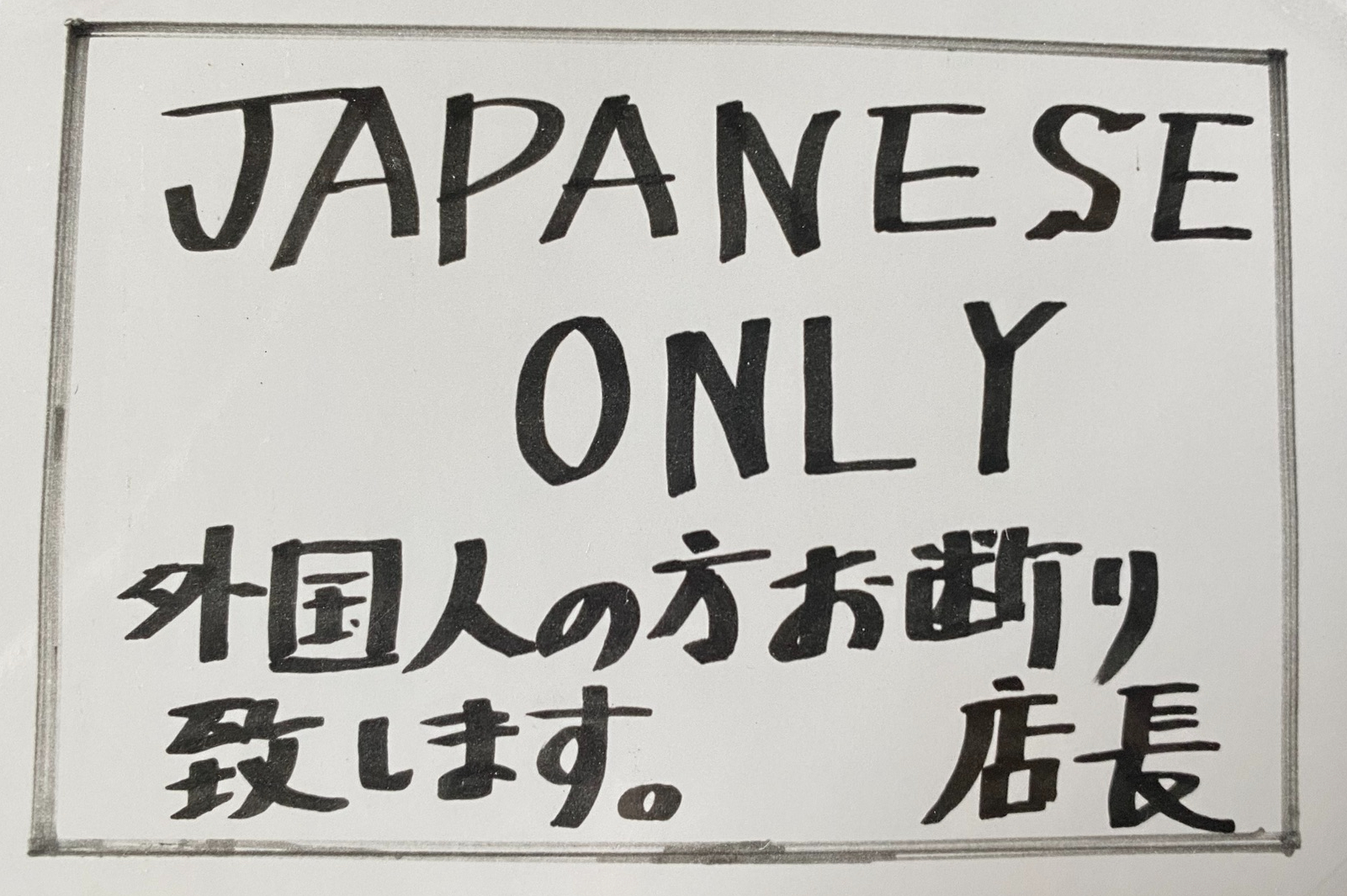

I lived in Japan for three and a half years. Both of my sons were born there. The whole time I lived there, I studied and practiced speaking Japanese. In fact, I had known for a year I’d be moving there so I had started trying to learn the language a full twelve months before ever stepping foot off the plane in Tokyo. My husband and I lived the entire time in an apartment building where we were the only “gaijin,” the only foreigners. In fact, we were often the first foreigners our neighbors had ever met even though there were in fact many foreigners living where we lived – in Himeji, a castle town on the inland sea. This is all to say that we spent our days immersed in Japanese; we learned quickly how to ask for what we needed or just to be able to understand what others were saying because, while most Japanese studied English in school, they learned to read it and write it but not necessarily to speak it. Teaching Japanese to speak the English language was what foreigners like us were hired to do. A common belief we encountered throughout our time there was that gaijins could not learn the Japanese language any more than they could learn to eat sashimi, nori or yakisoba. While we (and most of the gaijin we came to know there) loved the food, we still encountered regularly the declaration that we could not possibly eat, let alone enjoy, the cuisine.

Even funnier was the fact that, more than a few times, we spoke to a neighbor in Japanese, only to be told in Japanese that we were not speaking Japanese.

On a spring morning, I was part of a field trip up into the mountains to eat, of all things, roses prepared in a variety of ways, from batter-dipped and fried to jams. This was with a group of women I to whom I taught English every week for three years. I generally did not speak Japanese to them, but they’d known me long enough to have seen me converse with others who weren’t my students. Standing next to a couple of them, I could hear them talking about me in Japanese. I turned to them and said, in Japanese, “You know I can understand what you are saying, right?” I know I said it correctly because two other students snickered at their friends getting caught and the woman I had addressed turned red. Still, she turned to her confidante and said, “Good thing she can’t understand Japanese.” She could not see how anyone other than a person born Japanese and raised in Japan could possibly speak the language. This was not true for all our neighbors, but it happened, even after we lived next door to them for a couple of years, had worked alongside them, shopped in their stores, enjoyed holiday meals in their homes and gossiped together in the neighborhood’s public bath. Depending on the day, it was either humorous or annoying that a handful of the folks we interacted with regularly simply never could see it though. It went against everything they had been taught and they simply could not imagine, could not see that ever being possible.

They did not have eyes to see.

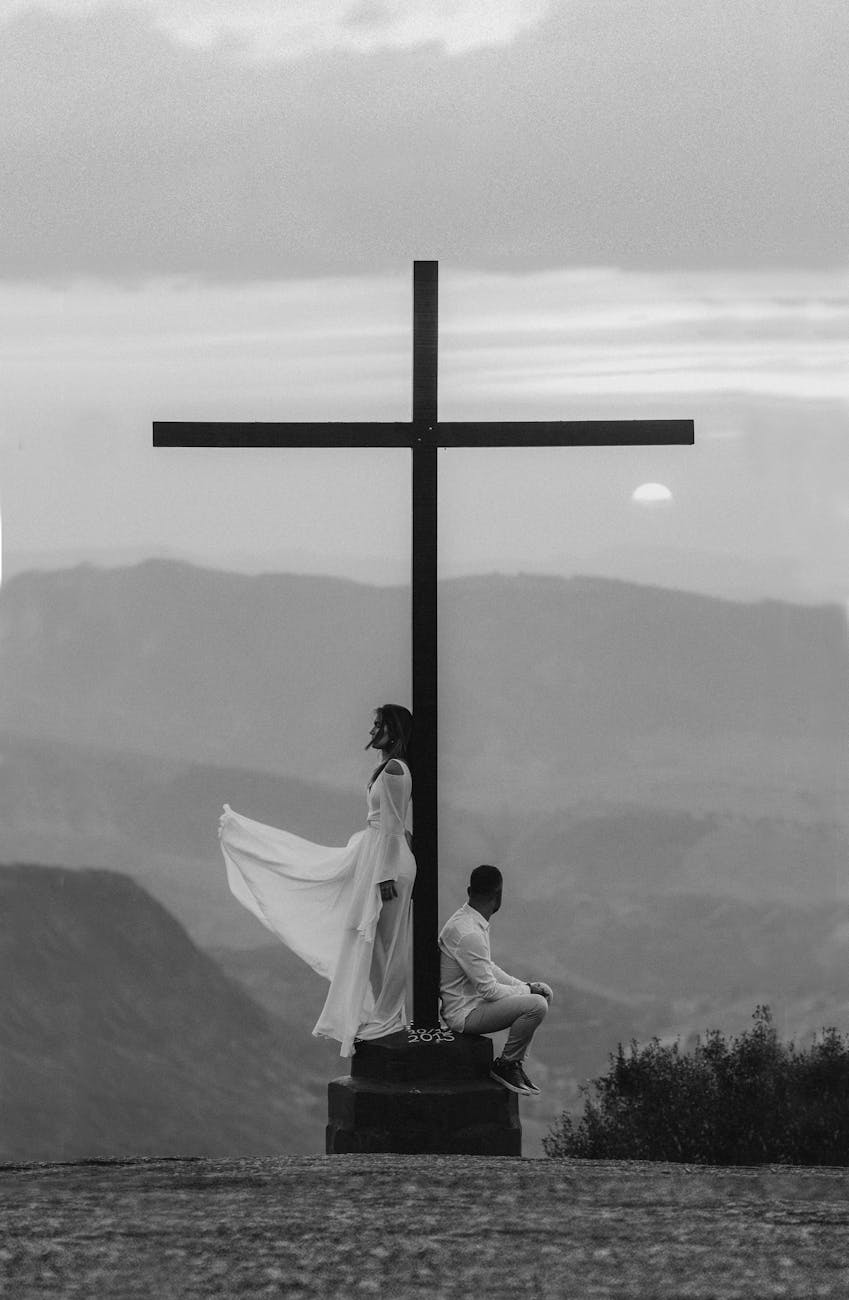

Six days later, Jesus took with him Peter and James and John, and led them up a high mountain apart, by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his clothes became dazzling white, such as no one on earth could bleach them.

And there appeared to them Elijah with Moses, who were talking with Jesus. Then Peter said to Jesus, “Rabbi, it is good for us to be here; let us make three dwellings, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.”

He did not know what to say, for they were terrified.

Then a cloud overshadowed them, and from the cloud there came a voice, “This is my Son, the Beloved; listen to him!”

Suddenly when they looked around, they saw no one with them any more, but only Jesus.

As they were coming down the mountain, he ordered them to tell no one about what they had seen, until after the Son of Man had risen from the dead.

Mark 9:2-9 NRSV

Jesus referred fairly often to us having eyes to see and ears to hear – meaning usually us being willing and able to see something new, a new way to see, because this life, this journey, this faith God offers us through Christ is meant to transform us, to help us to see, hear, understand and ultimately be different. This requires that we enter into that relationship ready and willing each moment to be surprised and to change how we see what is in front of us.

We are in good company if we often find that difficult to do. We simply cannot easily change what we “see.” When I was exploring being called into ministry, I was asked, “Do you see yourself preaching or serving communion?” I simply said, “No.” I had never seen a woman do any of that and could not even imagine it.

Here’s the difficult truth about life in Christ: you cannot enter into that relationship and expect to be unchanged; you cannot experience the transformation that is possible without being willing to see differently, even if that means seeing something that is surprising, or bewildering or that you do not know how to explain.

In Mark 9:2-9, we read, “He changed in front of them.” Transfigured is the word that we have become used to reading here. Transfiguration sounds more holy somehow, more theological than to say simply that he changed. But the Greek word here is where we get metamorphosis — or change.

So what happened on that mountain? Evidently it was something they couldn’t really explain. It remains hard to say what happened, except by repeating the words that we read there. He was transfigured; he was changed before them. What they were used to seeing they no longer saw; and something they had never seen before suddenly appeared to their frightened eyes. We can be sure it was confusing and we can be sure they had choices just like we do: try to forget what they just saw, try to make sense of it or simply move closer because that is where we will be transformed by the renewing of our minds.

“The Gospel of Mark tells us that Peter was so terrified by the transfiguration that he did not know what to say. The Gospel of Matthew reports that Jesus touched the disciples because they were overcome with fear at the transfiguration. And the Gospel of Luke records that the disciples were terrified after they entered the cloud along with Jesus, Moses, and Elijah. All three Gospel accounts record the transfiguration as an experience that was not shared with anyone else for quite some time.”

(Feasting on the Word, Year B, Vol. 1, loc 16361, Kindle Version.)

By the time Mark was writing these Scriptures, he had already witnessed the crucifixion and resurrection. He already knew the end of the story. When our three disciples were on that mountain, though, they did not know what to think and they were just as happy not to have to share the story.

Photo by Jonathan Borba on Pexels.com

Mark wasn’t even on that mountain. He didn’t see what Peter James and John saw. They weren’t supposed to tell so maybe they didn’t. They certainly would not have understood it at the time and if they indeed told anyone, whomever heard it would likely think they’d been drinking strong wine.

Perhaps it would have seemed a lot less crazy AFTER Jesus had come back from the dead to see the disciples. Maybe then they would have had “eyes to see” and could have believed this story and so many others.

He had told them already though. He had told them he’d be raised from the dead. They didn’t believe it apparently.

He’s no pilot…is he?

In “Remembering the Night Two Atomic Bombs Fell—on North Carolina,” a story in National Geographic, we not only learn about a piece of seldom-told history, but also find an example of not having “eyes to see.”

Seems that sixty years ago, at the height of the Cold War, a B-52 bomber from Seymore Johnson Air Base, near Goldsboro, North Carolina, was carrying two 3.8-megaton thermonuclear atomic bombs when the plane disintegrated, killing four of the eight crew members. The plane crashed in a fiery mess, but not before jettisoning the two bombs, what the Air Force would call “Broken Arrows.” Somehow the bombs both landed without exploding or this event would be a whole lot more well-known than it is.

(All quotes from this story are from National Geographic, Bill Newcott, 1/23/21, told by eye-witnesses and Joel Dobson, author of a book on the subject (The Goldsboro Broken Arrow.) https://apple.news/AZQ4ng5GNQQ65TcanqBG4yg.)

What the people of Goldsboro did not know then was that their little air base had “quietly become one of several U.S. airfields selected for Operation Chrome Dome, a Cold War doomsday program that kept multiple B-52 bombers in the air throughout the Northern Hemisphere 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Each plane carried two atomic bombs.”

“A few weeks before, the Air Force and the plane’s builder, Boeing, had realized that a recent modification—fitting the B-52’s wings with fuel bladders—could cause the wings to tear off. Tulloch’s plane was scheduled for a re-fit to resolve the problem, but it would come too late.” The plane started rolling and tearing apart and [The pilot] knew his plane was doomed, so he hit the “bail out” alarm.”

“Of the eight airmen aboard the B-52, six sat in ejection seats. Adam Mattocks, the third pilot, was assigned a regular jump seat in the cockpit. The youngest man on board, 27-year-old Mattocks was also an Air Force rarity: an African-American jet fighter pilot, reassigned to B-52 duty as Operation Chrome Dome got into full swing. At this moment, it looked like that chance assignment would be his death warrant.”

Mattocks’ only chance was to somehow pull himself through a cockpit window after the other two pilots had ejected.

“He was a very religious man, and telling the story later, said he looked around and said, ‘Well, God, if it’s my time, so be it. But here goes.’”

“It was a surreal moment. The B-52’s forward speed was nearly zero, but the plane had not yet started falling. It was as if Mattocks and the plane were, for a moment, suspended in midair. He seized on that moment to hurl himself into the abyss, leaping as far from the B-52 as he could. He pulled his parachute ripcord. At first it didn’t deploy, perhaps because his air speed was so low. But as he began falling in earnest, the welcome sight of an air-filled canopy billowed in the night sky above him.

“Mattocks prayed, ‘Thank you, God!’”

“Then the plane exploded in midair and collapsed his chute.”

“Now Mattocks was just another piece of falling debris from the disintegrating B-52. Somehow, a stream of air slipped into the fluttering chute and it re-inflated. Mattocks was once more floating toward Earth. Looking up at that gently bobbing chute, Mattocks again whispered, ‘Thank you, God!’”

“Then he looked down. He was heading straight for the burning wreckage of the B-52.”

“Well, Lord,” he said out loud, “if this is the way it’s going to end, so be it.” Then a gust of wind, or perhaps an updraft from the flames below, nudged him to the south. Mattocks landed, unhurt, away from the main crash site.”

“After one last murmur of thanks, Mattocks headed for a nearby farmhouse and hitched a ride back to the Air Force base. Standing at the front gate in a tattered flight suit, still holding his bundled parachute in his arms, Mattocks told the guards he had just bailed from a crashing B-52.”

“Faced with a disheveled African-American man cradling a parachute and telling a cockamamie story like that,

the sentries did exactly what you might expect a pair of guards in 1961 rural North Carolina to do:

They arrested Mattocks for stealing a parachute.”

Nothing else made sense to them – they could see no other possible explanation. They did not have eyes to see.

“Of the eight airmen aboard the B-52, five ejected—one of whom didn’t survive the landing—one failed to eject, and another, in a jump seat similar to Mattocks, died in the crash. To this day, Adam Columbus Mattocks—who died in 2018—remains the only aviator to bail out of a B-52 cockpit without an ejector seat and survive.”

The guards that night could not see it though, could not see how this man could be the pilot of a US bomber.

What can WE not see? What can we not accept because we cannot explain it, cannot see it, cannot imagine it being right?

We do not do this alone. We stand together in open-mouthed wonder at the fullness of the Christ we worship; together we marvel at something we didn’t think could ever be, things we didn’t think we could ever see. The Good News then is that we don’t have to explain everything, only to follow and be willing to follow somewhere that perhaps we can’t explain and can’t understand, trusting the promise that we will have eyes to see, and we will be transformed, if we will follow.

Leave a comment