A favorite talisman from Pakistan. I loved how all the different sizes nested one inside the other. I’ve carried this painted wooden toy with me for nearly sixty years now. Cracked and repaired, broken but still beautiful, a cradle of memories.

When I was seven, my brother, who was eight, my sister, who was six, and I got dumped in our grandparents’ laps, a harsh ending to what had begun two years earlier as a grand adventure, meant to last a lifetime.

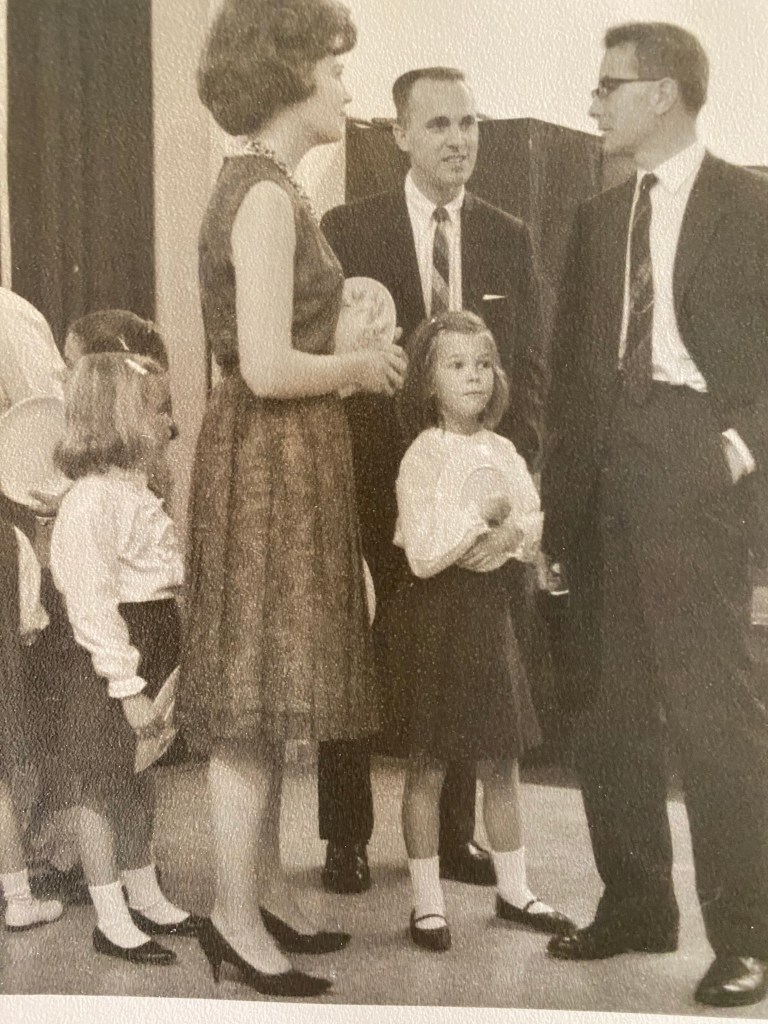

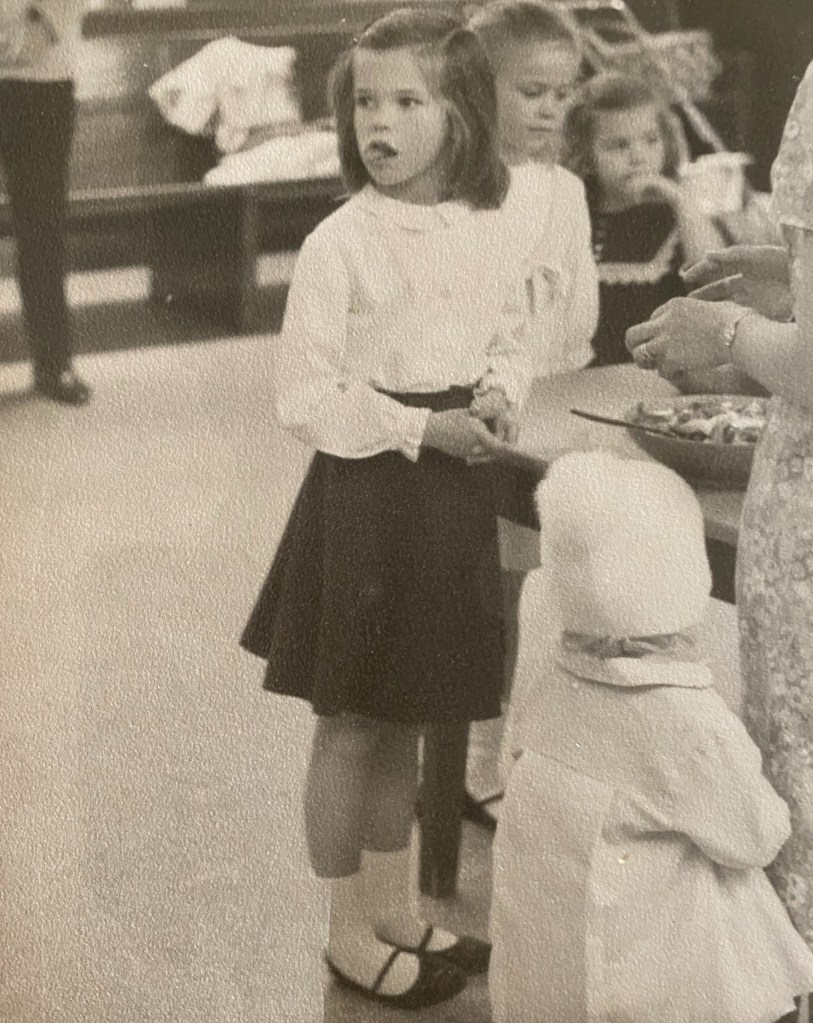

Once it was announced that Dad had secured a coveted engineering job overseas, we had all been celebrities at one festive send off after another from Springfield, to the unknown and mysterious West Pakistan, (now Pakistan). The biggest Bon Voyage event, where each of us had been presented with brand new suitcases to go with our brand new outfits for the journey to the other side of the earth, reflected how impressed friends, coworkers and neighbors had been when Dad had secured the contract.

That the way to Pakistan involved so many shots for so many illnesses was annoying, but, for me, the memories of those jabs are overshadowed by those of international flights on Pan Am where the pilots brought all the children on the flight into the cockpit and each of us received a souvenir Pan Am flight bag and our own set of pilot’s wings. I remember buying a doll in Tokyo, where I was convinced that I could speak Japanese because I could speak to the sales clerk. I remember arriving in Karachi to be served warm milk and runny eggs and that we slept twenty-four hours before driving to our new home in a walled compound in Northern Pakistan. I remember much about our time in Pakistan, but I do not remember the trip home.

Thoughout the two years we were there, Dad was likely excelling in his work, but, before the contract was completed and we could be posted at yet another overseas project on another continent, Dad was forced to break his contract and return to the states on short notice, with little or no money, no job and much anger.

So, just a few days after boarding a plane for home, the three of us children found ourselves seated in a row on the edge of the bed in a motel halfway between our grandparents’ home in the little town of Waynesville, Missouri, and wherever Dad had found a job. The motel bed was low to the ground; our toes just touched the linoleum and we were each individually toeing the floor and pushing the old bed up and down, causing the box springs to creak softly. Next door, we could hear our parents and grandparents arguing loudly. We did not know then the three of us would not be going to the tiny apartment Dad had managed to find.

I clutched my Chatty Cathy doll. Bless her heart, she’d stayed with me throughout our time overseas in spite of looking like she had mange because my little sister had taken a pair of scissors to her black hair. My sister clutched a stuffed monkey who had a permanent grip on a plastic banana. She had already given up the doll she’d been given, one who giggled when her arms were squeezed, and who likely ended up in another child’s arms, looking like she was just out of the box with that curly, blond hairdo intact. Don’t think it didn’t cross my mind, though, to experiment on her with scissors. Maybe my sister was just more angry at that time than I was.

“Say goodbye to your children!” my father had hissed moments before all three of us climbed in the back of our grandparents’ sedan. Mom’s eyes were already glazed over though; she wasn’t responding. She had said nothing while my father had been yelling for weeks, it seemed, most recently in the next motel room, in front of her parents, who also were silent. We couldn’t hear any of those angry words at all, only loud voices, then we each flinched as the door to our motel room had swung open and we saw our parents standing there. “Say goodbye!”

Grandma Ree and Grandpa George seemed just as dumbfounded as we were, I think, and were really in no financial position to take on more, but to their credit, they put the three of us into the back of their tiny dark blue sedan anyway. Driving away from that motel, each of us rode silently, wide-eyed, tacitly agreeing it was better not to ask.

His Adventure; Her Nightmare

On our way home from Pakistan, we’d each been wearing a new pair of leather shoes made from a cobbler in Pakistan. Even finding shoes while we were there became an adventure for my father who savored every side trip to a bazaar and whose shopping addiction devoured cameras and jewelry and handmade rugs and carved tables with ivory inlay for playing chess. Being there while the country was at war with India was a nightmare for our mother, though; after my parents ventured to the bazaars, she had nightmares about the children who had been purposely maimed in order to make their begging more lucrative. By the time we left Pakistan, Mom had begun obsessing about keeping the windows covered with foil for nighttime blackouts, long after it was necessary.

The civil engineering position Dad had secured with this company overseas was his dream and meant to last his whole career; he had not planned to have to return to southwest Missouri with his family at all, certainly not as a quitter. This contract was his chance to escape small towns and small minds, and that dream was not meant to die a quick death because his young wife discovered the balm of alcohol and realized that some men could be sweet. Mom, bless her heart, had been thrust into a world she had never contemplated and one she was vastly unprepared to engage, understand or master. Dad, on the other hand, had served overseas in the Air Force and, when he returned, he invested in National Geographic in order to know more about the world he had only tasted in his two years in Puerto Rico. This job had been his chance to immerse himself in adventure and travel.

A small-town girl who had never left Missouri before, Mom continued dutifully each day to don a crisply ironed dress and heels while struggling to learn to oversee servants, like the first one, a “Bearer.” The Pakistani manservant who did not speak any English was in the house all day, and ironed and cooked unrecognizable meals for us. He didn’t last long. A gardener, a “Mali,” was required, if only to keep up appearances in the European-style neighborhoods built by the company that had brought so many engineers and families from all over the world. We knew, though, that walking outside one morning to find the gardener, proudly holding up the cobra he’d caught in the yard where her children played was too much for Mom. She began to unravel. Our father held out, though, and doubled down on social activities, including starting a Boy Scout troop, in hopes Mom would adjust. Instead, she discovered the alcohol that had never been allowed in her home growing up. She found the mathematics of rum, to be precise. One drink made her feel good, two made the barbed wire on the compound walls fade, and four drinks made all the lizards and maimed children and strange men in the house just slip away for hours and hours.

Pictures courtesy Jodi McCullah All Rights Reserved

We never saw Mom drink, though. We were in bed every night by seven p.m. We never saw her drink and we never saw our father much at all. For the two years we lived in Pakistan, our father kept twelve-hour work days and so our paths did not cross for two years, except on the occasional family shopping outing. During those two years was the only time we had allowances and every few weeks, the family would venture to the compound’s shopping area where we could find a Pakistani furniture store, a European-style restaurant complete with a dessert cart filled with petit-fours, and a toy store, where we were happy to spend our allowances, most often on comic books since there were no Saturday morning cartoons. We had no television at all in our home there, in fact, so by the time we left after two years, we had amassed more than three hundred Archie, Superman and Richie Rich comic books and often participated in a robust trading circle with other neighborhood children. Once, though, we all three saved our allowance to buy a pale blue scooter that we could see high up on a corner shelf in the toy store. We visited that store several times without buying any new toys or comics, simply to be sure no other children had purchased that little scooter high up in the corner. We were struggling not to run or pull on our father’s hand to get to the store when the day for purchase finally arrived. Together, the three of us proudly plunked down our rupees onto the counter and watched, holding our breath, as the store owner pulled the scooter down and dusted it off. When he rolled it around the corner of the counter, however, to present that blue beauty to us, my older brother and I realized that the scooter, heretofore only viewed from afar, was too small for either of us. Only our little sister would be able to enjoy it. There was no going back, however. The store owner was beaming at having sold the toy that had taken up his store’s top shelf for months and our father would have been too embarrassed to halt the purchase. Typical of our relationship, though, my brother and I did not commiserate; we were silent as our feet dragged on the dusty road going home. Our sister stayed on the sidewalks with the scooter but I do not remember her using it very often after that, which only added to our disappointment.

Other than the occasional shopping trip, church and the bowling alley, we did not see our father. Even at those venues, we did not interact with him. Our understanding was that, like the other engineers who worked long hours building that dam, our father was excused from many family activities. When we did participate as a family, like at the bowling alley, the children went off unsupervised mostly, so we still didn’t see our parents unless we were causing a problem. Dad was apparently a minor celebrity at the bowling alley, though, often bowling perfect or near perfect games. Our time there consisted of ordering tuna fish sandwiches and zombies to drink at the adjacent grill and watching, fascinated, as the Pakistani workers reset the pins after each throw of the ball. No automated pin replacement there.

Though I was very young, I remember a lot about when my Father was helping in the beginning years to build Mangla Dam in West Pakistan, now Pakistan (as opposed to East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.) Most of our old photos from that time, however, are lost. I do remember that strange juxtaposition of Western and Pakistani. We attended a British school where I learned some Urdu and to add an “e” in the middle of judgment, (i.e., British spelling) a bowling alley and we enjoyed a wonderful series of public pools. We also explored some historic sites and went to school with children from all over the world, including Pakistan. (See Wikipedia, Mangla Dam and Mangla Dam Memories on Facebook.)

Otherwise, the three of us were on our own outside of school hours. The compound was large with an American side and a European side and a bus that drove around both sides all day. On any particularly boring day, the three of us would simply climb onto the old, repainted school bus and ride down all the streets of both sides of the compound, cooled by the hot wind coming through the open windows and fascinated by what our neighbors might be up to that day. I am still amazed that we were simply allowed to wander at five, six and seven years old. In Pakistan.

The entire adventure seemed a contradiction in terms, characterized for me by the fact that we lived in a compound surrounded by a stone wall with barbed wire and cut glass on the top but where the gates were always open and unguarded.

There was an open gate at the back of our own yard, in fact, and from it, we could see a small village where, we were told, women slapped cow dung onto the walls of the homes to dry to be later used as fuel for the fire. Every day, we could hear the calls to worship; they were haunting and beautiful, a call to an Islamic understanding of God that serenaded us as we walked to our Christian church potluck supper. For some of the year, the dust on the side of the road was a fine and deep silt and we would slide our feet through it as if it were snow; other times, during monsoon season, there seemed to be nothing that was dry.

Unsupervised. In Pakistan. At age 7.

That we were largely unsupervised outside of school hours made sense to someone I guess. Until the injuries began. First, my five-year-old sister got stitches trying to climb up a ladder to dive off of the high dive at the crowded community pool. Then, I nearly drowned just a few feet from my mother in the same pool; another mother noticed me struggling to keep my head above water and grabbed me. Mom was busy chatting. There was a broken arm, then stitches for me. Twice. This time, however, neglect was not the problem. I had become the target of choice for my older brother who gleefully ran his bicycle into mine, causing the pedal to tear into the fleshy part of my lower right leg, leaving white tissue oozing down my shin. He later threw a cutting board at me, just missing my eye socket but also requiring stitches. We may never know if another parent intervened or if our father walking into the living room to see our mother kissing the neighbor, but there came a day when Dad sat all three of us down on the edge of a bed in our shared bedroom to tell us our mother was ill and would be “going away” for six months or more. It had been decided we three would wait for her there, in Pakistan.

That’s when the wailing began. Paid mourners could not have been louder or more dramatic. At the time, we were terrified, but we were also resolute, huddled together eyeing that dark and dangerous chasm that seemed to open up before us. We did not know this man. No way were we letting Mom go quietly. We did not stop crying until Dad returned to the room hours later to tell us we were all going home.

Our relief was short-lived, though; once my father dragged Mom away from that motel, we did not see or hear from our parents for months and months. The timeline is vague for me but I remember attending three schools in second grade. So, once we were settled in my grandparents’ two-bedroom duplex in Waynesville, I took to running away, searching for her. From school, from my grandparents’ home, even from church services, I escaped, watching for unsupervised moments and unlocked doors, taking advantage of crowds and distracted adults, always looking for my mother.

Pictures courtesy of Jodi McCullah All Rights Reserved.

More than once, because Grandma Ree was exasperated, I was simply allowed to stay home from school on my grandfather’s day off and we watched cartoons and ate Oreos while he ironed the work shirts he wore driving trucks. Grandpa George seemed to me to be the only adult who was not angry with me; I remain convinced that was because he understood my quest.

Once, after I’d run away from school, the school principal found me. He and a teacher picked me up in a car after they’d driven all over that little town looking for this wayward seven-year-old.

“There, there,” he said, offering me a piece of gum in a green wrapper folded around shiny foil, very much a treat then. Defeated for the moment, I cooperated and got into the old car, only because I’d been wandering for hours and it was getting dark. Offering me a stick of gum, though? Did the adults around me really think that would fix this? I remember looking at him as if he were clueless. It would be years later, though, before I could be proud of that seven-year-old slapping that piece of gum from the principal’s hand in the back of that car, and even longer before I could appreciate the courage it had taken for the three of us to stand up to our father.

We all paid a price, though; we would never have back the mother we had known. When we saw her again, she was subdued, defeated. She had endured shame, therapy, even, we were told later, shock treatments, all because her dream was not his dream. She was not unlike many women of her day, praised for obedience like a child. For the rest of his life, though, my father was on notice. I’m not certain to this day that we accomplished much, but our little rebellion was uncharacteristic of us and I am proud to be able to look back and say that those three little souls refused to go quietly into the darkness.

.

As the layers of your life unfold, Jodi, I admire the person you have become even more. God surely does work in mysterious ways. Bless your little seven year old heart.

LikeLike

Thank you, Nancy. I hope you know you have been a great source of encouragement.

LikeLike