I’ve been thinking of late that I need to write a book where every entry begins with, “I Am Not A Nice Person.”

It seems I frequently wake up thinking of starting an entry with that statement, followed by lots of annoying thoughts that have been buzzing about my head like nasty little kamikaze planes. I wake up certain that, if anyone heard all the complaining and frustrations clogging my poor little brain, they’d agree wholeheartedly that I’m not so nice. Sadly, much of my writing through the years has been nothing more than me complaining. What I have figured out, though, (through writing, thank you) is that dumping all those complaints onto paper for all these years has done me – and everyone around me – some good.

Honestly, I write because I too often wake up wanting to scream.

So, perhaps more accurately: a blog entry today should read simply, “Gotta write.” It will do me (and the people around me) some good.

Seriously, if you know me, you should count yourself fortunate that most of my furiously scribbled pages and pages have been purges no one else will ever read. I’ve spent the majority of my writing time getting my frustrations or anger or complaints off my chest, out of my mouth and thus, (mostly) out of the earshot of those around me. My husband has learned that my being in a bad mood and complaining is quite often a sign I am not writing.

So maybe, I thought, instead, a blog entry today should read simply, “Gotta write.” It could do you (and the people around you) some good. Perhaps you – or someone you work or live with – is simply a frustrated writer.

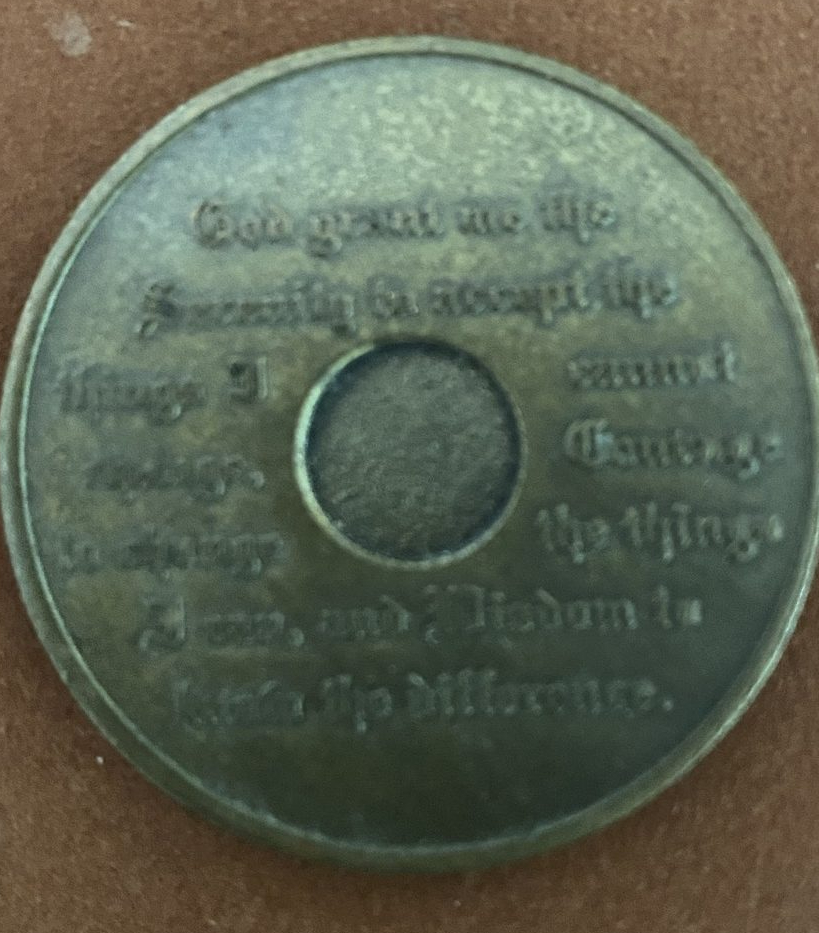

Writing is simply therapeutic.

Let’s be clear, though, there’s being a writer and there’s being an author.

Writing for therapy isn’t the same as writing because you might want to share your stories. The first is for your eyes only, a way to get all those thoughts and frustrations and even giggles out of your head to make room for some clarity or joy or discovery or a story to share. The second is a craft, i.e., what you do to the rare few of those rants and raves that warrant a second glance. Some will be worth a second look and perhaps the effort to fashion them into something another person might be keen to read or gain a personal benefit from the effort. This doesn’t matter as much because there’s honestly great overlap there.

Lots of people around me tell me (now that I’ve published a book and they’ve read it, thank you) they also have stories they love to share over meals, on the bus or while waiting in line, but are stopped by the thought of sitting and typing or writing them out. Simple enough, I tell them, use those easily available programs or apps that allow you to dictate, then go back and edit. For myself, I truly prefer the feel of graphite on paper, I explain, but that means I have to then go back and type up what I’ve written. So I have been using a Remarkable, an electronic pad that lets me use what genuinely feels like a pencil, then converts my scribbles to text. “Oh, my writing is too sloppy,” is the excuse most folks offer for why that method won’t work for them. I write quickly and in cursive on mine and, yes, some editing is necessary but the system works pretty darn well and I’m nearly finished with a second memoir written on the tablet.

“I can’t seem to find the time,” I hear. Years ago, though, I read about how helpful it could be for writers to simply buy some cheap spiral bound notebooks and every morning with coffee just scribble three pages. There’s a book and workshops and support for folks who want to use this method and I recommend them, but the gist is simply to write. You can start every morning with “I am so mad at….” or “I cannot understand….” or “I remember….” Just write is the idea. Write the first sentence over and over if you need but fill up three pages. You may not ever look at those pages again but your purpose is not to write the great American novel. It is simply to write. To get what’s in your head on paper. To grease the wheels. To make it easier and easier and more and more addictive to write than to not write. And to get whatever is annoying you off your chest.

This follows the discipline suggested by the writer and teacher Natalie Goldberg of writing three pages a day- scribbling, really, without allowing my brain to edit while I dump what’s on my mind. “Writing Down the Bones,” by Natalie Goldberg .(https://nataliegoldberg.com/books/writing-down-the-bones/.)

Goldberg teaches about getting those “first thoughts” on paper by keeping your hand moving and not letting yourself have time to edit, not stopping to criticize yourself or correct your feelings, simply to get those thoughts out of my head. The process is similar to keeping the wheels of a wagon greased. Whether you write for yourself or for others, this or some kind of discipline that involves putting pencil or pen to paper is, in my opinion, the place to start. Goldberg also points out the act of writing regularly teaches us to listen to ourselves, can help us overcome our doubts and affirms for each of us the value of our lives.

Often what I end up with after scribbling as quickly as possible in a cheap notebook amounts to nothing more than a jumble of frustrations but that allows me to get it out of my system. That way, I don’t bore others around me with complaint after complaint and I don’t repeat myself all day because, I suppose, my subconscious knows it’s out of me. This is similar to writing lists for myself. I can go to sleep at night without worrying about what I need to do tomorrow because I’ve deposited those tasks onto a written list that’ll be waiting for me by the side of the bed when the alarm rings.

I also know where I can find it if I need to complain more. Again with the complaining. In all seriousness, writing out what I think helps me know what I think, discover how I feel, remember better, understand myself better and even uncover ideas about how to actually do something about what makes me so angry and frustrated, something more than simply grousing.

Whatever helps you write helps you write.

I read a quote some years ago declaring that the best discipline for any writer is to read. Gonna have to disagree. I respectfully disagree. The best discipline for a writer is to write. If you want to be an author, there are further steps. Find a continuing education course on the craft of writing or poetry or songs or memoirs. Next best: get your butt into a writer’s group. Writing to be an author is after all a craft and the steps to any kind of writing you want to publish are many. There is nothing to be brought to the crafter in you, though, if you don’t actually write. I don’t manage three pages everyday but I scribble enough to provide fodder for all kinds of stories if I want to use them.

Seriously, writing is simply therapeutic.

More critically, writing saves my friendships, my marriage and my sanity and, on occasion, helps me figure out how to help.

Last week, my furiously scrawling carried me back to those “Weekly Readers,” those newspapers designed for school-children. You remember? Where we learned about preventing forest fires, about how littering made others so sad, especially that American Indian chief with one single tear rolling down his cheek? Remember trying to wait patiently as the copies were passed out. Remember how we eagerly but gingerly turned each page to learn about how seatbelts saved lives, about the Civil Rights Movement or Rachel Carson or the value of community service?

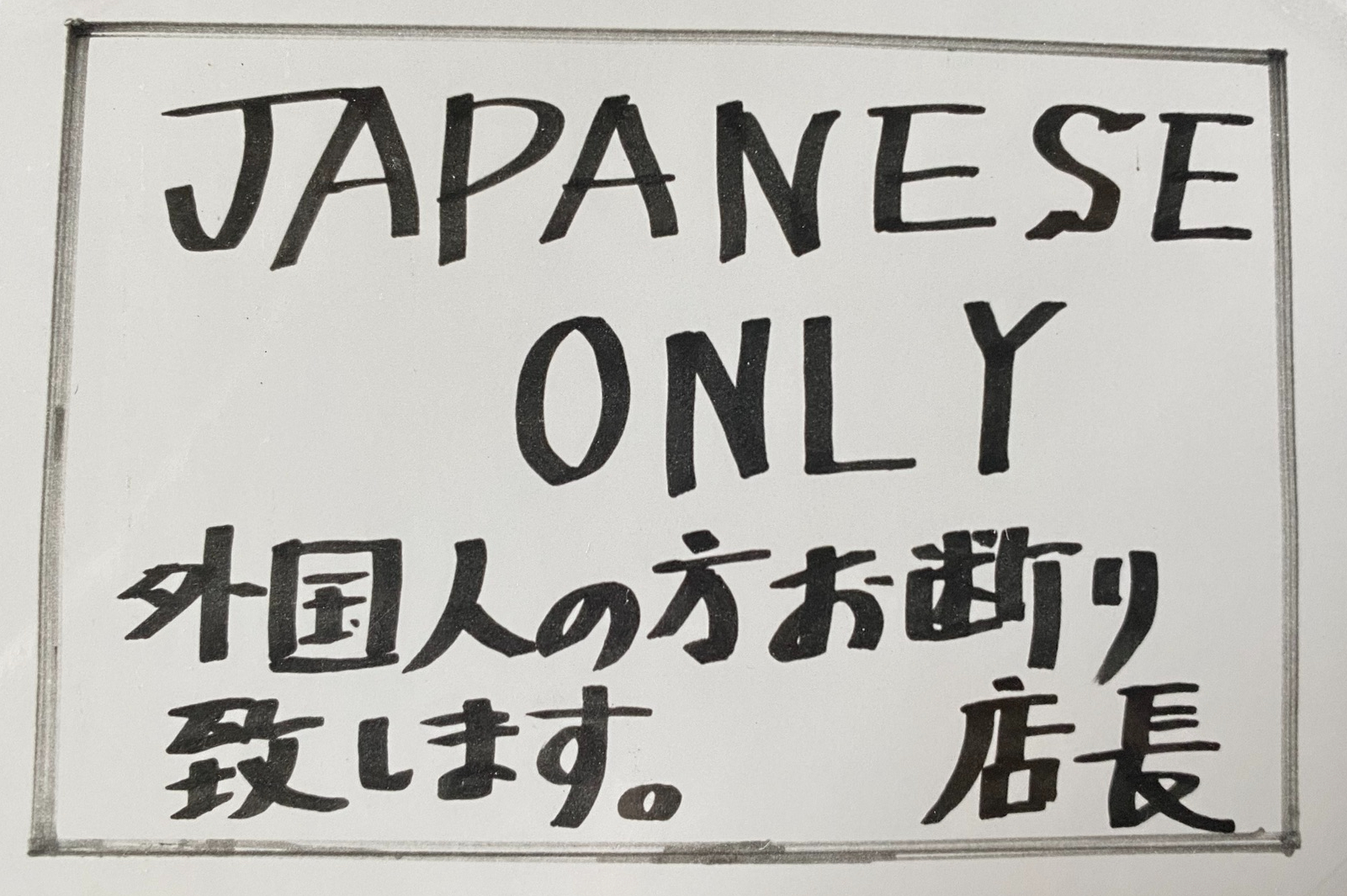

Those little newspapers were both welcome departures from math problems and verbs and adverbs AND they presented as gentle guides to create better neighbors and friends. Through them, we all became more aware of poverty, child labor, the dangers of tobacco smoking, and racism, among so many other issues.

Why do I find myself remembering and writing about Weekly Readers? You know why. Because so much of the progress we were inspired to help bring about over the past 50 years has simply been erased or rolled back at a terrifying speed.

Good God, if we keep going, the next logical outcome will be another Executive Order banning handicap accessible restrooms because they discriminate against the “able-bodied.”

You remember what things were like back then, before so many of the “woke” ideas helped make our world a better place, don’t you? My mother could not get a job, a bank account or rent an apartment without her husband’s or her father’s permission, for just one example. Um, not willing to go back.

Today, those newspapers would likely be considered anti-American. How dare they, for example, teach us about global warming, slavery or trying to normalize women and minorities in leadership, business or science roles?

The power of the Weekly Readers was they helped turn us into informed and empathic citizens, people who cared about one another and who recognized that we needed one another to be the best we each could be.

I am wondering now, if there isn’t some way to bring those back and deliver them right to the children at their homes? How subversive is that? Maybe Dolly would help. That’s the kind of idea that surfaces when I write. I want to know what comes to mind for you? Share. Let’s collaborate.

For now, next time you – or someone you know – thinks all you do is complain, go to the corner store and buy a cheap notebook. Choose a pen or pencil that feels good in your grip and start writing. Every morning. Only, make yourself a deal. Just write and know that most of what you write for a while, maybe for a long while, will just lay there scrawled in cheap notebooks. Don’t expect great things. Just write about all the things that you can’t stand – you may never get it all out of your system but you and everyone around you will thank you for leaving it on the page. You may not ever want to use any of that but, then again, you might.

Maybe you will be the one who come up with some ideas about how we can stop what appears to be a national temper tantrum.

Ever notice how our leader always SCREAMS his posts on social media? What if we could get him to write BEFORE he shared?

Seriously, doesn’t it lately feel like so many people are simply pouting because they don’t want to share anymore or be nice or take turns? Faithfully writing out my three pages has helped me share with others what I think without screaming at them.

What I realized years ago is that writing is how to scream in a socially acceptable way.

I too often wake up needing to express my frustrations with the world, perhaps now more than ever. So, I am convinced the world is a better place because I leave most of it on the page. Less anger is spewed, less frustration gets passed along, less whining and complaining and criticism.

I DO think more about how to take action, though, and I’m a bit clearer on what and why. I remain certain that if people in my life knew how much I spewed, well, they’d be sure I wasn’t such a nice person. Because I write, though, at least some people like me most of the time. And occasionally, I figure out something to say that is helpful, useful, perhaps even wise. Through writing, I am learning that my superpower may be that I see and feel and cannot pretend the emperor is dressed. That’s what writing does. Honestly, it’s subversive.

And that’s what so many of us need right now to help us keep our sanity.

Now more than ever. I saw a meme last week that showed a woman holding up a sign that read, “We should all receive Oscars for acting like everything is okay.”

Every damn thing is not okay, let me assure you, and, depending upon where you live and who populates your family, maybe it never has been. So start writing about it. Get the screaming out in a way that doesn’t hurt anyone else. Figure out what you think. Let the rest of us know you’re with us, that you see, too, and especially, share any ideas. I’m seriously considering a Weekly Reader reboot and I’m gonna ask Dolly to help.

Leave a comment