down; you’ll find plenty of hardworking folks here; they just happen to like burying their toes in the warm sand.” I remember thinking, “I’ve found my people.”

One of my most affirming moments occurred a few years ago while watching a movie that was set in southern California. A woman was sitting in heavy Los Angeles traffic on her way to work when the road began to shake and seemed to begin rolling. Her first response, once all the motion ceased, was to pop open her trunk and change from her fashionable black pumps into a pair of hiking boots. She evidently kept in her trunk for just such an emergency, or at least the character did. She must have known she’d likely have to walk through streets filled with debris, and the boots were just one of the survival tactics she’d either learned firsthand or been taught. She was prepared.

I remember nothing else now about the movie except that I wondered if she also kept some water and maybe a first aid kit and snacks in her trunk. What I loved was that she wasn’t some hiker out on the Appalachian Trail for weeks; the character must have been created by someone familiar with earthquakes who understood that we never know when or where we’ll need to run for our lives. It would be several years later before I would learn that boots in the trunk was a common response for survivors of trauma and abuse. I don’t know if the woman in the movie was supposed to have grown up with a scoutmaster for a father, or if she was a trauma survivor, but she embraced the boots in the trunk. She didn’t think it was weird.

Boots in the trunk, a “go” bag by the bed…

I was a teen when I realized not everyone slept with a “go bag” next to the bed in case a speedy escape became necessary in the middle of the night. After five decades of being teased by others for it, though, I was especially grateful to finally learn that lots of other trauma survivors sleep with shoes under the bed, a wallet or purse with meds, money and that handy Swiss Army knife by the bed, so that in an emergency, they do not waste precious survival and escape time locating footwear or a flashlight. Finally, I could stop being embarrassed that I preferred to sleep in something I knew I could wear outdoors in case of a fire or an earthquake or tornado. I could stop hiding the fact that I think about not wanting to have to run into the dark barefoot and thus be even more vulnerable in a crisis. My “go bag” has been a reasonable and healthy response to the lessons of my childhood where I was taught to be afraid of the dark and it is also a reflection of a strong instinct to survive. Instead of being embarrassed that I startled so easily, I became proud of my Swiss Army knife and I became grateful for those survival instincts. Plenty of children do not get out.

Escape Artists

I know some people who were abused or whose childhood was traumatic seek vengeance and long to hurt the one hurting them, and even hurt others in an attempt to ease their own pain, but my instinct has always been to escape. When my siblings and I were young, they seemed unaware that following the rules meant escaping the belt or the hair brush. As we grew older and taller, I knew to stay well away from my parents’ and even my siblings’ arguments because they so easily slid into the violent responses we’d seen modeled. I mostly escaped broken bones and stitches by escaping as a child and teen. Later, I applied the same tactics to job losses and failures and broken relationships because I knew when to escape, and how to – most of the time – make an exit before the explosions.

Because I could escape, none of their crazy dust landed on me. I know without a doubt that is one reason I survived and got this far. Too many children who grew up like we did never get very far from the crazy, never get too many steps out the door. Maybe that is because they had not managed to stay arm’s lengths away as children and teens; maybe their scars left them less equipped to walk away when they were old enough; maybe their backpacks were just too heavy to carry another step.

Sadly, few if any adults were able back then to recognize this behavior as a survival technique and, thus, necessary. I once attended a junior high church retreat. Our parents sent us away to every camp and retreat that was offered. My brother and sister hated those camps. In contrast, I eagerly grabbed a bag and hopped into whatever car was taking us away from whatever house we were living in at the time. At that particular junior high retreat, though, the girls’ leader accused me of being like a “wolf.” Because I was being quiet, she accused me of preparing to “pounce, to attack,” when the opportunity arrived. I’m really not sure what kind of attack she thought I was planning. I remember just staring at her while she accused me of cooperating with some kind of evil. She was only half wrong, though, which meant, of course, that she was half right. I wasn’t preparing to pounce, though; I was preparing to escape, trying to figure out when that might be necessary. Sadly, it felt like escape was too often necessary and, after a while, became a way of life.

I wasn’t preparing to pounce, though; I was preparing to escape. Sadly, it felt like escape was too often necessary and, after a while, became a way of life. Photo, 1964.

A counselor once asked me how I had survived the turmoil, upheaval, illnesses and chaos of my home. Since I’d already told her about how often I had simply walked away, I was confused. I know now she wanted me to relate to her how I knew when to get the hell away from my mom or dad or brother or sister or myriad boyfriends. The fact is, in the beginning, I became a girl scout. Well, actually a boy scout. Okay, both. Being a “girl scout” meant being good. Being good meant usually no one noticed me and, if I followed the rules, usually no one would hit me. I would certainly never give them a reason to hit me.

Being a “boy scout” meant being prepared. Since we had moved so many times before I was sixteen, it wasn’t like we didn’t have practice packing. I kept my bag and shoes by the bed because they kept me feeling like I had some power to escape if I needed. I knew when to leave because I was what counselors called “hypervigilant.” I watched folks around me like a hawk. That was what concerned the youth leader at the junior high retreat; she did not recognize the behavior as a survival tactic developed over time in response to threats; it was somehow easier for her to imagine a teen as evil than to consider one of the parents in the church might be a predator, I guess.

Live Like a Refugee

The more I worked to find healing over the years after I finally escaped my family home, the more I found like-minded souls who also seemed to move about more than others. My first husband and I were both nomads when we met. “You Don’t Have to Live Like a Refugee” by Tom Petty was the soundtrack of both of our lives at the time. We had both been traveling quite a bit when we separately landed in a writing class and met; even nomads and escape artists settle down for the odd semester. By then, we’d both traveled all over the US and overseas and had both served in the military. We decided to settle down together, to create an alliance, to have each others’ backs; we might have imagined at the time that we’d be more settled, but we found then there were some things about being nomads we still liked and so we promptly moved to California, then to Japan, then to Tennessee, anywhere but where we grew up. So much for no longer being refugees.

Changing Tactics

There came a time, however, when I no longer had the luxury of escape, of running, because our two sons meant there were others I needed to protect and escaping might mean leaving them behind and that was not going to happen. Needing to protect others complicated escape plans, for sure. We taught our boys never to climb up a play structure if they could not make it down without help, to meet up at the back gate if there was ever a fire and we would not let them sleep upstairs until they were big enough to climb out a second story window onto a porch roof and then jump down to safety. Protecting them changed everything. I’d explain it by talking about driving over the huge bridges spanning the Ohio and Missississippi Rivers. We had to drive over both of them at the confluence of the rivers near Cairo, Illinois, every time we went north. Driving over those bridges was frightening enough for me personally but became hellish when I had children and their safety became most important. For myself, to calm my fears as I drove into the monstrous structures crossing those wide and churning rivers, I had developed a bridge survival plan in case the car somehow went into the water: wait for the car to fill up, open the window to swim up and then try to float on the current until I could get to land. With two small children, however, that plan would no longer work. Suddenly, I would need to take two precious little persons with me through that drill and, well, there was not a good time to try to talk to them about that plan and besides, it would most assuredly traumatize them so I prayed extra hard instead that the bridge engineers had done their jobs well and other drivers would keep their distances as we crossed over those bridges.

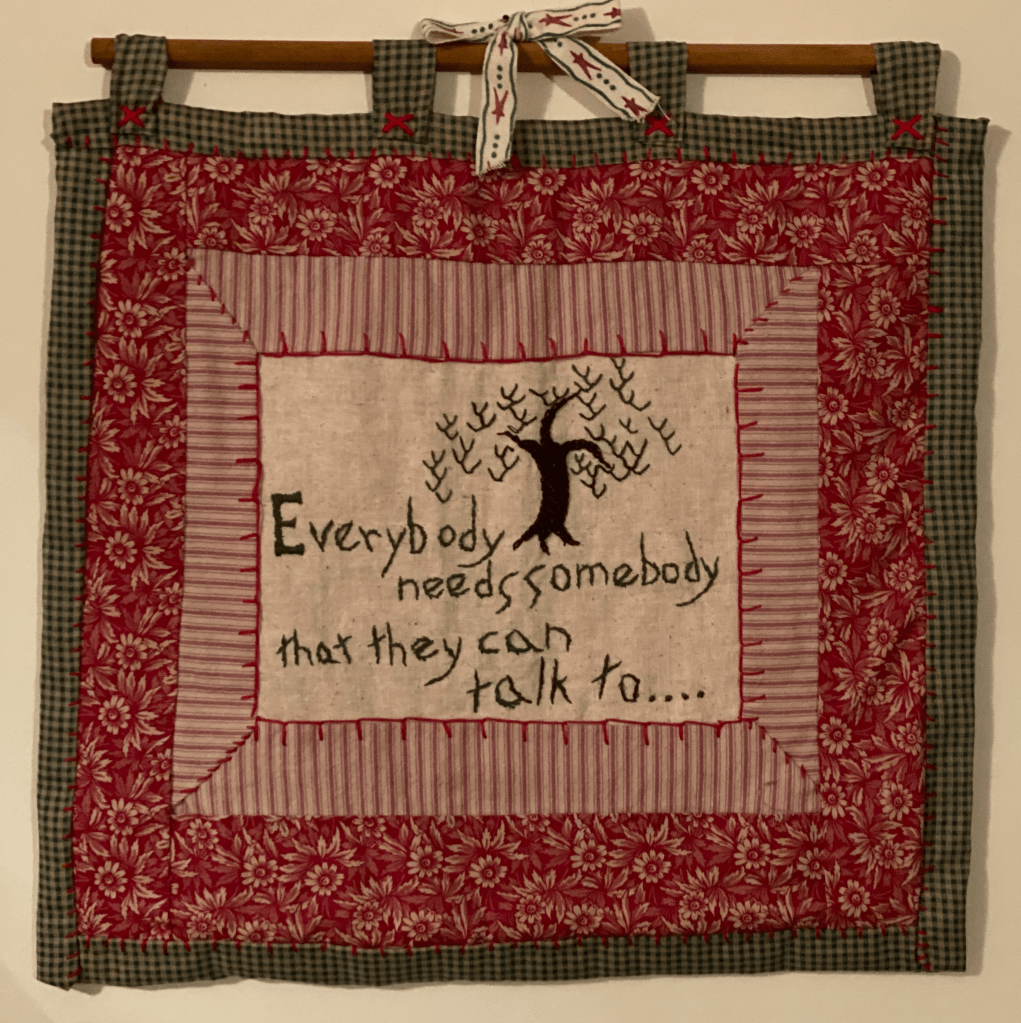

I still slept with my shoes next to the bed AND I taught my boys as much as possible about safety, but the reality was that escape to survive was no longer always an option. I often still “see death everywhere” as my ex-husband used to say, meaning I am one of those safety-conscious folks that drive some folks crazy. Loving children has helped me learn to stay connected rather than seek escape, though, to find trustworthy people, to ask for help and to allow trustworthy others to help me. Over the years there were a number of folks who definitely helped me when I needed it; reminding myself of their support and encouragement has helped me trust that I can find others and allow them to help, too, if necessary. I needed to learn to choose relationships with trustworthy people and to develop alliances, to stop just trying to survive. I needed to open myself to the possibility that there might be more.

Getting older helped: I started wearing more sensible shoes all the time so boots in the car weren’t major safety concerns anymore!

(Photo by Jodi McCullah, 2023. All rights reserved.)

Why, though?

Watching my responses over the years, though, I know, has perhaps caused some folks who know me to think I’m just paranoid or hypersensitive for no good reason. This blog is, in part, an attempt to explain that behavior to those who do not understand. Writing about what has been in that backpack for so long is also for my tribe, for all those other folks who also were awakened in the night by a touch that taught us to be afraid of touch. We share this because we know “just in case” has come before.

I still struggle to say I am proud of all of this. I wish we were still innocents. I wish we did not know what we know. I wish we had different stories to tell. The things we feared, though, were real for us and we did not have the luxury of going through a day without being hypervigilant, without knowing firsthand that sometimes the unthinkable does happen. Sometimes, for some people, the darkness IS dangerous. To survive then, sometimes you do what you gotta do for the time being and, once it’s safer, you can work on growing, healing and learning other ways to take care of yourself. I am grateful, then, for all of you with boots in your car and a pack slung over your shoulder. Maybe it wasn’t always pretty, but we made it.

Because we were prepared, and we escaped, we can live into new possibilities; we can embrace the reality that the frightening place we came from is not all there is out there. (Photo by Jodi McCullah, 2023. All rights reserved.)

As I was writing this, I wondered why the photo below spoke to me and now I realize it’s because what’s around that corner in Venice promises to be beautful and hopeful and exciting. I celebrate all those survival skills, including learning over time that we will find what we need, AND learning to let ourselves ask for and accept help. Good news: there ARE others who do “that.” We are not alone and there are those who love us anyway. Embrace your backpack then or your boots until you don’t need them, then thank them for getting you this far and go see what’s around that next corner! You’ve got this!

Leave a comment