When I shared the following events with my writer’s group and asked them to put a timeline on them, most guessed the 1950’s. Learning this occurred in 2002 disturbed them. Truly disturbing, though, is that, sadly, no one in this country right now would be surprised to enter a town square in nearly any southern state in the US and see again today what I saw then.

Sacred Bears

“Some old lady got my buddy in trouble!” was what I heard another pastor declare as I sat down at the weekly lunch of local United Methodist pastors in the county. (“Local Pastors” do not attend seminary but rather several years’ worth of courses in order to be allowed to preach from United Methodist pulpits.) I was running late, but I knew immediately what he was complaining about and I was annoyed to realize quickly he had only heard part of the story. “He was at the weekend school…”

“Course of Study,” I offered.

“Yeah. The Course of Study. Anyway, there was this festival on the square down there in Pulaski….”

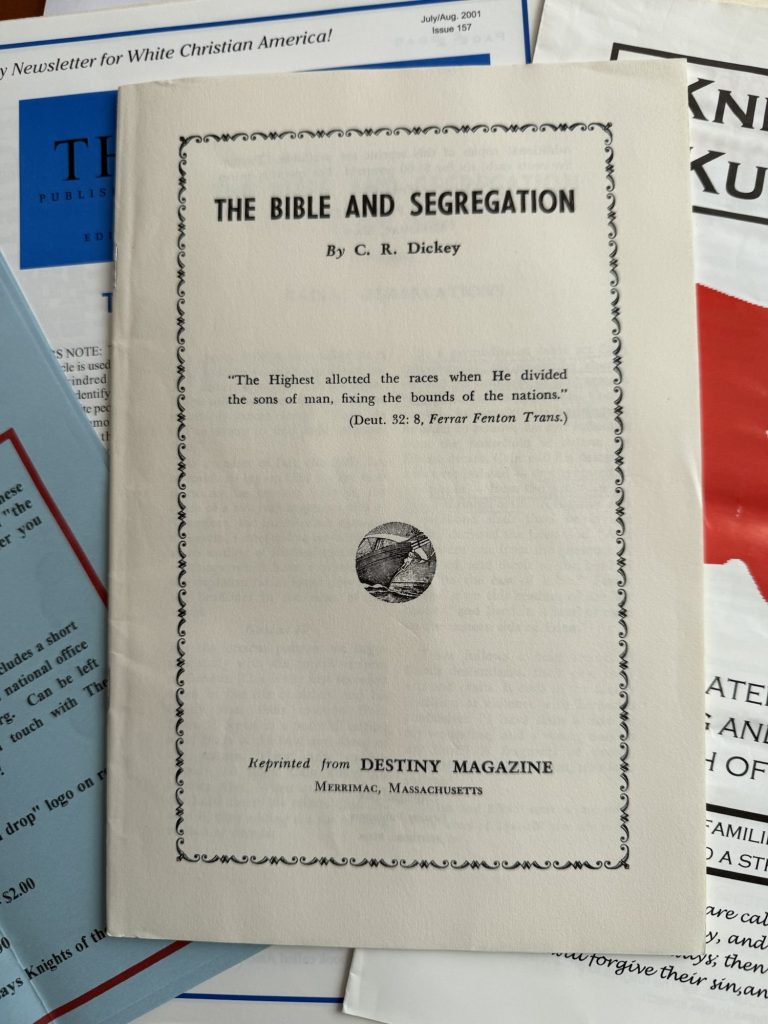

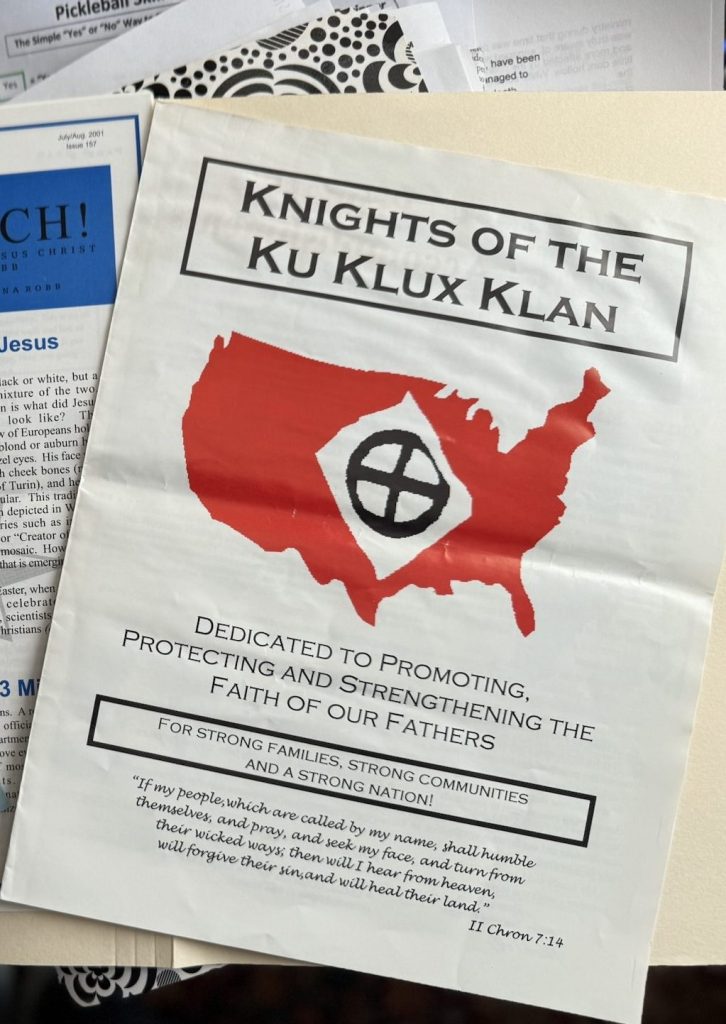

“They called it ‘White Christian Heritage Festival’ but they were handing out KKK literature,” I added. He frowned.

“Okay…. so, this old lady just took what my buddy said all wrong. Then…then, she told the guy in charge.”

“Grady?”

My colleague stared at me, determined to finish the story. “That old lady told Grady my buddy was part of the KKK!”

“Actually,” I said after I ordered my chicken salad with ranch on the side, “that ‘old lady’ told Grady that your buddy confessed to her that he could see where their teachings made sense. He said they made sense.’ So, since he is allowed to preach at a United Methodist church and to teach children and youth….”

“She probably just misunderstood.”

Surely, I thought, this guy will catch on soon. I sighed. “So, I shoulda just let that slide?”

The others at our table were clearly amused that my colleague didn’t get why I knew the story so well. In his defense, he attended a different Course of Study, lasting four weeks, in Atlanta for full time pastors in the United Methodist Church. His buddy and I were part time, which meant only 60 hours a week of work. Our Course of Study classes met over eight weekends a year with reading and papers in between those weekends, sometimes in Jackson and other times at Martin Methodist College in Pulaski. Pulaski, if you aren’t aware, is known for being home to some members of the Mars candy family (think Milky Way) and is also generally credited with being the birthplace of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the KKK.

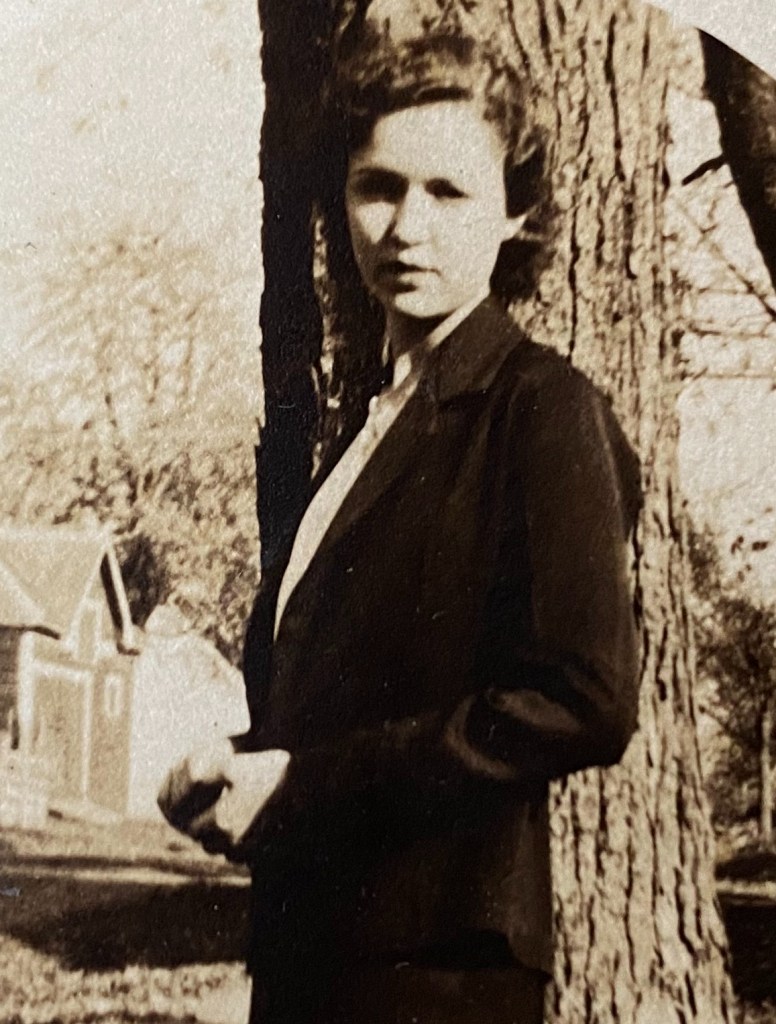

I especially hated the overnight stays at these weekend schools. That particular weekend, I do not remember another woman in attendance. Not only was I away from my sons, but I was alone. In a motel room. In a strange town. A single woman. Newly in recovery from trauma. In other words, someone who knew bad people did lurk in the shadows. Assuming all the men around were trustworthy was a luxury. So, I slept not at all. I took to wedging whatever chairs were in the room in front of the door in an effort to at least rest.

On one particular Saturday, several of us left class to make a lap around the nearby downtown square on our lunch break only to encounter what was that day touted as a “Celebration of Southern Culture.” Displayed on the assorted tables were handtooled leather goods, canned peaches, okra and pickles. A brochure I found had previously invited area residents to join in the “family fun,” including a cakewalk.

Pretty quickly, though, I was stopped, jolted a stuffed teddy bear sitting among the books and maps under the magnolia trees. I believe God created Teddy Bears to provide a tactile reminder of love and affection, of comfort. This bear, though, had, through no fault of his own, become aligned with pure evil: he wore a white cotton robe and a white pointed cap that covered his face. This child’s toy was disguised, as if he, too, needed to hide his collusion with evil, like the men who had donned those robes and hoods in the night for so long. I thought they were a thing of our past and yet there they were, not hiding their affiliation at all and they had brochures, newsletters, books and even maps, the texts and visual aids to present these “Southern” beliefs. The first murmurs from the other pastors with me were indignant: how did these folks get to determine the definition of what was “southern”?

Eager to share with us about how God meant to order society, one of the men began to carefully explain the rationale for hatred, including their understanding that God, of course, looked just like them. In that moment, the inference was that God most resembled a skinny, pasty middle-aged man in black slacks, a white shirt and a decades-old tie. A couple of pastors seemed interested in engaging. I was far from confident in my ability to face evil head on though; I, instead, focused on the contents of the tables.

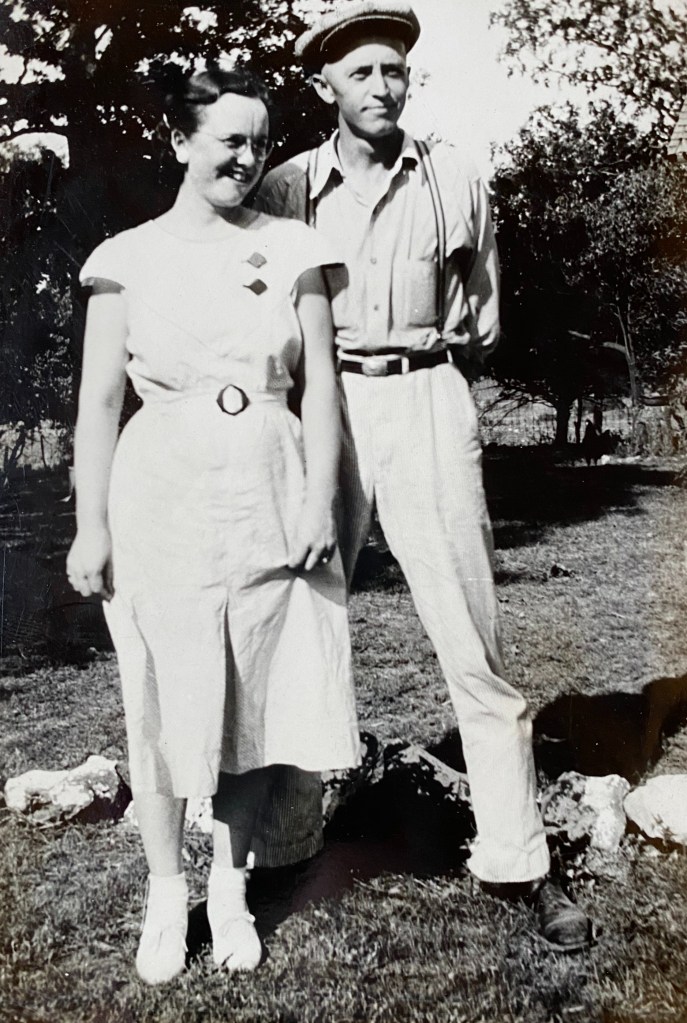

Besides books and t-shirts, decals, key rings, watches, pins and flags, there were maps. I would not give them my money for books but I did consider buying one of the maps, a large laminated wall map designed to settle once and for all the mystery of the disappearance of the two “Lost Tribes” of Israel. Finally, I chuckled. They’d migrated, it seemed, from the Middle East and crossed over the Caucasus Mountains, stopping, of course, in Scotland before heading into North America. My ancestors were among those Scots who came through the Cumberland Gap and moved on into Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri. I hadn’t known, however, that we were either lost or a tribe of Israelites. This journey was credited with solving the mystery: the Lost Tribes were now known as “Caucasians,” according to the map, by virtue of having traversed the Caucasus Mountains. I kick myself now for not purchasing that map, but, at the time, I could not stomach giving these people my money.

I did try to offer them money for the Teddy Bear, for the sake of the children these men likely influenced, for the sake of the legacy of Teddy Bears the world over, and for the comfort and benevolence children had so long depended on them to provide, I wanted to scream, “How dare you?!”

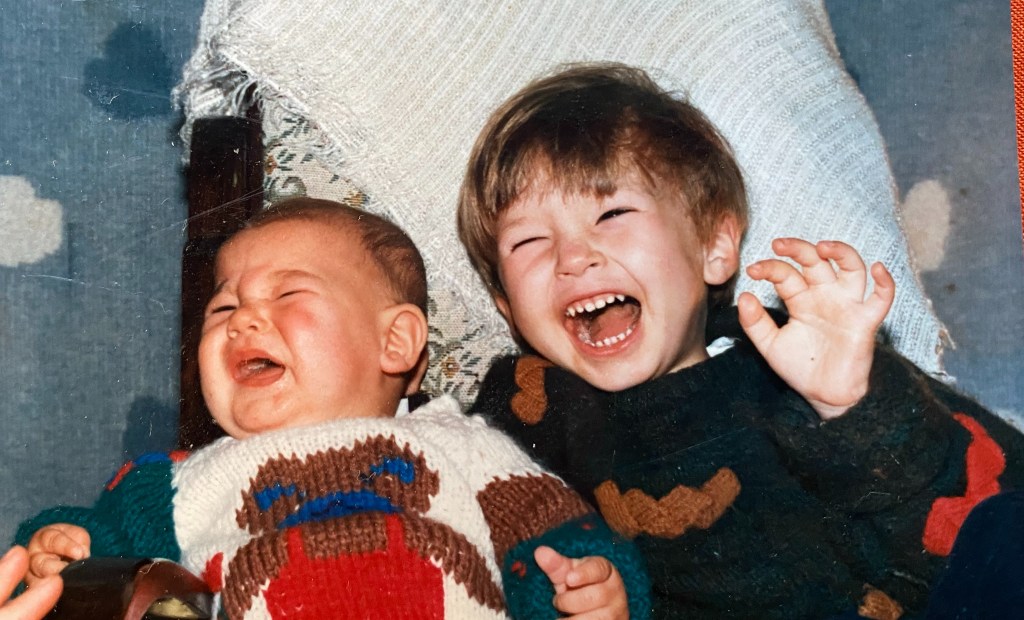

Gotta hand it to the KKK, though. Aligning an innocent source of comfort and safety with the evil of the KKK, twisting what a child loves and trusts and using it to promote hatred and exclusion is socially and theologically powerful. Teddy Bears are bordering on sacred, as far as I’m concerned, objects that carry children through those times when the adults are absent or preoccupied or already asleep.

The Teddy Bear in the hood and robe makes more sense when you recognize how much of the most destructive theology through the ages has been born out of childhood pain. We may never know who was the child who’d been hurt enough that he grew up and somehow chose to cover himself and his head and face with a white hood so his grandmother or his neighbors or his children did not see him when he was cruel and ugly. I wanted so badly to rescue that child, or at least rescue the Teddy Bear, to allow God to do what God does best: redeem both that Teddy Bear and whomever it was who dressed him up.

I wanted so badly to rescue that child, or at least rescue the Teddy Bear, to allow God to do what God does best: redeem both that Teddy Bear and whomever it was who dressed him up.

“He is not for sale” was the response, though, and so I left behind that embodiment of evil and prayed for the trust and spirits of all the children these pasty white men were teaching or had taught so far.

I did pick up some brochures and printed newsletters and walked away before they realized I did not, in fact, agree with their understanding that our country was designed as a White Christian nation or that we ought to somehow respect men who hid behind masks to terrorize others. Later, I would discover the literature went so far as to advocate for internment facilities for those who had contracted AIDS, for example, or that we all were invited to a worship service that night, complete with “great white Christian fellowship” and a “brilliant cross-burning!”

I was no longer hungry, so I walked back with one of the younger pastors. After a few moments’ walk in silence, I said simply, “I was not expecting that.” I was feeling shaken that this evil was so openly displayed and discussed; I’d been blissfully ignorant, I realized. I had honestly thought these clowns in hoods were anachronisms, relics of a bygone era, that they were no longer active, like the sundown signs I would later learn sat as sentinels along the highways at the edges of the town where I preached. Those signs–simple painted sunsets on road signs–were nonverbal warnings: if you were a person of color, you’d best not be found in this town after sunset. The signs had been taken down, but the sentiments, fears and prejudices were not so deeply buried. I would later be disturbed to find out, for example, that two members of my congregation had been “card-carrying” KKK members while I was pastor there. As a white woman, I had been ignorant and thus, negligent.

As we walked back to classes that weekend, though, my companion, a pastor who was about 15 years my junior, pointed out that “southern culture” was his culture. Then he added, “They did make some valid points. Did you realize they’re Christian?”

The hair on the back of my neck stood up.

“If you listen to what they are saying,” he went on, “you will discover that they make a lot of sense.”

He was a pastor.

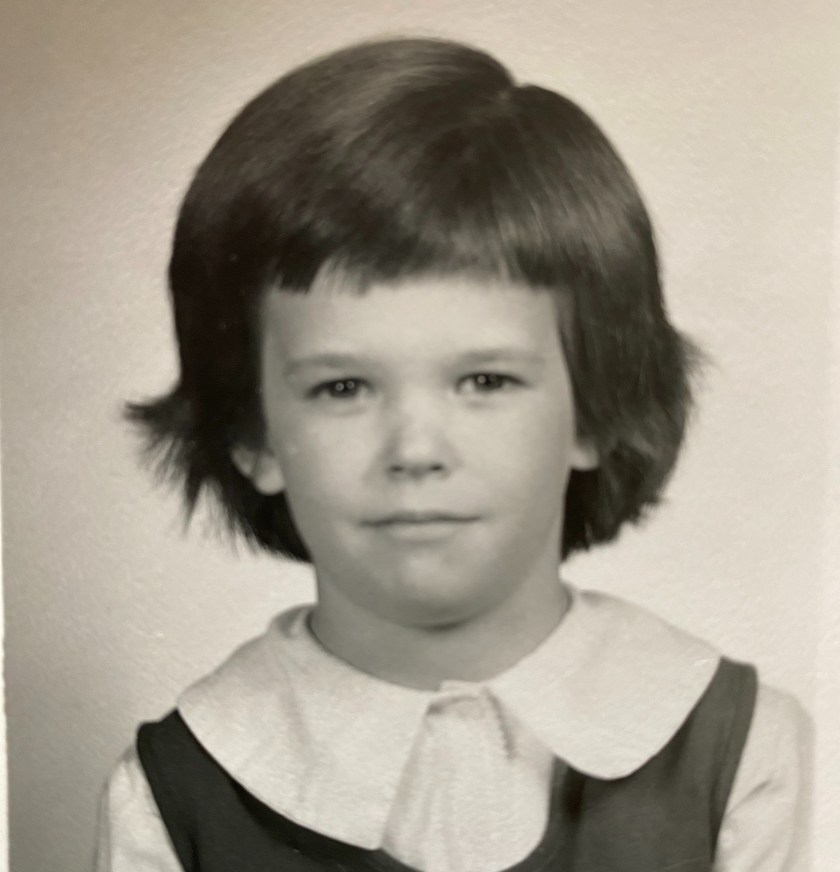

He taught a children’s Sunday School class, too, and he seemed interested, not disturbed, but interested in the Teddy Bear in the robe and hood.

“How,” I asked as calmly as I could while placing one foot in front of another, “would you go about teaching this to children?” I wanted him to clarify, to make me realize I’ve misunderstood, to tell me he wasn’t teaching ‘southern culture’ to the children, but he didn’t say any more. As we approached the classroom for our last afternoon that weekend, I wondered what the other pastors might say. Turns out, very little. I remember watching the others in the rest of the day’s lecture and discussion, wondering why no one mentioned what we’d seen. Had they debated at lunch? Had they discovered others open to these ideas? No one seemed angry, at least not that they’d admit. I felt like I was playing a game my sons liked where you had to pretend that the floor was lava, so don’t dare put your feet down; it was dangerous. I hoped that the overt racism we’d witnessed had shocked them too. I feared, though, they knew from experience not to admit out loud they “got” where these guys were coming from, that, like my walking companion, they knew to simply shut down the conversation if they thought they’d shown their own hood to the wrong person.

Once we’d finished for the day and each of the pastors was headed home to prepare to preach the next morning, I found Grady, the professor in charge. I explained I did not want to cause an issue for a colleague but I was disturbed about what this pastor might be teaching, especially in Sunday school for children. I wasn’t sure what to do and had not felt safe addressing him directly. Grady listened, got the particulars, then told me it was his place to address it.

I heard nothing else for a month until I received an email from Grady; he’d spoken to the younger pastor’s District Superintendent, who evidently had found “no reason to believe such reports” and had never even spoken to the guy. This information hit my inbox just before leaving for the next weekend class. Once there, I was dismayed to find that the young pastor was there before me, annoyed, and looking for me. He was pretty sure I was the one who had ratted him out. I was the only “old lady” there.

He greeted me with “I got called on the carpet by my DS,” which was a stark departure from what my professor had been told. “When can we talk about this alone?” he wanted to know.

“Excuse me,” I said, walking away; that was as much as he got for the rest of the weekend from me.

I still count that entire episode a disappointing failure, though I didn’t know how to do anything differently at the time. Not tossing my books and overnight bag in my car and leaving right away seemed the best I could manage for the time being. Clearly, I needed to learn how to counter this twisting of theology openly, to be prepared to teach the children and youth in the churches I served that Jesus really meant it when He said He loved every body. So I stayed. For the rest of that weekend, I kept my distance. I kept my guard up. I didn’t sleep.

I wasn’t surprised then a few weeks later at lunch, though, when this “old lady” was being castigated and labelled a busybody sticking her nose in other people’s business.

Just to be clear, I asked my angry colleague, “That old lady ought to have simply looked the other way?”

“Exactly!” he said. “It was none of her…your business.”

Leave a comment