“Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.” Benjamin Franklin

Much of the time when any of us need to draw a line in the sand, as they say, I suspect it is a surprise. I say that because we are often not expecting the person moving aggressively towards us; thus, we are not prepared to mark any line. When we do draw a boundary, when we insist that the next step the person in front of us takes will be too far and we will stand in their way, it can feel jarring and aggressive, like we are the ones being combative. We are simply not prepared to counter aggression or abuse, individually or collectively.

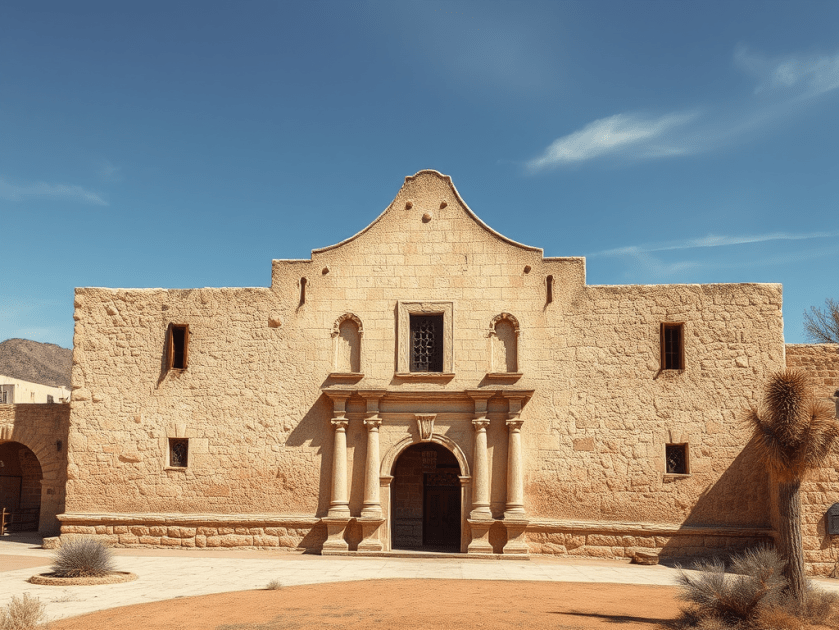

This is somewhat ironic, at least in the United States, though. Remember the Alamo? Legend has it that when Lieutenant-Colonel William “Buck” Travis, Texian Army officer and his fighters faced overwhelming forces at the famed fort, Travis drew a line in the sand with his sword and told his fighters to cross it if they were willing to stay and fight. Nearly all of them did. While that story is possibly more fiction than fact, it is nevertheless the lore many of us were inspired by, taught to emulate, part of the “GIve me liberty or give me death!” understanding of the cost of freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from tyranny. We know what’s right. We know abuse when we see it. We know when someone is trying to frighten us into not fighting for those freedoms. We know and yet we are reticent, loathe to draw our line in the sand, whether personally, as a family or as a community and nation. We want it to all go away. But it won’t.

Years ago, an experience from the first church I served paved the way for an extended family finally to take a stance, to draw their line in the sand to stop the abuse that had been harming women in that family for at least a generation. In this case, what had been a family secret became quite public because the abuser got reckless and over-confident and, in some ways, that arrogance made taking a stand easier for the family.

“Herb” (name changed to protect his victims) wasn’t a regular attendee at the church I served, so my radar was not pinging when I greeted him that Sunday morning. He was a 60-something married man who always dressed in seersucker and bow ties and prided himself still sporting a full head of hair, even if it was graying. I’d brushed off his previous suggestions about how my congregation would like it, he was sure, if I wore more colorful outfits when I stood in the pulpit. I glared at him and walked away when he suggested I unbutton a button or two on my blouse, but nowhere was there any guidance on responding to such behavior from this man whose family members occupied nearly one-third of the pews. I wondered why his wife never attended with him and started avoiding him, thinking he would remember he was talking to the preacher. Turns out, I should have opted for outrage from the beginning. At least I might have been prepared for battle when I walked out of the little white building one Sunday afternoon to see him seated in his big old Buick in the parking lot across the road. I waited for two cars to speed by, then crossed the two-lane blacktop warily, my chest tightening. My arms were full with my Bible, sermon notes, my purse and some funeral home fans that I’d grabbed off the table in the back of the sanctuary. The cardboard fans helped you breathe on the days when the humidity was looking for an excuse to break into a summer shower.

Already sweaty, and looking forward to an afternoon of visiting the shut-ins, I moved cautiously across the road, hoping he would stay in his car. I had been headed to the fellowship hall to lock up before I started the afternoon’s visits. Herb exited his car and was next to me nearly as soon as I stepped off the highway onto the parking lot. I had to stop mid-stride to avoid running into him; I was off-balance as I tried to look behind me before stepping back because that would put me back onto the highway.

Turning towards him, I stumbled to my right just in time to miss him grabbing my arm. I looked at him in confusion as he reached out again and said, “Why don’t we go inside?”

In an uncharacteristic flash of assertiveness, I shoved him with my books. He stumbled back a bit, startled. I darted as quickly as I could around to the passenger side of his car. Did he really just grab at me? Herb started around the side of the car and reached for me again, so I threw my books at the ground near his feet to stop him long enough for me to move around the car until I was back on the driver’s side. I know my hands would have been shaking if I had not been clutching my black leather purse, instinctively wrapping the strap around my hand in case I needed to use it as a weapon.

I would never have expected a man from my church to be bold enough to try to grab me in the church parking lot in broad daylight. That simply was not something I expected. Worse, he acted with such confidence, as if he would face no opposition.

Herb laughed. “Don’t be so silly,” he said, putting one hand on the trunk of the car as he slowly headed back around towards me. He seemed quite amused, at first, that I managed to run around his car—a rather large late model car–but all I could think about was the fact that, thank God, he could not reach across. When he snatched his hand back quickly in pain because the metal was hot enough to sting his hand, I bolted.

He was moving around the car towards me again; I managed to dart into the fellowship hall, drop my purse and the ridiculous fans, and turn the lock on the wooden door. Maybe it was the sound of the door locking–maybe something else–but, apparently something brought Herb back to reality; he “came to himself,” like the prodigal son in Luke, and stopped grinning. Unlike the repentant son who asks forgiveness of the father, though, Herb stood before me, his fist raised, threatening to bust through the window of what seemed suddenly like a very flimsy door. I tried to breathe. Even though he was a member of my church with a large and influential family and now he was angry, I had clearly—finally—drawn a line in the sand.

When he finally got back into his car and drove away, I leaned against the wall and let out a scream, then frantically ran to the other door, grateful to find it was locked. He hadn’t tried opening it anyway. He’d just driven off.

I couldn’t catch my breath.

I gave myself the afternoon off from visiting parishioners. I did not let myself cry until I got home; navigating back roads is difficult enough when you’re watching the rearview mirror for a Buick the whole time.

The next Sunday, and for several Sundays after that, I was greatly relieved that Herb did not return to the church. For months, I would imagine his hand grabbing for me. While I was grateful not to see Herb for a while, I also felt quite alone and indulged in some hefty self-pity as I pondered how large a contingent his family was in our congregation. His wife, for example, was one of several sisters, many of whom attended the church. Herb had married the oldest sister when most of the sisters were still children. At least his wife was not attending our church. A few months later, though, his wife was scheduled for surgery and the prognosis was not good. A pastoral visit to the hospital was in order, if only to console her sisters.

I arrived at the hospital intentionally late. Even after the family was sent to the waiting room before surgery, nursing staff was willing to allow clergy in to pray. I smacked the oversized button to open the doors just in time to go back into the surgical prep area to see her alone. She was still awake and aware enough and thanked me for praying with her. Then I made my way through the winding hallways to the family waiting room.

Nearly every seat was taken by a sister, but I spotted Herb on a chair in the far corner. I took a breath, said a silent prayer, and walked over to him. I leaned down to offer him my hand in greeting but, before I knew it, he was laughing because he’d managed to pull me onto his lap and wrap his arms around me. Even now when I think about how shamelessly he seemed to operate, how little he feared anyone’s disapproval, how brazenly he disregarded the line I had drawn, I want to scream. I’d been pretty damn clear, I thought, that his behavior was not welcome.

I jumped up as quickly as I could and found a chair on the other side of the room, next to one of the sisters. I did not look at anyone for several minutes; I was afraid they would have seen how hot my cheeks were with anger and embarrassment. I was grateful, finally, to look up and notice that sister number two, one of my regular members, was sitting next to me. Voices soft, we chatted quietly about how long the surgery was expected to last. I was grateful she quickly offered to call me when the surgery was over. “We know you have other calls to make, Pastor,” she offered. I thanked her, chose the fastest way out of the room and made it to my car before the tears began.

I drove home discouraged. How could I keep being the pastor at that church? Even if they wanted me to continue, could I keep dealing with this man and his aggressive behavior? I could not shrug it off, and I did not find it amusing, like he did. Worse, I feared other congregation members might also find it amusing.

Everyone in that waiting room had seen Herb pull me onto his lap and me pushing his arms off of me and jumping up but no one had said a word. I’d not received help when I’d spoken to my mentor: “It’s part of the job,” I was told. I did not sleep well that night; I was drafting my letter of resignation from the ministry and imagining the sensation that would ensue within the church once it was made public.

The next morning, I was praying about the letter when sister number two called me, I assumed, to tell me how recovery was going. The conversation was so short I almost didn’t remember it.

“You need to know,” she said quietly but deliberately, “Bobby has spoken to Herb,” she said. “He won’t be bothering you anymore.” She paused. “He won’t be bothering anyone any more.” She paused again. “We’ll see you Sunday.”

Suddenly, I was not alone. One of the other men in the church had stood up to Herb. Sadly, though, slowly, I began to imagine several young women standing next to me with tears in their eyes. I had not considered how many others Herb probably had “bothered” over the years but they were suddenly standing next to me.

All those younger sisters and their daughters would have been easy targets. No one had stood up to him before then. Evidently, no one had even spoken in any voice louder than a whisper about his behavior for decades until that day in the waiting room when he accosted the preacher. The family finally found the line they would not let him cross.

Likely, in the past, the family had hoped Herb’s behavior, something most of them could not even fathom, would have just gone away on its own. Challenging one of the patriarchs of the family had been too painful and even frightening for them to consider. What would they do if he said “she” initiated it? Who might he go after next? What if he suddenly turned the tables and claimed he was a victim? How many of the neighbors might take his side because THEY were already victims and afraid or feared becoming targets?

Because they had never expected to even contemplate such abuse from one of their own, the family could not choose a line.

Because they were afraid to talk to one another about what was going on, no line was drawn.

Because no line was drawn, the abuse continued, unchecked.

Trouble is, this is a common pattern. Whether the abuse is of a person or a group of persons, though, not wanting to talk about it only aids and abets the abuser. Not wanting to talk about what we know is wrong because we are afraid or because it is not our family or because we’re not sure the child maybe “deserved” some punishment or worst of all because we simply don’t want to believe what is happening only emboldens and strengthens the aggressor.

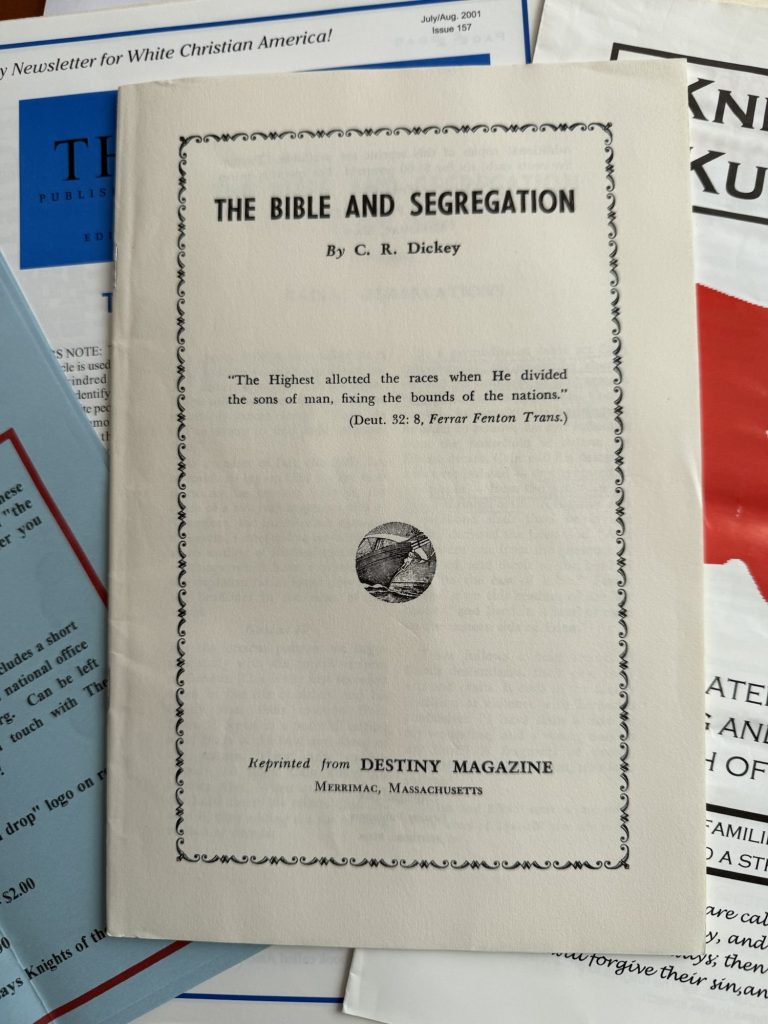

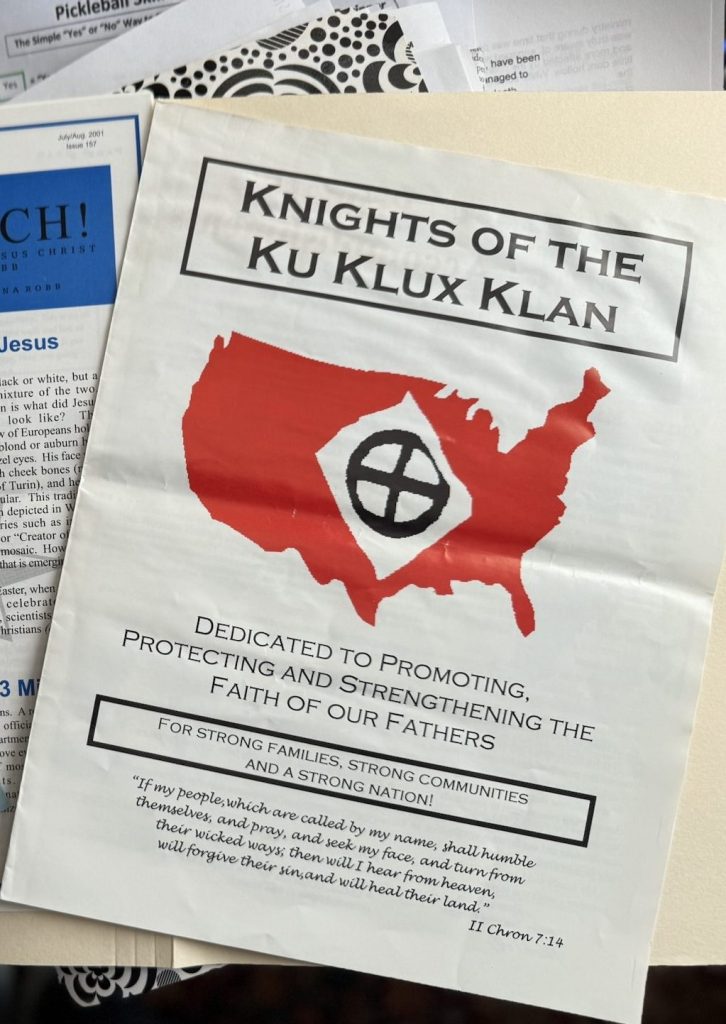

Do not be fooled. These lessons apply to us—to our families and our nation.

We know in our guts how this goes. We know but we are hoping we won’t be asked to draw any lines ourselves.

We wish some people would stop constantly reminding us how more and more boundaries are being crossed every day, how free speech and due process, decency and respect for others are being blatantly, publicly disregarded, then even applauded. We are afraid and tired. Didn’t we move past this decades ago?

Are we waiting for another Colonel Travis to draw the lines for us? Have you admitted you need to think about those now, like it or not?

Are we waiting for another Colonel Travis to draw the lines for us? Have you admitted you need to think about those now, like it or not?

A public school teacher told me today she had decided she would obstruct any immigration authorities who tried to take her students – children – from their classroom. She has admitted to herself what is possible, even as horrific as it sounds, and she decided where to draw her line.

Where is your line?