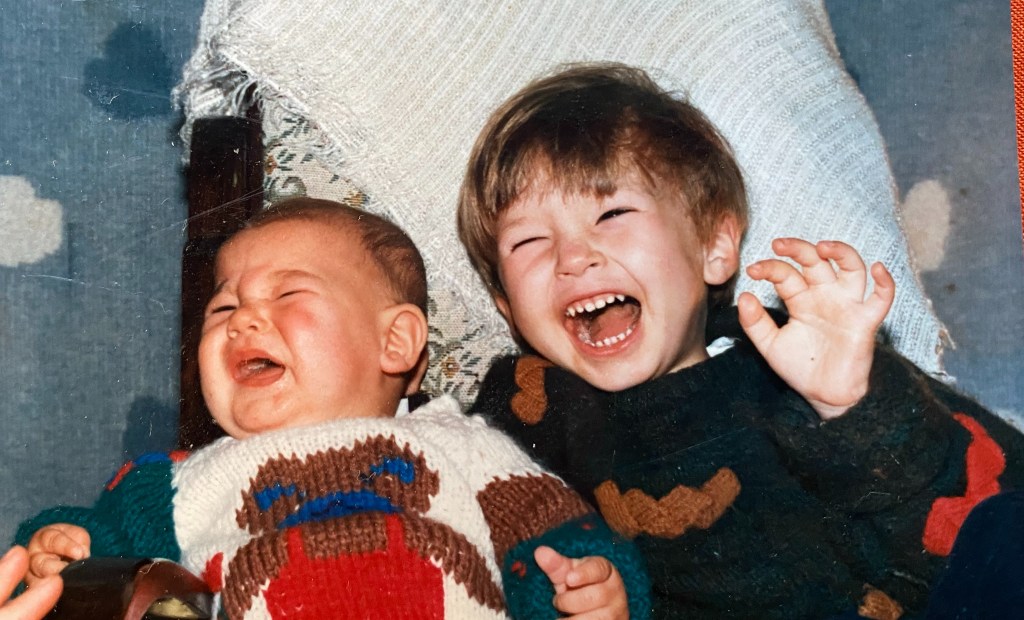

When our two adventurous boys were toddlers, their father, Mick, the bearded, brown-eyed singer I’d fallen in love with a decade before, demanded I stop being constantly worried about the survival of our off-spring.

“They’ve made it just fine so far,” he said one warm evening outside Kroger, punctuating his point by, rather roughly, I thought, depositing our two-year-old, Spencer, into the basket of a creaky shopping cart.

In my defense, I countered silently, we had thus far prevented any plaster casts or spidery-black sutures on those precious cheeks because of the diligence and quick reflexes of their mother and the fact that the two-year-old, in particular, bounced well.

The first time I’d left my husband alone with Arlo, our first-born, to play at the park, I had not realized I needed to explain to him that the rubber, wraparound baby swings were for one-year-olds like our son or that he was nowhere near big enough to sit on a sagging rubber seat meant for an older child and hold onto a chain. Our beautiful brown-eyed boy got his first bloody nose that day. My husband read my mind.

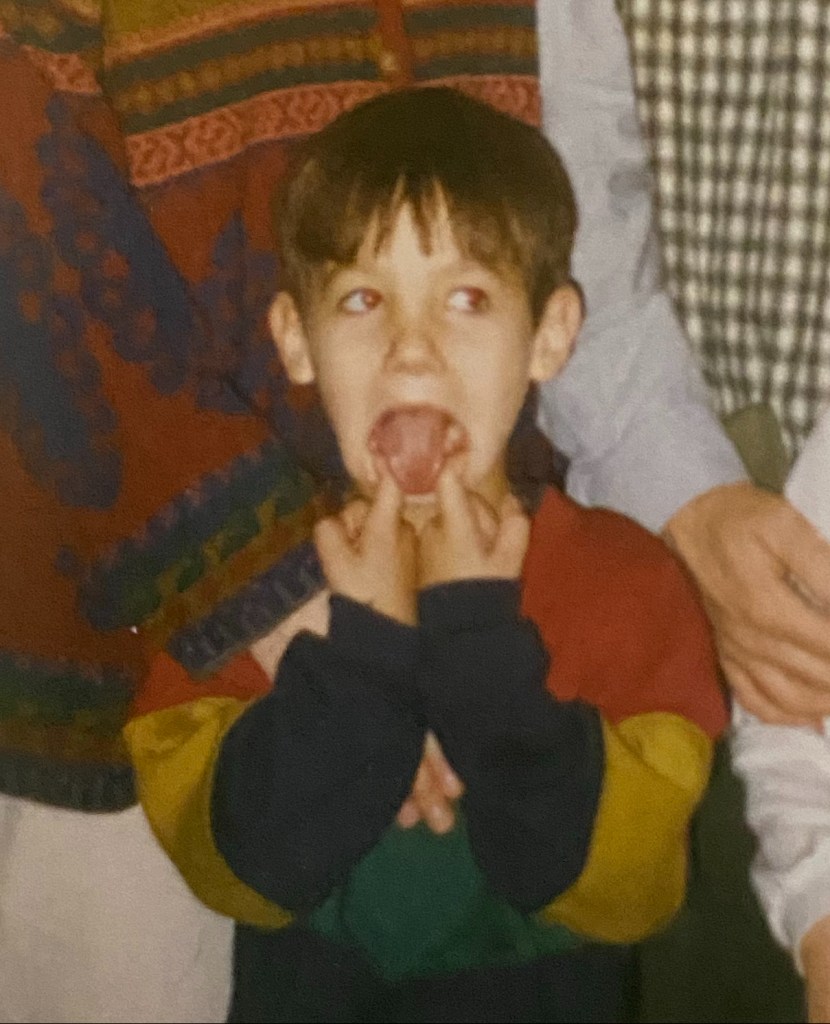

“It’s not like he broke his nose when he fell from that swing,” Mick countered while helping the now four-year-old into the cart. Arlo wrapped his arms around his bent knees and lowered those eyes onto the patches on his jeans, happy he wasn’t going to be expected to walk but pouting because his father had said no toy aisle.

I frowned at the squeaking of the wheels as we pushed the cart towards the sliding glass doors. I pointed to the two-year-old, and commanded, “Sit.” He sat.

“We know better now than to leave them alone with anyone else,” he said, both of us remembering our last visit to his parents in this now well-worn argument. His mother had suggested a fifteen minute stroll down to the dry creek for some time alone only to discover on our return to the house that Spencer had burnt the palm of his chubby little hands because no adult was paying attention.

“I wasn’t there though,” my husband continued his line of argument. “Even when I’m here with them, you worry.” He pointed out to the busy parking lot. “I see,” he said, “cars and parents and grocery carts out there. You,” he said, sweeping his arm across the parking lot like Vanna White, “you see death everywhere!”

He wasn’t exaggerating.

I did see death everywhere, especially in parking lots. We had spent the past four years in a small Japanese town where there were few cars and the biggest danger for a child was being smothered by too much attention. Back home, however, new dangers lurked everywhere.

“You just go shop. Alone,” Mick suggested. “I’ve got them and we will get home a whole lot sooner if you just pick out the apples and chicken alone. Okay?”

He abruptly parked the cart by the magazine rack. “We’ll be right here. We’ll be fine. We can be home soon if you don’t come looking every time you hear a child crying.” I slunk away under the weight of his disdain, clutching a plastic hand cart and thankfully-short grocery list scribbled on the back of an envelope. He was right. I did not need to assume every crying child was yet another example of Mick being distracted at just the wrong moment.

I first heard the clatter of metal on the tile floor as I left the cereal aisle. Someone has knocked one of those end displays, I told myself, honing in on the bone-in chicken breasts at the meat counter. I chose a shrink-wrapped package whose price sticker showed it to be family-sized, then turned towards the milk display. I wrinkled my nose as a sour smell hit me: milk had been spilled at my end of the store. I skirted the spill, and reminded myself of my goal. I had focussed and was still going to focus, I told myself, pushing the cart away from the sound of a child crying at the other end of the store. “Not all crying children are mine, not all crying children are mine,” I sang to myself to the tune of the “Wheels on the bus.” Whoever they are, they are with their mother and my boys are fine, I reassured myself.

One gallon of two percent secured, I headed to the express lane. I set the items on the grocery belt and tried not to look towards the gathering crowd near the far end of the store and the self-checkout. I smiled to myself, proud of progress, then stopped the cart abruptly, and leaned back to look around the endcap filled with M & M’s and sugar-free gum to see my husband holding our two-year old. The four-year-old had a firm grip on his father’s thigh and a store clerk was dabbing Spencer’s face with a cloth. Leaving apples, chicken, milk where I had neatly organized them, I forced myself not to run. Mick looked up and apologetically. The four-year-old did run and I scooped him up without breaking stride. I looked at the overturned cart and then at my husband in horror.

The store clerk backed up to let me assess the two-year old; he would have a bloody and swollen lip but no teeth damaged, no need for stitches and neither had broken any bones, it appeared. A miracle.

“I was looking at the magazines,” Mick explained. “Arlo must have reached over for the children’s books and made the cart fall over. They’re okay, see?” Mick turned Spencer’s chubby, snotty cheeks towards me.

I set Arlo down, put the crying child on my right hip and sighed as he wiped his nose on my shirt. Arlo grabbed onto my left hand, then looked back at his father as we started for the door. Mick took the bags of groceries from the manager who apparently had followed me from the 10 Items or Less checkout. “Did you pay…?” Mick’s voice trailed off behind me and I heard the manager encourage him to take the bags and go, please.

I kept walking.

“Never.” I said, without breaking stride, not really caring if anyone heard me.

“Never tell me again how to be a mother.”