As stories go, this one is incomplete, like a puzzle missing some corner pieces, or a picture torn, by accident, of course. It’s my hope that through this process of unpacking my backpack of memories, I’ll locate those missing puzzle pieces or that torn corner of the picture and all – or at least more – will make sense.

Some years ago, I went looking for, or at least information about, my teacher from third grade. I’m sad to say, so far, I haven’t found her, though I am pleased to report I’ve found some folks I’d lost track of some decades ago. As the child of a father who moved us to new cities – and even new countries – at least every three years, I certainly have felt disconnected. For the longest time, because I also was estranged from my family, there existed no one in my life who could vouch for me ever existing prior to college. No one would say, for example, “You were always the tall one in the class.” No one was ready and eager to remind me that I was always late for the traffic patrol crossing guard duty – dear God, they let us do that in sixth grade then! No one would raise their hand to verify – or deny – if I were accused of being teacher’s pet (I sure wanted to be.) or if I had read every historical biography in our primary school library. (I had!)

Thorpe J. Gordon Elementary

I attended Thorpe J. Gordon Elementary School in Jefferson City, Missouri, from the last part of second grade until sixth. We arrived after living overseas for a couple of years (There’s another couple of items from the backpack and a few more stories for another cold day). Today, though, I am seriously regretting tossing all those class pictures a few years ago. You know, the ones where we all stood on those metal risers and tried to hold still long enough for the photographer who counted it a win if he could get us all looking at the camera when the bulb flashed. (If you have pictures from Thorpe J. Gordon Elementary in the mid-sixties, by the way, I’d love to see them.)

To the best of my recollection, my teacher when the year began was a Mrs. Peterson (sp?). She was young, pretty, energetic and fun, and we all loved her.

At least that’s how I remember it, but then, for the longest time, I remembered this as happening in second grade. Since I didn’t start Thorpe J. Gordon until after Christmas in the second grade, seems like some memories got fragmented and some pieces indeed might be missing. We do all have somewhat mashed up, muddled memories, don’t we? I don’t know about you, but whether they are from last week or our childhood, my memories toy with me.

In my mashed up memories, Mrs. Peterson was lively and pretty and cheerful, which was amazing because she was married to a Soldier. Mr. Peterson was, at the time, serving in Viet Nam. He was at war. We didn’t know why he had to be at war but we knew she didn’t get to see him or talk to him much and he wasn’t at home when her day was over. We knew too that he was a pretty nice guy because, every time he sent a cassette-taped message to his wife, he included a message for our class. In return, when Mrs. Peterson was preparing her own cassette message, she allowed us to add some greetings and questions. Sometimes, much to our delight, in the subsequent message, he answered those 8- and 9-year-old’s questions. We felt special and connected and heard, both from him and from her, something most children could not say in that generation, to be sure, and something that, sadly, would not last.

Christmas Corsages

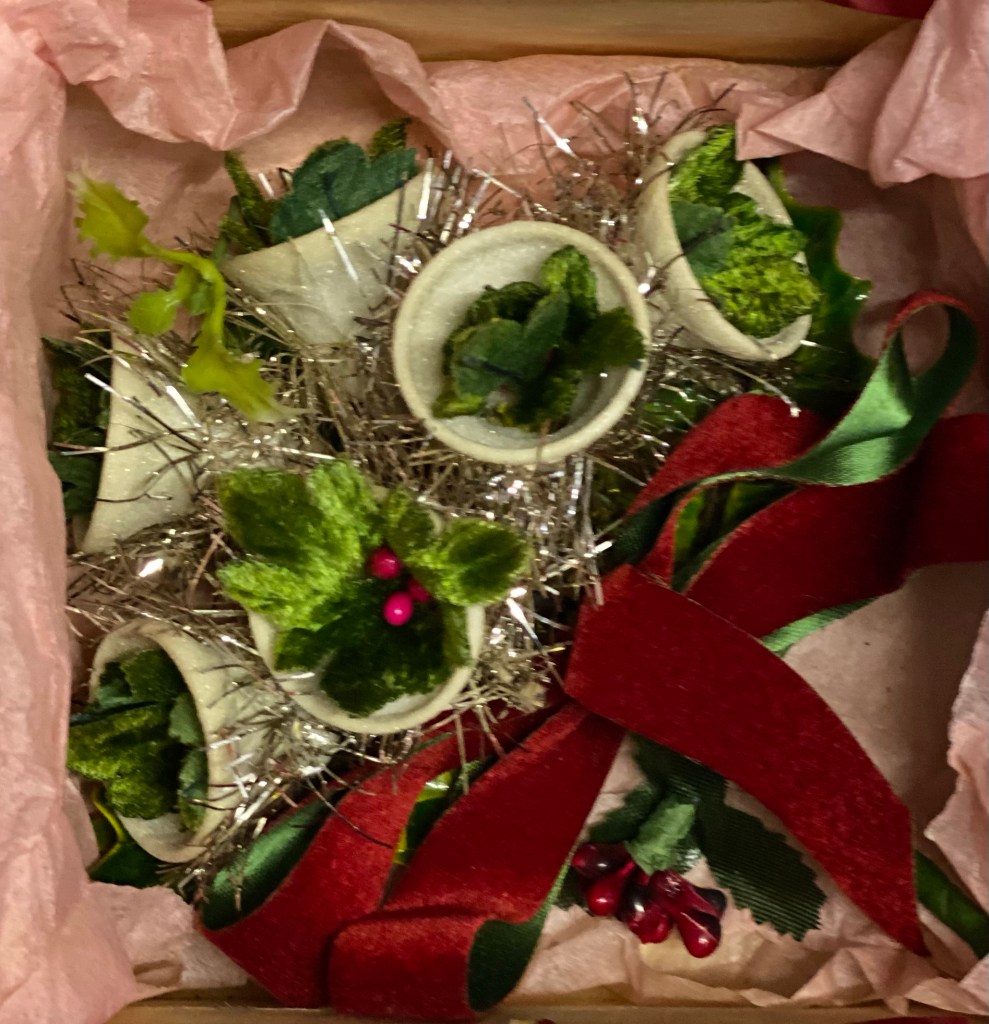

That year, just like every year I can remember, we were off of school for two or three weeks for Christmas break. Before the break, at the class Christmas party, we’d all given Mrs. Peterson our Christmas gifts. The practice in the mid-sixties in the cold, gray, windy midwest, or at least in our neighborhood, was to give your teacher a Christmas corsage; these were pretty, often fake flowers (or no flowers at all, if I remember correctly) and they were adorned with ribbons and trinkets. They certainly were festive. The trouble, as far as I could see at the time, though, was that everyone gave the teacher a corsage. How many dang corsages could one teacher wear? So, I opted that year to give the teacher something else, likely some candy or perfume; it made sense to me, but the gesture did not pass without incurring grief from several of my classmates.

A Typical Christmas Corsage

Over time, I would become more accustomed to classmates wondering what on earth I was thinking. In fifth grade, for example, a couple of us created a class-wide crisis when we did not wear dresses on picture day. Whoa. (Strangely, we were allowed to wear pants in grade school at that school; later, I’d transfer to another town where girls were required to wear dresses, no matter what the weather.) What some of us had figured out, though, was this: when we wore a dress (with nice shoes) for picture day, recess was a wash and we really, really liked running and climbing during recess. In addition, the individual pictures were only head and shoulders so a pretty blouse would serve the same purpose as a dress. Finally, at least in my case, since I was the second tallest kid in the class, I always always stood on the back row for the class picture anyway so no one ever saw what I was wearing. I could see no reason to endure the discomfort of the dress and patent-leather shoes all day when I could be in pants and tennis shoes. Sadly, I had to explain that about twenty-five times that year and, while I was annoyed at that, I was more annoyed at myself for not figuring this out in first or second grade. Still, embracing my generation’s dictim “Question Everything” was a learning curve, and the Christmas corsage might be considered the first volley in my war on ridiculous expectations.

No Questions Allowed.

Still, this post is about war, war and children.

That Christmas break, we went home a happy lot and looked forward to returning in January. When we did step back into that classroom, we did not find Mrs. Peterson at all. What we found was another teacher, an older woman whom I’m sure was a lovely and gifted teacher, but on the first day back to class that frosty January, we were told simply, “Mrs. Peterson is gone and this is your new teacher.” End of discussion. No questions allowed though you know we had plenty. In my child’s memory, our anger and questions were dismissed, sent to the corner, not allowed.

Now, if any of our parents heard about this from us or if any of them knew what had happened or reached out to the school with their own questions, I don’t know. I don’t remember if I had any conversations with my parents about this either. I can reliably tell you that they were not advocates of my budding proclivity for questioning everything.

It would be decades later when some of that memory came into focus for me; I would realize, belatedly, something must have happened to Mrs. Peterson’s husband. Perhaps he was injured, or killed; we could hope, even, he simply returned home to the states and they were transferred or moved. We never knew though and no one ever told us, which meant our imaginations would have been allowed to run wild if it hadn’t been made so clear that there was no room for that. For me, those banished questions would not surface again until, as a Campus Minister, I began working with students who were combat veterans.

(Lazarus Project, which started as The Lazarus Project, became Soldiers And Families Embraced. The free counseling program began in 2010 as a United Methodist Campus Ministry project to help combat veterans and their families who were attending Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tennessee, adjacent to Fort Campbell, Kentucky. By that time, the US had been at war for nearly a decade, but much of burden of fighting was borne by less than 1% of the US population and felt then quite keenly by their families.The program expanded into the entire community as we began to hear from veterans and family members from all eras who needed to process their pain, grief, anger and ask their questions.)

The name “Lazarus Project” was inspired by the idea that when the biblical Lazarus emerged from the tomb he still had the trappings and stench of war on him and the community is told by Jesus to “go to him” and unbind him that he might live again, rather than wait until he asks for help. See John 11, especially John 11:38-44. We started with peer support groups for veterans and their families and evolved into a full-fledged counseling program offering free counseling still to those affected by wars of all eras.

One part of the program for several years involved joint retreats to find healing from war, and one of the first activities in those retreats involved introducing yourself by sharing some symbol of your experience with war.

Back to the Second Grade

As I prepared to go to my first retreat, I was at a loss to share any personal experience with war until I was cleaning out a drawer and stumbled upon an award I received at the end of sixth grade from the American Legion. It was not until I was holding that award that I realized my own experience with war began in second grade with Mrs. Peterson.

It was not until I was holding that award that I realized my own experience with war began in second grade with Mrs. Peterson.

Certainly, this award, which, I was sure was going to my classmate, Karla, did not – in my sixth-grade mind – have anything to do with war.

American Legion Award given each year to one boy and one girl in the sixth grade of each local Elementary school for “Courage, Honor, Leadership, Patriotism, Scholarship and Service.”

Holding it all those years later, however, gave air to a mass of memories. To my surprise, the memory of Mrs. Peterson and her Soldier were near the top. Processing those memories in that retreat, sorting through the confusion and child’s anger, I am grateful to say, helped the Lazarus Project and then SAFE become community educators about the effects of war on children. The first thing we taught was that children DO know about war, whether we adults want to admit it or not, and denying their experience has both immediate and longterm consequences.

Already, one of our first clients for counseling had been an angry child, a six-year-old, who had been expelled from school for stabbing other children with pencils. Her grandmother came to us asking for help. The child’s father had been deployed into combat three times for a year at a time since she had been born and her mother had melted under the stress, grief and fear of all those long deployments. All that the child knew was that now Mommy also had “gone away.” The child was angry and she had lots of questions no one could answer. We learned quickly that she was among the many children of that war and so many other wars who wake up wondering if Daddy was still alive, if Mommy would be able to come home, and if, when they did come home, they’d be “all right.”

“You lied,” he said. “You all lied.”

A ten-year-old client of our program.

One of the saddest days of our program was when a child whose father had sustained a serious Traumatic Brain Injury declared that all the adults around him were liars because they had all told him Daddy would be okay, and he did not need to worry. You lied, he said. Like most of us adults who want to protect the children, the adults in his life underestimated his ability to grasp the seriousness of the situation and discounted his need for honesty and his right to have the chance to grieve the possibilities and air his fears, too.

All of us at Lazarus Project were amazed, though, at how much it helped the six-year-old just to have an adult hear her and assure her that of course she was angry and rightly so. She desperately needed someone to normalize that anger. Being able to ask her questions without upsetting everyone else around her didn’t fix the situation or mean she wouldn’t need more counseling to understand and name her feelings but it did help her stop stabbing other children with pencils. Allowing her space to air her questions likely had the added bonus of helping her process them before they became jumbled fragments tossed into a backpack that might not be opened for decades, if ever.

As the wars continued, more and more resources surfaced to help talk about war with children. Sadly, as those wars continued, there were children who had spent their entire school experience, twelve years or more, with one or the other parent deployed into combat zones. The questions they have and the feelings they need to process will continue throughout their lives.

Our questions don’t always need answers, just air, the air to breathe, the chance to be counted.

As I write this, I think of my granddaughter who is only seven and, while she seems quite young, she does know about death and she has dealt with the losses of animals and people she has known. Thankfully, she is blessed to be surrounded by adults who allow her to ask questions, even if they don’t have answers for her.

It’s not easy to hear her questions some times, but it IS simple. What we are learning by listening is that our questions don’t always need answers; they do need air, the air to breathe and the chance to be counted.