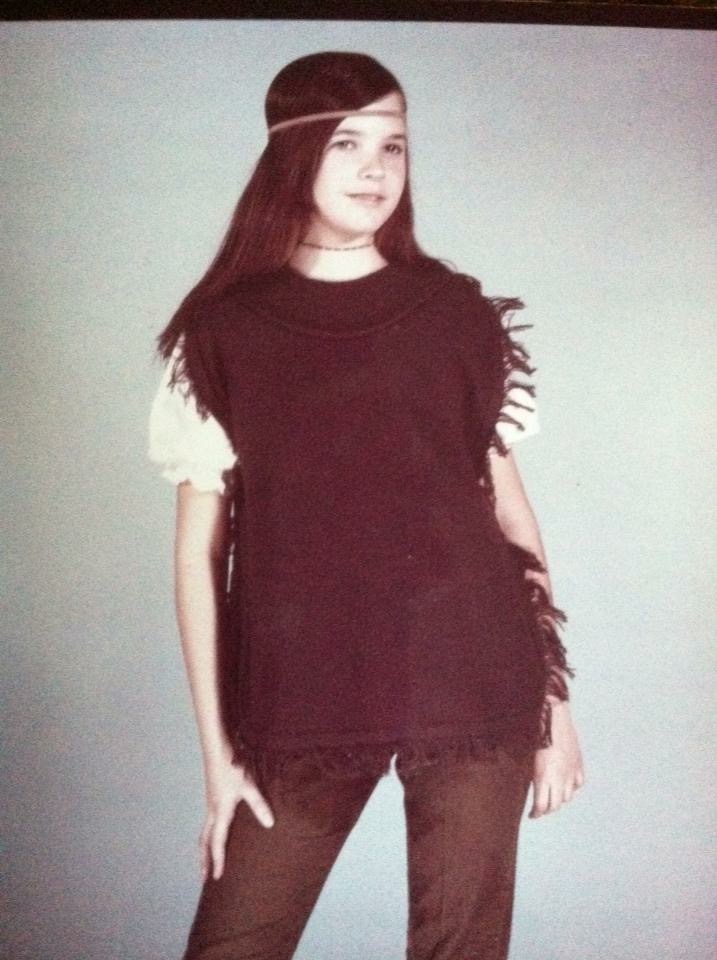

To read part one of this two-part essay, see Speak Up, Young Lady. Be warned, parts of that essay may trigger victims.

Wise ones tell us that we often have to “learn” the same lesson over and over until we get it right. My hint: once you figure out whatever lesson it is you seem doomed to repeat in your life, get on that. Study it. Dissect it. Get it right so you can get it done…or, at least, get good at it.

For me, evidently, one lesson that I have felt doomed to repeat is “Speak up.”

After being fired at age 17 from a fast food restaurant for daring to write a letter to corporate about requiring female workers to wear short skirts (this was in the late 70’s) I found work that fit my college schedule at the county juvenile detention facility. I was thrilled to get the job if only because I was considering a career in social work by that time. Never mind that there was little or no training for the position or that most of my co-workers and I were still teens ourselves; the county simply needed folks willing to work all hours, and willing to be locked into the facility with teens in trouble. College students fit that bill nicely. There were three shifts a day, each eight hours, round the clock, and we all pulled at least one midnight to eight a.m. shift a week. I’m grateful that the teens we supervised were “less criminal and more neglected” teens, picked up mostly for truancy or petty theft or vandalism, but mostly just guilty of being unsupervised. There were three pods of four teens each and our biggest struggle was keeping them from being bored and trying to ignore smartass remarks. I generally worked the 4 p.m. to midnight shift on three of my four shifts, always sharing supervision and feeding and fielding complaints alongside another college student, always a guy since we were locked in every night with boys and girls.

When the dog bites….

Only once did we realize how vulnerable we were, but some training we received came in really handy then and years later for me. During a self-defense training, we learned about getting out of holds and about using weak spots like the instep which is usually vulnerable when someone grabs you from behind. I would years later be grateful for another piece of that training: when we were taught how to react when someone bites you. An unarmed combatant might bite and, while the instinct is to pull away, the best move is to push into the open jaws. That movement will cause the assailant to open their jaw wider and allow you to then pull away. Years later, while out walking in my neighborhood, I would use that with a dog that jumped his fence and lunged for me. I am grateful I saw him coming, though, raised my arm (covered thankfully by a heavy jacket) and pushed back into his jaw as he lunged. He was unable to bite down. We repeated this two more times, him lunging and me pushing back while I yelled for help before another neighbor came out. I’d heard people say time seems to slow in life-threatening moments, and I remember calmly being focussed on my arm going into that dog’s jaw.

It was terrifying.

It was also empowering and would help me in so many ways.

I’d been given one way to stand my ground and I’d seen it work. This would not come in handy until years later, though. At that time, I am grateful to say we had little reason to be afraid of our detainees in the juvenile detention facility.

Again with the troublemaking.

After working there for nearly a year, though, as the juvenile detention facility (which seemed like a lifetime for me at eighteen, by the way) a new worker was hired. Without warning, my schedule was cut in half. It took a week or so to figure out what was happening, but, evidently, the new worker was dating the boss. Remember, this was the seventies. No one even thought of filing complaints then, at least not in Springfield, Missouri. I was angry, but was told at our monthly staff meeting this arrangement would be temporary. By that time, I was living in a tiny apartment. The kitchen was so small I could not open the oven door more than three inches because the refrigerator stood in the way. The bathroom had a claw foot tub with a skylight overhead, though, and a balcony, and I was thrilled to have it, but I would not be able to pay my rent on half a paycheck. Already, I had learned the art of “robbing Peter to pay Paul,” and relied as well on the four meals a week I shared with the detainees at work. This job had been my way out of working fast food; I knew I was far too clumsy to be a server at a restaurant. After nearly a month with my hours cut though, I found it difficult to be cordial when I went to pick up my diminished paycheck and encountered my replacement. I’d thus far received good evaluations, so I was frustrated about having to consider another job. That is perhaps why I figured I had little to lose when the next monthly staff meeting rolled around. After our boss offered updates and training information, he handed out new schedules for the month and, again, I was facing half of my regular paycheck. I raised my hand. My boss called on me. I was standing at the back of the room, aware that others were disgruntled at how things were working out but only two of us had lost significant portions of our paychecks. I simply asked, “What do I have to do to get my hours back?”

My boss looked at me, frowned, and asked me what I meant.

“You know what I mean.” I said, “What do I have to DO to get my hours back?” He definitely knew what I meant. He looked at his girlfriend who was seated next to him up front, then frowned at me. I guessed it was time to start searching for another job. I certainly had no intention of actually sleeping with the jerk. And, while a well-reasoned letter to my boss’s boss might have seemed more professional, as it happened, I got my hours back the next day. Troublemaker. It wasn’t pretty, but it was effective. Noted.

Speaking up, asking people to do the right thing hasn’t always been as successful as I might wish, though. Over the years, the stakes became higher. Sometimes, it did not make me friends with those in charge, and sometimes those in charge used their power in ways that cost me lost opportunities and/or lost income. The best news for me was that often there were others standing with me, and, on occasion, I have been pleasantly surprised by someone speaking up for me.

Sometimes, feeling the need to speak up cost me more than a lost date. While in college, I was invited to apply for a scholarship through a local civic organization to study in France for a year because French was my minor. The opportunity to study abroad would no doubt have opened doors I could not imagine. I wrote my application essay and my resume in French and English, and, of course I listed Leadership opportunities, including some speaking engagements explaining the Equal Rights Amendment in town or on campus. I was told, though, that the scholarship was given to a young man. I would have received it had it not been for my work on women’s issues; evidently the group imagined me sailing across the sea to start riots, maybe even to burn my bra.

I had two ways to see that, I reasoned. I could stop speaking up and go along to get along, but I would have to agree to be like the people who had disappointed me which might lead to me being the reason someone else was disappointed. All these lessons in speaking up followed (or led?) me into teaching and ministry and, while it got some easier, I never really got used to people being angry when I speak up. Now, when I find out, though, that there’ll be consequences or someone is angry, I (eventually) shrug. There are people close to me who I am loathe to upset, but everyone else can just take a number. I might be surprised and disappointed but we’ve come too far now. People just expect it.

Who Knew? My Life Lessons Aren’t Just For Me.

Turns out, learning our life lessons isn’t just for us. What we learn can benefit others. In ministry, I have been called to speak up for my LGBTQ students, those behind bars, wounded soldiers. I was, honestly, as proud as I was distressed to be called “that woman” by some of the folks dealing with wounded warriors at Fort Campbell.

All of my lessons, it turned out, helped in these cases, as did the understanding that the folks who needed someone to stand with them or speak up for them were in far greater pain than any discomfort I felt at speaking up at this point in my life.

Personally, speaking up was easier, in fact, when I was no longer the only one affected. When I had children, I felt keenly the need to protect my boys or anyone else who was vulnerable. My first chance to act on that came when a neighborhood dog began getting out of his fenced-in yard.

Facing the Big Dogs

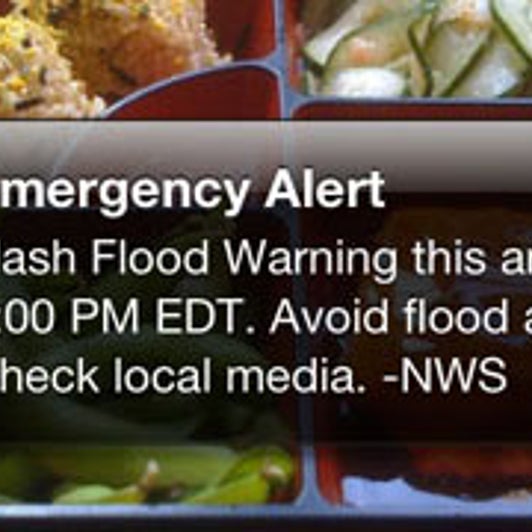

In this case, I thought the “Big Dog” in the small town where my husband and I had settled with our boys was the Collie living on the corner across the street from one of my son’s friends. He was so large he could put his front paws on the shoulders of an adult and look him in the eye. He started demonstrating this on folks in the neighborhood who were strolling around the small downtown area, knocking more than a few of them down. The owner, when informed, usually snarled and slammed the door. When I heard the dog had knocked down the elderly piano teacher around the corner, though, I resolved to call animal control. I discovered though there was only a part time animal control staff in our small town in spite of a growing number of dogs allowed to roam free. I decided to write a letter to the editor -again with the letters, right? – to encourage folks to speak up and perhaps convince our city government to make the animal control agent a full time position. The letter was also an “open letter” to my neighbors with dogs to encourage them to follow the leash law in town and inform them of what was then the local rule at least. According to that rule, a dog owner whose pet bit another person could be made to pay any doctor bills. A dog owner whose dog bit a second time could be sued and, after a third offense, an animal would be put down by the city. I encouraged dog owners to protect both their neighbors and their dogs. Once again, I believed I’d written a well-reasoned letter.

The Big Dogs Bark

The letter was published on a Wednesday. That evening, I received a phone call from the mayor. My anticipation of a good conversation was usurped almost immediately when our illustrious city leader, whom I had never met, began berating me angrily and basically telling me to mind my own business. The big dogs were barking.

I quickly gave up on an actual conversation when it became apparent this was not a dialog. I was honestly surprised that any adult would yell like that at any other adult who wasn’t in their family. He didn’t even know me. I was also confused about why he’d been so rude and aggressive and I began to worry about encountering him in public. I was still pretty unsure what to think about his behavior when, early the next morning, I answered my front door to find the animal control officer in uniform.

You gotta be kidding, I thought.

She was smiling, though, and, after introducing herself, asked if by any chance I’d received a call the night before from the city mayor. Turns out, the mayor had made a habit of nightly drunken calls to people who ticked him off, and this officer often was dispatched by the local sheriff to apologize to the recipients of those calls. No wonder the city couldn’t afford a full time Animal Control officer. We took notice that the understanding was they’d keep up this practice of apologizing for him until the next election. I began to worry about how angry our neighbor with the collie likely was, if he had read the paper.

The Bite

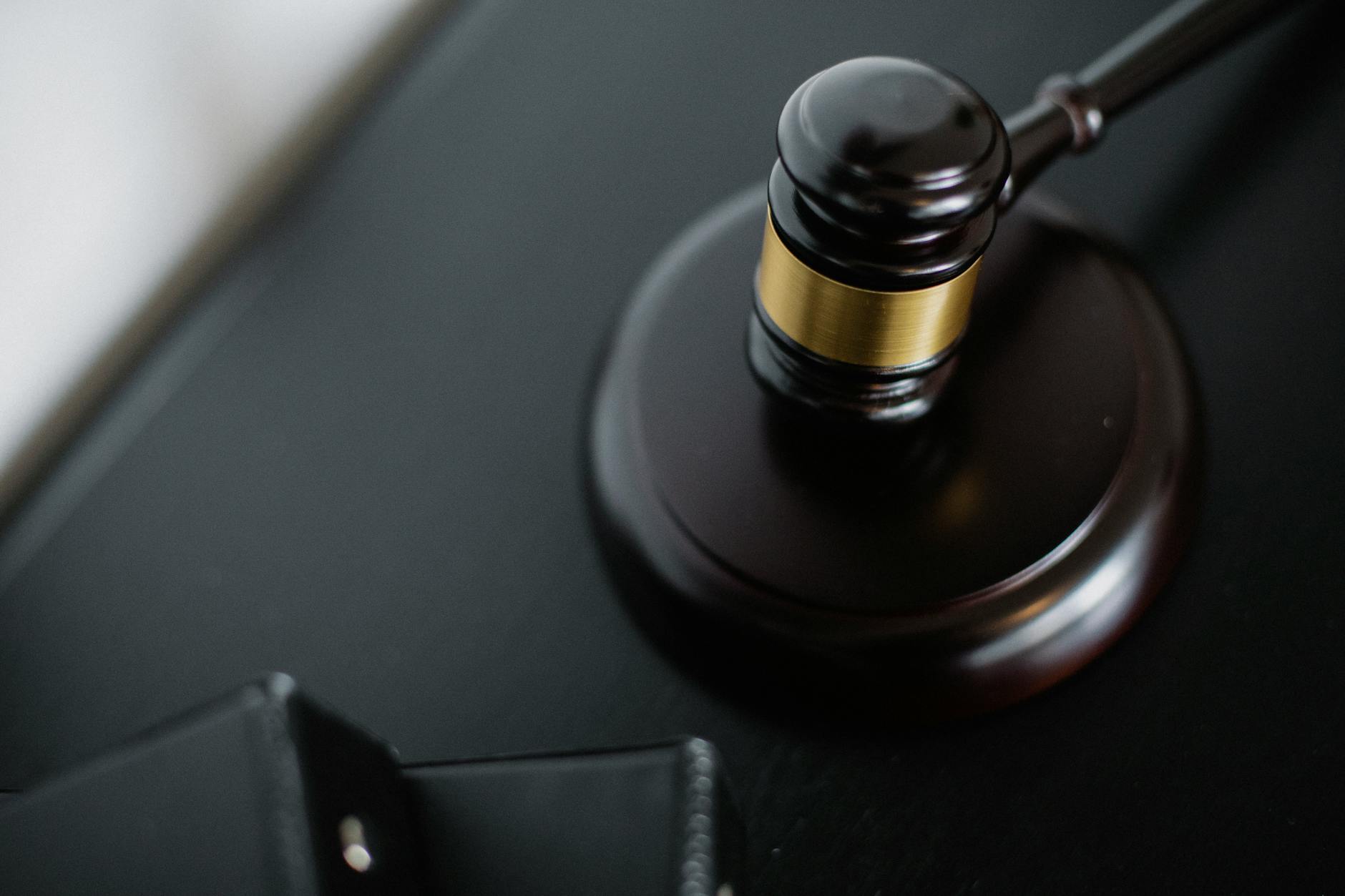

Photo by Tara Winstead on Pexels.com

We got the chance to face him fairly quickly when, a week or two later, I was walking with my eight-year-old to his friend’s house and the collie on the corner lunged out from behind a bush and bit me on the hip before we even knew what was happening. He only lunged once, thank God, and, fortunately, we were just a few feet from the friend’s house. The boy’s mother and I quickly decided I needed to see a doctor. The bite had punctured the skin and drawn blood, but he had not clamped down or torn the flesh. I had not needed to put my juvenile court training into action, I thought, since he only lunged once. The importance of the lesson about standing your ground, though, contained a much wider meaning, I would find out.

The bleeding was minimal but the bruising had already begun and I’d need a tetanus shot. As soon as I finished at our local clinic that day, I walked over to the police department and swore out a warrant. I was driven by the terrifying thought that, had my son been walking on the other side of me that morning, the dog would likely have bitten his face or neck. The thought made the hair on the back of my neck stand up and I knew this was a chance to begin the process to make our neighborhood safer. Though I feared we’d all still have to avoid that part of the neighborhood for a long while, we had put this bully and his dog on notice and try to find some official help.

Amusing detail: the officer who took my information was surprised to discover, through a congenial conversation, that I not only actually loved dogs, we had two big dogs; we just didn’t let them run free. She and her colleagues were under the impression I hated all dogs. She gave me a court date and I left, already afraid and realizing I’d need to warn my boys to watch out in case the neighbor decided to retaliate once he was served with the papers. We stayed close to home for the next few weeks.

When the morning came to face the dog’s owner in court, I will admit I was nauseous and more than a bit afraid not only of facing him but also of how the case would be treated. For all I knew, this dog owner played pool with the local judge. When the judge called us both up to his bench, the neighbor immediately started complaining, “Judge,” he said, “this crazy woman–” but the judge cut him off and asked me for the evidence I had of the bite, which meant both men would be viewing pictures of my butt and hip showing the puncture marks and bruising. A stellar start.

I was beginning to regret the warrant when the judge laid the pictures down, turned to the dog owner and asked, “You drunk, Sir?” My neighbor’s blustery and belligerent response was the judge’s answer.

“You, Sir,” the judge continued, “may or may not be aware that this bite is your dog’s first offense, his first strike.” He held up his hand when my neighbor began to protest.

“You will pay her for her medical bills before you leave. And because you disrespected this court by showing up drunk, your dog now has two strikes against him.” Once again, he held up his hand to stop any protests. “I understand you own some property outside of town; I’d suggest the dog move there. Today. Step back.”

Going through all of that was exhausting and literally gut-wrenching, but I had reached a point where NOT doing anything would have felt far worse.

I’d finally reached a point where NOT speaking up was more painful than swallowing what I needed to say. I did not want to end my life filled with regrets. I’ve hated learning to speak up but I hated not speaking up more.

…where I am today is light years better than where I began, represents so much distance from curling up in the backseat, sure no one would believe me if I spoke up.

This has been my journey and, while speaking up can still be tiring, today I have allies, I have freedom to walk away and I have lots of practice. The need to speak up is mostly easier to face.

This life lesson is no longer the big dog in my emotional neighborhood lunging at me until I fall down.

Maybe you never think twice about speaking up, but I know you have your own challenges, your own life lessons, and I hope you’re moving through them, growing, reaching, finding your freedom. I hope as you reflect on where you’ve been, that you give yourself the benefit of the doubt and that you recognize you likely did the best you could, the best you knew to do, at the time. If nothing else, you survived and learned to do things differently the next time.

My hope for you, then, is this:

May you figure out your life lessons swiftly and early in life.

May you accept help and welcome allies along the way.

May you not reach the end of your life wondering

Where you’d be or

What you’d be doing

If you had stared down your hounds,

If you had pushed back on the jaws that threatened you,

If you had felt strong enough…finally…, become fed up enough, worn out enough to say what you needed to say when you needed to say it.

“Honestly, I wanna see you be brave….”

Sara Bareilles, “Brave,” 2013

Leave a comment