All happy families are alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina, 1878

People who are happy are not paying attention. And probably stupid.

Me, 2005 in a seminary class (Yeah, I’m not proud of that.)

We all learn lessons growing up. Some friends tell me today about learning how to hold their own in a fist fight or how to plait hair or how to make a decent pie crust. Those tend to be the friends whose families do not match the same clinical dysfunction criteria mine did. Warning: some of this post might be triggering for readers. Take care of yourself, please.

If you looked at my family tree, you’d see the roots are severed. I am grateful, though, that the tree trunk has survived and flowered nonetheless. While I have been cut off from my family of origin for more than a decade, I am so very grateful for my husband, my sons, my granddaughter and my husband’s large extended family. I do not lack for people who care about me; what I was not able to produce for some time, though, was a witness to much of my life before the break with my parents, siblings and extended family. I lacked someone who could pick me out of the class photo (usually one of the taller kids on the back row). Missing was anyone who knew I didn’t usually eat my birthday cake, only the icing, or that I read every biography and autobiography in my elementary school library and that I grieved when I finished books because, for the few hours when I was reading, I was able to wander around in another space and time – one that was not mine. I lacked anyone who could give a witness to any of the reasons why I thought for so long that happy people were not paying attention to the pain in life.

Can I get a witness?

When asked to describe my family as I was growing up, I’d explain: you could be lying on the braided rug in the living room, devastated, distraught, lost, and sobbing, and every member of my family would step around you at best. Or, at worst, they would chastize you for your selfishness: just look how you are upsetting everyone else by your pain! Not only did we NOT hold onto one another in times of crisis or pain, we denied one another’s right to be in pain. “How long you gonna be a victim?” was what was asked of me by a family member after she’d heard I was in counseling for being assaulted as a teen. I was in my early twenties. I had just remembered the assault that I had blocked out of my consciousness for several years because it was just too painful to remember. I had only just begun counseling and I felt her rebuke keenly. There was evidently no place in our family for that. She, a woman thirty years older and presumably three decades wiser, could not cotton my taking any time to understand and come to terms with what had happened to me. Today, thanks to counselors and learning about trauma, I would be able to put my hand on her arm and reassure her that she would never need to listen to my struggles. I would also explain to her that recovering from trauma requires some reflection, though, and some help understanding what happened and more than a little work to heal. I would assure her I certainly did my part to finish that work – to come home from the journey someone else started me on. I would also plan to be there for her if she ever felt like she could share her own pain.

Sadly, family breaks are more common in my family than not, though, so, when the relationship with my mother’s family was severed, our entire nuclear family was already split from Dad’s people. As an adult, I started a genealogical search only to find I had a great-grandmother living about an hour away by car until I was a teen whom I hadn’t known existed. I asked my parents at the time and was told “We didn’t like her very much.” Later, I found an old family photo with one woman’s face scratched out completely (and she had been sitting next to her twin brother in the photo!). What do you have to do, for goodness, to get completely scratched out of existence? Evidently, severing ties, splitting up was the response of choice for my people.

In the past few years, though, through the magic of the internet, I have been able to reunite with some folks from my childhood. While for some, that can be a hilarious trip down a bumpy old memory lane, for others of us, restablishing connections can be healing and grounding. As a sixty-something woman estranged from her entire family of birth for more than a decade, finding these old friends had been spurred by the need to find folks who could vouch for my previous life.

This, then, is a post about my friends from childhood and teen years reconnecting and discovering how little we knew about each other in spite of how close we thought we were.

I was always jealous of those who stayed close to their friends long after school; I believe now that most of my friendships were more akin to life boats in the midst of stormy seas. Survival was the goal, and perhaps we knew instinctively that two or three strands of rope were stronger than one, so we held onto one another. Once we found ourselves in new oceans, though, we grabbed onto new, different life connections, and let go of the old ones, not because we were inconsiderate or uncaring but out of necessity. No one had time or energy to look back; survival was the priority.

Puzzle Pieces

Trauma, though, can leave fragmented memories. One definition of trauma is that we remember all too well what we cannot forget but struggle to remember all the pieces in between – the rest of the story. I have long been embarrassed at being unable to remember large chunks of my life because I didn’t realize how large was the shadow of trauma and how it can so deeply darken the rest of our lives. The details, so many pieces, seem lost, scattered, in my case, all over the world like a favorite nesting toy. Through more than seventeen moves before I was old enough to leave home, curiously, I have somehow held onto most of a wooden nesting toy from Pakistan, where we lived when I was a child (stories for another post.) Some of the pieces are missing and others have been glued back together; today they serve as an apt metaphor for the struggle to repair and hold together memories of traumatic childhoods.

Comparing Notes

Once we reconnected, my friends and I began comparing notes. One childhood friend thought I was an only child though I have two siblings and we are all just a year apart in age. One of us had grown up with an abusive father. She married four times before she got help and stopped getting herself into abusive relationships. Another lived with an older brother who we now realize was a sociopath. She had found not words for when, as a seven-year-old, he had cheated, stole and tried to be sexual with her. Weren’t there rules about that?

That no adult saw all of this meant it continued, and by the time she was eight, he had run her over with a bike causing her to need stitches and hit her in the head with cutting board causing more stitches, and routinely touched her inappropriately. “Just a rowdy boy, right? Just a kid who doesn’t like to lose, wasn’t he? He’ll grow out of that, we are certain.” She grew up searching for an adult – any adult – around her to be the adult and a witness to what she was experiencing. She knows now that her brother simply passed along his own pain.

Healing began when a counselor said, “You were not imagining this. You are hurt, angry because you were betrayed by parents who were supposed to take are of you. You have those feelings because you have a brain and eyes to see. You doubted yourself and what you saw and experienced because you were raised by parents who were overwhelmed by their own pain and shame and guilt; they had nothing to offer you for yours.” A teen aged girl, she wanted her mother to teach her to curl her hair; instead, she watched her mother threaten to cut herself.

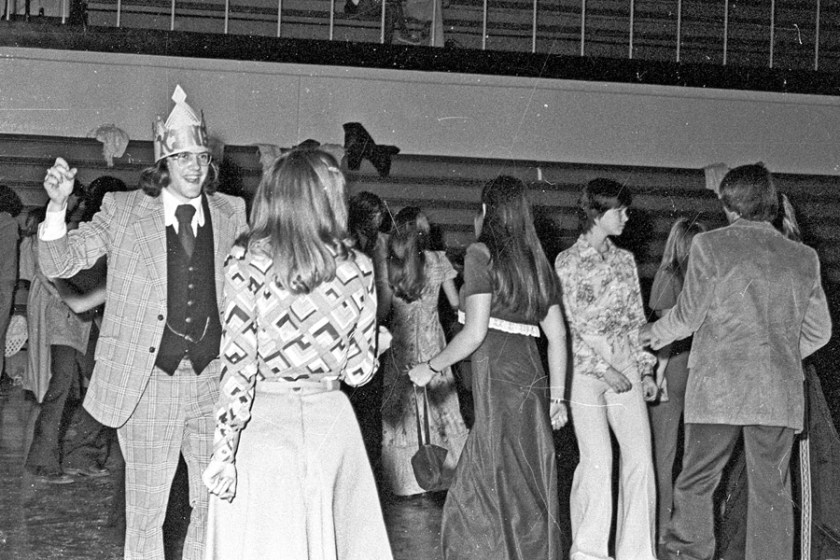

While it was happening, though, none of us “knew.” As teens in the late 60’s and early 70’s, we braved new styles together: we traded bell bottoms and hip huggers and together we tried cheap strawberry wine behind the concession stand at the drive-in movies, but we never shared about home. We didn’t “know” even though we saw each other every day at school, ate lunches together, joined cheer club together, and moved around in a pack as if we were attached to each other by velcro. We were all taken aback when we collectively realized that none of us, though fast friends throughout junior high and high school, had ever visited the others’ homes. No sleepovers. No parties together. None of us had ever even met the others’ parents. We didn’t know why, but we all somehow understood one another. Somehow we saw in each other kindred, if broken, spirits, and we found respite in our time together.

We didn’t know how much we didn’t know.

Today, as the three of us somewhat gingerly share our memories, fragments and misunderstandings are beginning to make sense to us. Counselors and social scientists tell us now that we compartmentalised our lives, partly out of shame, partly to protect the others. We never spoke of life at home or after school; we kept those separate. In our defense, we didn’t often know what was going on in our homes wasn’t going on in everyone’s homes. Part of the power of dysfunction is that it simply seems like “that’s how it’s done, so why are you whining?” Or worse, we feared that the pain and chaos and constant crisis of our homes was somehow our own faults and if we’d only be better daughters….

Dysfunction, though, happens in shadows and darkness and thrives on secrecy.

We know now that each of us fought to get out of that darkness once we left those homes and we celebrate our individual efforts to keep our own lives in the light.

“The light came into the world, and people loved darkness more than the light, for their actions are evil. All who do wicked things hate the light for fear their actions will be exposed to the light.”

John 3:19b-20 CEB

What do we do differently?

We learned to encourage the children in our lives because each of us could remember at least one person who had encouraged us. Never underestimate the power of encouraging a child or teen; you may well be the only encouragement they receive.

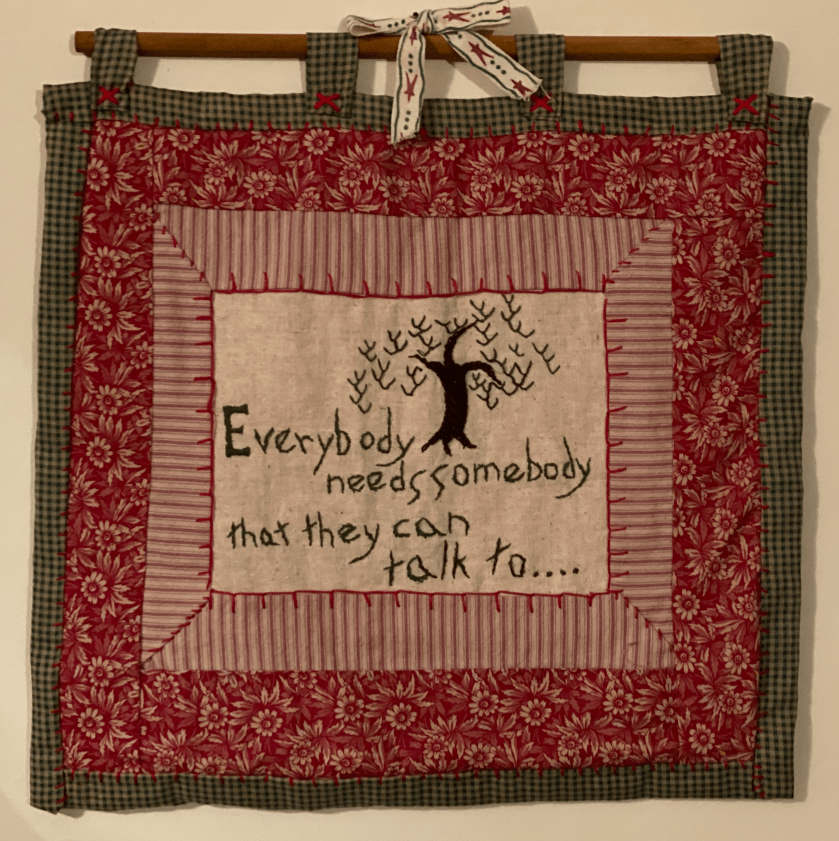

We refuse to keep secrets. We ask tougher questions. When we see someone sobbing, we approach them gently and ask what we can do. If they don’t know or can’t answer, we sit down with them and wait until they are calmer. We hold sacred space for our own pain and for theirs.

One of the three of us refuses, even when facing family verbal and emotional abuse herself, to walk away completely herself because of a child in the extended family; she doesn’t want the child to feel alone. She knows how important it is for someone to say, “I see you. I see what happened. I see how confusing it must be.”

One of us worked hard to figure out why she kept getting herself into abusive relationships over the years and now she is able to choose healthier relationships and she doesn’t need to hide that relationship from us.

None of our parents paid any attention to where we went or with whom, so we each had resolved to offer our children a healthier childhood, making sure their friends knew us and we knew the parents of their friends.

We also grieve those who did not make it; each of us has family members still hurting, still in the darkness, unable for a variety of reasons to find their way out. We are grateful and we do not take our own growth for granted.

Okay, sharing isn’t always “nice,” but it IS healing.

The tagline on this blog is “Sharing is nice.” That is my witness. Sharing is difficult. Sharing is scary. Sharing is necessary. Sharing is essential. Sharing is healing. Sharing is powerful.

The good news is that we all found healing because we shared. There’s help out there and hope and healing and lots of folks who are called to listen and trained to help us when we share. Make sure you find someone who is trained and, if you don’t feel like you are being heard or they are helping, find someone else.

Several years after my aunt’s rebuke and her impatience with my healing process, I shared with a female friend at church. Sharing with the counselor had helped but the counselor wisely encouraged me to share with a friend. Me sharing, the counselor explained, can also create that sacred space where others find healing, too. That is the power of sharing. Choose someone safe, she said, but share. When we share safely, we create a safe place for ourselves and often for others, a place of healing. Amazingly, pain shared safely dissipates and loses its power over us.

Ask before you share with anyone other than a professional. Be aware that your trauma might trigger theirs. Always ask permission but ask and keep asking until you find someone to listen.

I did share and my friend was lovely and listened and the moment felt healing. The next day, though, her husband dropped by and stunned me when he said, “Mary told me what you told her.” I felt betrayed. How had Mary not known that I would not want others, especially men, to know? How dare she share my story? It was not hers to share.

“You just need to get over it,” he demanded. And suddently there I was again, back home, back where we keep our pain and illness in the dark, back where we keep secrets. I felt my pain rise up and choke me.

This time, however, I was different. This time it was the thought of going back into the darkness that had turned my stomach. “As it happens,” I told him, trying not to vomit, “healing apparently will only happen if I walk through the memory. They tell me I have to share to get well, so I’m gonna.” I was on the verge of apologizing to him for sharing with his wife because it had upset him so much when suddenly he sat down hard and started sobbing. Then he began his own sharing. He’d never talked about being a fighter pilot in VietNam and he desperately needed to tell someone. I don’t remember much of what he shared; what I do remember was being amazed that holding my own space for healing had created space for him. In that moment, he felt safe, too, and he stepped into that space for just a bit. We never talked again about his trauma or mine. Perhaps sharing helped him enough; perhaps he went on to seek more help because he, too, had seen the power of sharing.

Stepping out of the squirrel cage….

Mostly, the friends I reconnected with and I had individually found that, in an unexamined life, pain just gets passed down the line, generation to generation. We all were recipients of pain passed along, never knowing why or where it originated. The effects of trauma will keep rolling back around from generation to generation if no one stops long enough to find some healing and try to get out of that squirrel cage of crazy. Just ignoring the pain, or worse, denying its existence, guarantees the next generation will be expected to hold it, too, and they often have no idea the why or the where of that family trauma.

We may not have been able to protect our own children as well as we might have liked but it was not from lack of trying and we console ourselves by remembering that, because we have reflected, educated ourselves about trauma, shared with counselors, written and prayed, we have at least helped our children to get out of that damn cage. We may have done it clumsily, we may all be still rolling sometimes out of control on the floor after hurtling ourselves out of the cage, but we’re clear. We can take a breath. We can stop, stand back and reflect on that still-spinning wheel and maybe even pray for the family members still running on it. Because we are out, though, because we are talking, because we won’t hide any more, we have a fighting chance to NOT pass that trauma and dysfunction on down the line.

For a recent, well-done example of how trauma not shared can affect us and those around us, consider Tom Hanks’ movie, “A Man Called Otto,” or the book it’s based on, “A Man Called Ove,” by Fredrik Backman.

Leave a comment