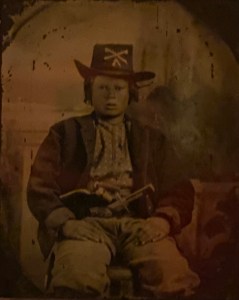

During a visit some thirty years ago, my (now late) grandmother mentioned being descended from French Huguenots. (I had to look them up at the time: A French Protestant movement in the 16th and 17th centuries. Calvinist. Suffered persecution by the religious majority at the time and many thousands of them emigrated from France). Grandma also lamented at the time that very little of her family history was recorded anywhere. Because I was working outside the home then and raising two little boys, I could only lament with her and suggest she record some stories for us on a cassette recorder. She didn’t, though, and now she and her siblings are gone and we have lost most of that history, including any details about our little soldier in the Ambrotype portrait above.

Many family stories today go untold, or if they are told, they have gaps, and placing them in time or understanding the story is tough after all the actors have left the stage. After Grandma died, I could find no one who knew anything about Huguenots and a family connection. No one was left to rebut the rumors of our being related to President Grover Cleveland (because Grandma’s family name was Cleland, not Cleveland, that is highly unlikely.) I had known through my research that she was a cousin of Black Jack Pershing, but we had not talked about any of this and now we cannot.

Grandma lamented once that she possibly was descended from the author of the Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, an erotic novel that led to the arrest of author John Cleland in 1748. This particular piece of history especially mortified Grandma, which is sad because it is likely accurate, and I would love to know more about how her parents and grandparents felt then, too.

Most of my family history though has been learned through online research, which means that by itself, it is just the list of ancestors with little of the background, the scenery, or the props and, of course, no narration. The result of relying only on such research is that we get just enough of several of the stories to need and want more – context, detail, resolution – but, again, because the principals were gone, we are left to research and then try to fill in the gaps, leaving many of these rich stories to be lost forever. Needlessly.

Too many of these rich stories are lost forever. Needlessly.

I once even learned from online research that I had a great-grandmother who was alive until I was fourteen and lived an hour away, but I never met her. When I asked, I was told, “We didn’t like her very much.” I was stunned at the time and now of course totally regret that I did not press the matter and ask about what had happened, did not seek the story while there was a player still around to offer some narration.

Turns out, I’m not alone. Elizabeth Keating, PH.D., is the author of The Essential Questions: Interview Your Family to Uncover Stories and Bridge Generations and writes about the loss of these stories:

“The people I interviewed knew so little about their grandparents’ or parents’ early lives, such as how they were raised and what they experienced as young people. Few could remember any personal stories about when their grandparents or parents were children. Whole ways of life were passing away unknown. A kind of genealogical amnesia was eating holes in these family histories as permanently as moths eat holes in the sweaters lovingly knitted by our ancestors.”

Asking family members for family stories ought to be quite easy and entertaining but that doesn’t seem to be the case in our media-saturated world.

The good news is that we can use our online research and our boxes of pictures to start the conversations. Keating gives lots of examples of what to ask to flesh out your family’s tales. If there are still older family members alive, starting the storytelling can be as simply as carefully studying some of those old sepia tone family portraits.

On my father’s side of the family, most of the stories I’d learned were from online research until the day his sister asked if I’d be interested in a box of old photos. That cardboard box was a treasure chest of stories about tumult, typhoid and the kindness of strangers. The next time I saw my aunt, I came to the conversation with some specific questions and a vague feeling about why two photos in particular made no sense to me.

The photos set her memories flowing and one story in particular that she remembered as being set in the Depression but, we soon realized, could not be the case. Certainly the family, like many in the country, lived with few creature comforts even before the country was plunged into a depression. Indeed, pretty much everyone spent their lives at the mercy of the elements, epidemics and accidents with little modern health care and only the food they could plant and harvest, hunt or gain in a barter.

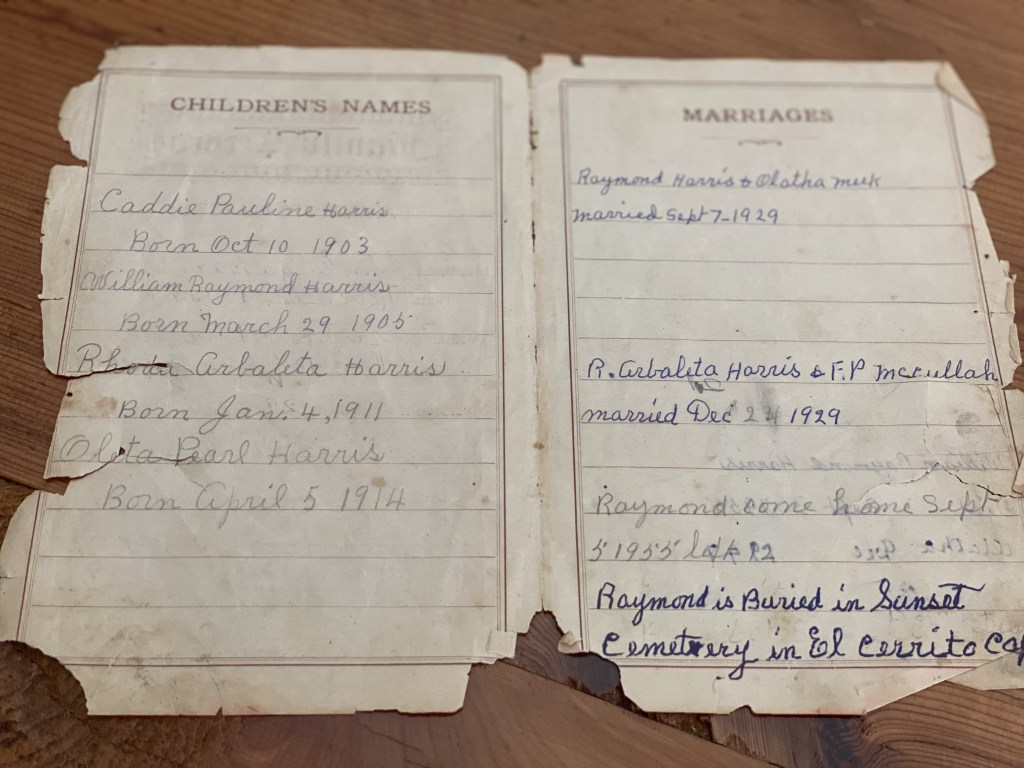

My aunt knew that the father in the family was out of the picture; he would die in a sanatorium with tuberculosis. So, at the time that this story begins, my great-grandmother was running a small farm with her children, whom records indicated were born in 1903, 1905, 1911 and 1914. My grandmother was the one born in 1911.

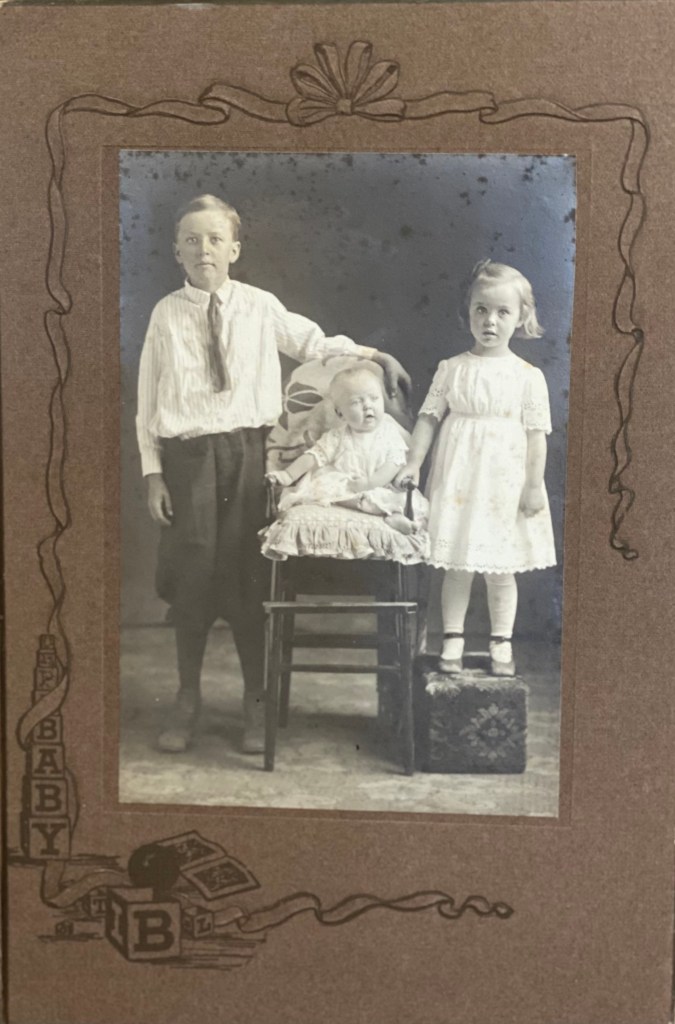

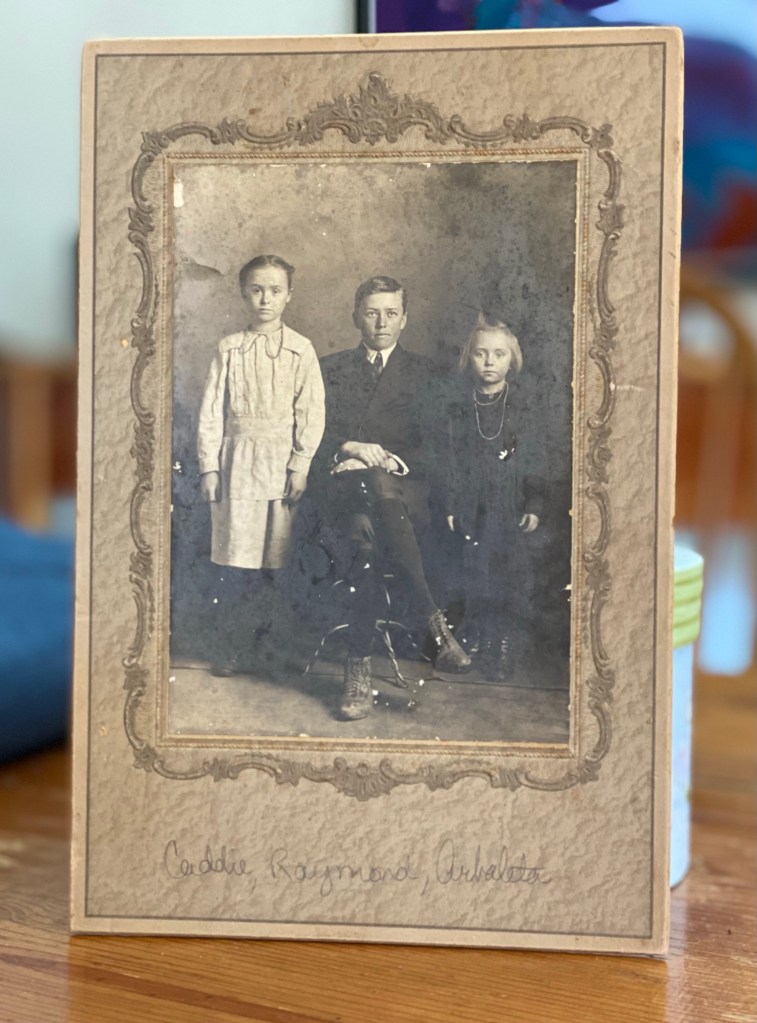

The children’s pictures below, shared with me by my aunt, were what directed my questions and, eventually, led her to remember and share the story of what she called “the family’s angel.” The configurations simply made no sense to me.

The first picture is of her (and my Dad’s) uncle Raymond (born 1905), with baby Pearl (born 1914) and my grandmother, Arbaleta, born 1911. That picture would have been taken after 1914, obviously. Love the box Grandma is standing on, by the way. The second picture would have been taken later, with Grandma Arbaleta (standing,) then Raymond and then Pearl. Even though the picture to the right says it is Caddie on the left, actually she is absent from either picture. Caddie, their older sister, was born in 1903, but died 1909. We found no pictures of her. Had she lived, there would have been a girl taller than Raymond in the picture to the left. Okay, that mystery was solved. Still, something was off.

We turned to the rest of the the dates recorded in the front of the family Bible and my aunt was reminded that Pearl also had died young, and that particular tidbit of information started the memories swirling. Her memory of what happened to Pearl is the real treasure here: over the next hour, she told me about how a stranger, an “angel,” she said, kept the family together in a time that could only be described as bleak.

Evidently, Baby Pearl, (in both pictures) died in 1923 at age nine when Raymond was 18 and Grandma was 12. Their father had died three years earlier, and a typhoid epidemic took Pearl and made their mother, Mila, deathly ill.

Things would have been rough enough since Mila was trying to keep a small family farm going even before the typhoid epidemic hit the area. When Pearl died, the fact that their mother was near death meant Raymond, 18, and Grandma Leta, 12, were left to do what most folks did back then: they had to prepare their sister’s body to be buried. Few could afford for an undertaker to come, so, typically, a coffin would be built by a friend or relative and then it would be laid upon the kitchen table so the family could prepare the body to be buried. As I sat there listening, I could not imagine how tragic and overwhelming it must have been to have a coffin for a sister laid on the kitchen table before me. I could not imagine taking a cloth and soap and water and preparing the body of someone I loved in order for them to be buried. Worse, in this case, though, was that, because the mother was so ill, two coffins were delivered, one for the little sister and one for the mother who was expected to die soon.

The future for these two siblings looked pretty bleak, too. They likely both wondered how they’d manage, once their mother died, and how they’d find food, or pay for oil or firewood. We’re not aware if Raymond was working or at what at the time, but, for the time being, he was tasked with keeping things going and caring for their mother as well. It must have been somewhat overwhelming, but, the story goes, one day, a stranger happened by. Travelers often stopped at farms then – there were no gas stations or Cracker Barrels – and even before the Great Depression swept across the nation, it was not at all unusual for a stranger traveling through to stop to ask for a bite of something to eat or offer to work for a day to earn a meal and a place to sleep.

Such a traveler evidently stopped into the home of my great-grandmother Mila as she was dying of Typhoid and offered to help this young boy and girl keep the farm going. Perhaps this traveler was even hoping to stay after Mila died.

Can you imagine standing outside the door, being told there was typhoid in the home but being so tired, destitute and hungry that you would offer to stay anyway if it meant some food for a few days? Who knows, maybe he thought, “Either I’ll be spared this illness and have found a new home OR I’ll die soon.” Evidently it was worth it to him because this stranger stayed. He helped the two teens keep the farm running, helped them bury their little sister in the church cemetery and made sure they had heat, the occasional hamhock and hope while they cared for their dying mother.

Turns out, though, Mila, my great-grandmother didn’t die. Instead, she began to recover, and once she was able to be up and about, the traveler took his leave. When my aunt shared this rather miraculous ending, I hoped she also would share what happened to the traveler, but, alas, she said, we don’t know his name; that piece of the story was lost.

All that my aunt remembered was that the children had a stranger willing to help to keep things going and, because of him, the family stayed together and kept the home. I’d love to know more about this stranger, this “angel.”

I encourage you not to rely simply on genealogical research if your desire is to know your own family’s stories. Such research is a great start, but it’s a little like being online friends: the tendency is for there to be very little face to face time or conversation, and, in the end, what you have is a more shallow, less meaningful, sanitized experience. Your interaction might be safe but not necessarily satisfying, like the “hug” emoji in place of a real hug. If you want the story, the real hug, you need to sit together and ask specific questions – about social interactions, treasured possessions, popular culture when Grandma was young, and how these all changed with historic events or her own life changes, for just a few examples.

What did you have to do to get your picture scratched off of the family record?

Of course, this is risky since the feel-good miracle stories often are right next to the bitter ones in the picture box. Potentially huge clues to family history can be found on documents that still exist but have been angrily altered like the photo below where some family member’s face has been scratched off. In a time when having even one portrait of yourself was a true luxury, and often that picture is the only record of a family group, what did you have to do to get your picture scratched off of the family record?

In the book, Keating argues that sometimes this kind of research is touchy but NOT asking just perpetuates the pain. She talks about her own family stories and the questions she didn’t ask of her mother, for example: “Before she died, I—like many children, I suspect—avoided any potential clashes, wanting to preserve harmony rather than ask sensitive questions.” (Keating, Elizabeth. The Essential Questions, p. 2. Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.) Take the chance, she suggests, to avoid regrets.

Finally, Keating asks and I would ask too: what do you wish people knew about you? That question is one I ask myself as I write this blog. I think especially of my children and grandchildren and want to offer them some of the stories we have not shared before now. While on the one hand such explorations can feel selfish, I know how much I wish even one of my grandparents and I had sought the answers to these questions while we still could.

Go then.

Ask.

Ask specific questions.

Ask them to tell you what you don’t even know to ask. Maybe you’ll find your Huguenots before it’s too late.