I come for the cookies….

“Why,” I asked the woman seated next to me, both of us with arms outstretched being squeezed by thin rubber tourniquets, “would someone go to the trouble of giving blood to that venerable institution called the Red Cross expecting that their blood would be rejected?” I kept my eyes trained on hers to avoid witnessing either needle being inserted, grateful for the distraction.

“To see if they’re still clean,” was the answer she gave that summer afternoon in the Red Cross’s makeshift donation center in our little town’s City Hall. From the looks of it, the BloodMobile staff had the travel and setup routine down and, on this particular afternoon, business was booming in that air-conditioned meeting room. Word was out and neighbors in the Highland Rim town of Portland, Tennessee, population just over 5,000, were lining up, enticed perhaps by some visiting and sharing of the cookies and orange juice handed out to donors, all playing out indoors where there was air that you could breathe in August. The tech loosened the rubber tourniquet around my arm and the young woman in the next chair leaned over and explained. “If you suspect you have AIDS, you can let the Red Cross diagnose you. They’ll only use your blood if it’s clean,” she said. “Lots cheaper than paying for a test. And no one asks you questions you don’t want to answer.”

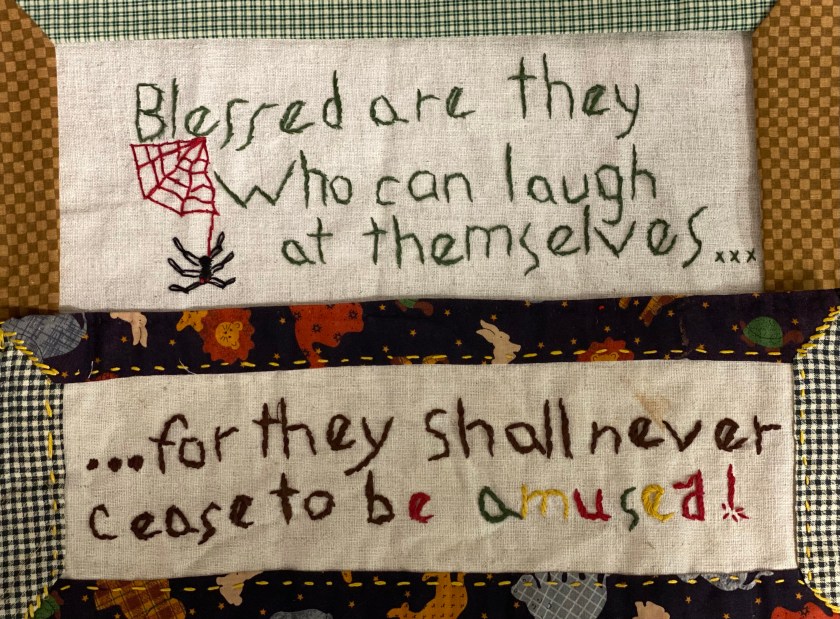

Plus, there are cookies.

People amaze me. I sat back as the blood flowed and reviewed how creative types could see what the rest of us cannot, who find ways to work around existing services to fit their needs, even if the services were not intended to diagnose, for example. These workarounds can be quite ingenious, but less about artistic visions and more often the child of necessity. Were folks adapting the services of the Red Cross the way others did those phone hotlines, I wondered? The ones where you could find someone to talk to you for free? Maybe not, I thought, more like 2-1-1. Used to be, if you wanted to talk to someone but you don’t want two police officers showing up at your door to do a “well check,” you could dial, or rather, punch in “2-1-1.” The idea washed over me that our culture used to, at least, have a number of systems, screenings and alert systems apparently in place. Some were designed to separate the lonely from the disturbed, some alerted us when we needed to see a doctor, still others, a process of interest to me at the time, offered to determine if you were among the “called” or simply delusional. As someone whose life path led me into ordained ministry by way of teaching, social work and writing, I was becoming familiar with this web of services.

You’ve Got a Friend….

I was serving Neeley’s Bend UMC by this point and our proximity to Nashville meant we had access to a 211 directory. Our little town of Portland, nearer the Kentucky state line, where my son and I still lived as he finished out high school, did not have such service, a system where anyone could call and chat with another, live person for a bit at no cost and about pretty much anything. Designed to help steer local residents towards food pantries or accessible ride programs, the lines were answered by folks who became, at least for a while, the only friends some could claim. Turns out, lonely people were also creative and many of them figured out they could call every day. In fact, lonely callers so overwhelmed the 211 system that a few rules became necessary: callers were limited to one call a day per person for a limited duration. Rules ruin it for everyone, some lamented, but, then again, even if only for ten minutes a day, you still had a friend who’d listen to you, for “free.” No strings attached. The beauty for many was that there was no real effort on the caller’s part except to dial the phone; no quid pro quo was necessary and no relational reciprocation was required. Someone was always at your (beck and) call. At least once a day. Whether we were annoyed with the smell of our pet’s kitty litter or the price of avocados, we could talk to a person through 211 about anything for ten minutes and they’d listen. They could even tell you where to get free groceries and usually there’d be cookies. All for free. Not sure how many towns have those systems in place now, but they definitely serve a purpose.

Along the same vein, (pun intended), while I sat in that chair watching the bag fill with blood, I had learned that, if you believed God talked to you and you wanted to know if you were sane, there were workarounds; in particular, there were helpful gatekeepers. While some folks slide easily into ordained ministry, others of us step onto the path shakily, unsure for ourselves and aware that those around us will be more than a little skeptical. For me, the first step was admitting to my husband that I prayed. We had been married more than a decade when I sat on the edge of the bed we shared, clutching a lumpy pillow, cringing as I told him that swearing was not in fact the only time I used the word “God” (with a capital ‘G.”) This was the man who was outspoken about his belief that only mental weaklings believed in a deity of any kind.

God talks to you?!?! Of all people…?

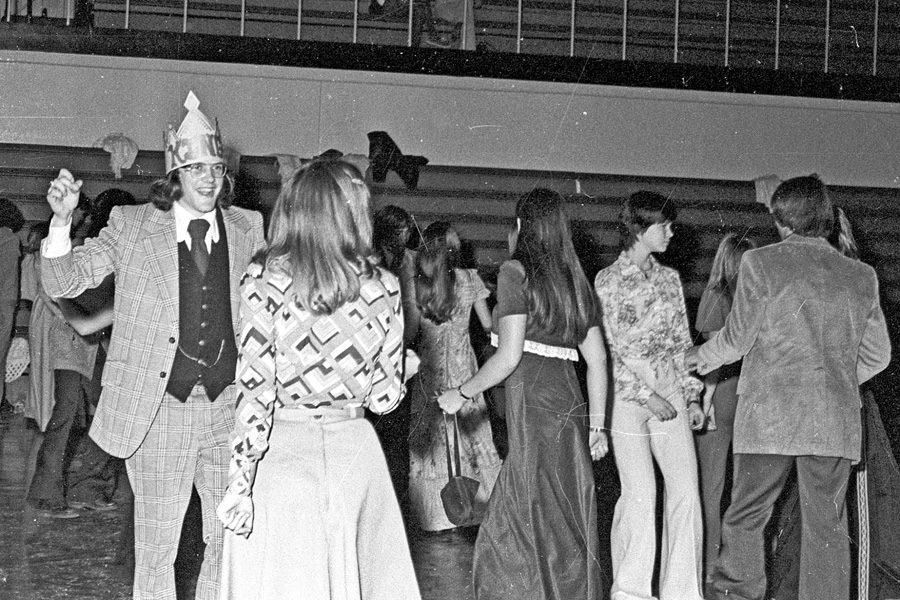

For years as a teen, long before I’d met my husband or considered turning to the church for a vocation, I had struggled with anxious thoughts, worries that felt like there was one of those old mimeograph machines in my head. Perhaps you are old enough to remember those: the kind with the drum that you cranked by hand while the paper revolved around and your words were printed on multiple pages, the precursor to a copy machine. For most of my life, I’d been trying to make decisions absent any sage advice from my parents who, when approached for advice, waved me and my siblings off, annoyed, as if to remind us they were overwhelmed enough already by our existence and life in general. My father once described to me his own anxieties by sharing that he had spent most of his adult life feeling like he was hanging dangerously onto a ledge and, above him, people were constantly stepping on his fingers to make him let go, give up, go away. He could offer no guidance or help to anyone else while he was just hanging on.

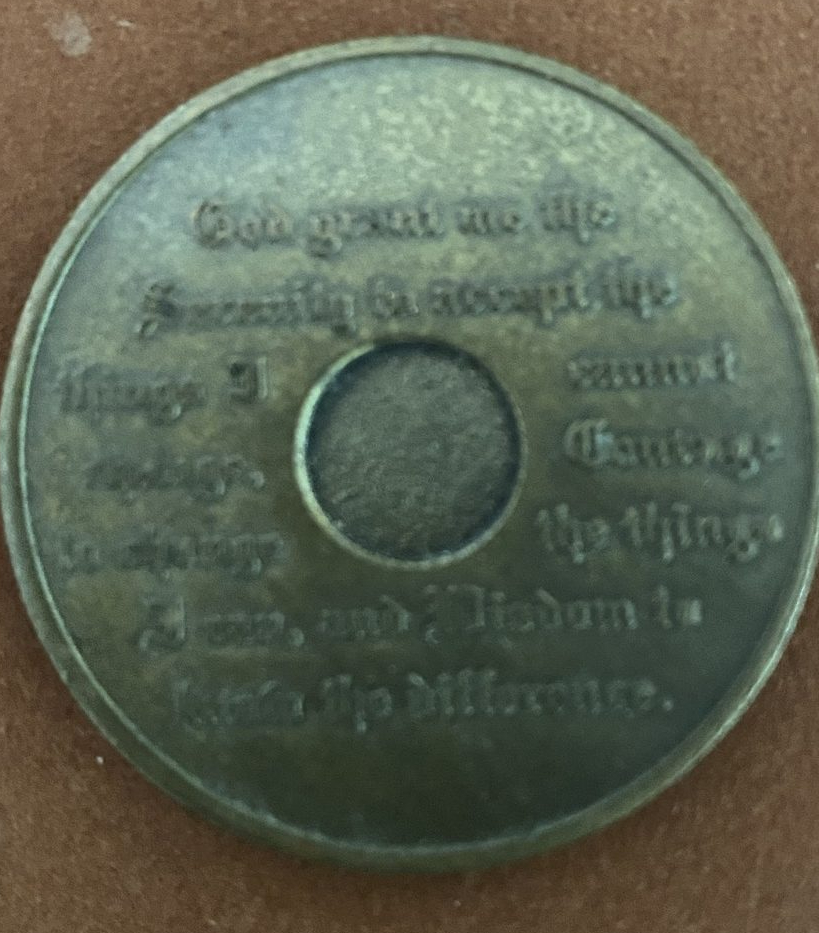

“God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can and the wisdom to know the difference.”

On occasion, because of my own anxieties, on the mimeograph machine in my mind, it seemed like a couple of pieces of paper would come loose and flap wildly as the drum turned. My mind was that drum and my thoughts were that paper flapping uncontrollably. I had tried a variety of ways to ease my anxieties: visualizing silly images like a cat with a stop sign attached to its tail or locking my worries in a dumpster, but nothing helped much until I found my way into an Al-Anon meeting one day. I was nineteen and dating David, a man who shared early on that he was a member of Alcoholics Anonymous and, who, after having known my mother for a few weeks, thought he ought to tell me about Al-Anon. “I don’t know much about that group except they used the same 12 Steps we use in AA. Who knows? It might just be a lot of old women complaining about their drunk husbands, but it’s there and worth a try.”

You could always try those meetings….

He shared this one morning over coffee; I’d sought him out, distraught after encountering my mother drunk that morning. His suggestion hit me at the right moment and I found a meeting that evening at the back of the small storefront where the AA meeting was held. I was too worn out with navigating the alcohol and moods to be nervous about walking into a room where I knew no one. What happened then was that I walked into a roomful of loving, wise, patient surrogate parents who shared with me the Twelve Steps. Members of Al-Anon are, like me, those who have lived with or currently in relationship with alcoholics. The first three steps to that philosophy are designed to help you recognize that your life is unmanageable; likely if you grew up in an alcoholic home, your life had always seemed pretty unmanageable. The Third Step talks about believing in and trusting that there was a God and that God could help. The idea of letting go of control of my life seemed dangerous but I kept going back and sharing how stressful and chaotic my family’s day to day life was. My own life at that time was a mess as well: I couldn’t tell you what I believed or what I needed to do for my next job, let alone as a career. So, per their suggestion, I attended 90 meetings in 90 days, letting those people love on me and studying the Steps. In contrast to everything around me, the Twelve Steps were not chaotic, but rather offered a different way to make decisions and live life. Then, one afternoon, I was curled up on my bed, emotionally exhausted and lost. It seemed a voice in my head, a benevolent voice, said, “You just need to sit down and shut up.” Suddenly, it felt like I was not alone in making decisions. I took a breath and stopped asking myself or God or anyone who’d listen; I just sat quietly, suddenly reassured the answer would find me if I sat still and waited. A revelation. There would be more. Eventually. I stopped dating David, but I kept coming back to the meetings regularly for nearly two decades, wherever I lived, and I know that that program and those people saved my life and even helped me grow up, at least a bit.

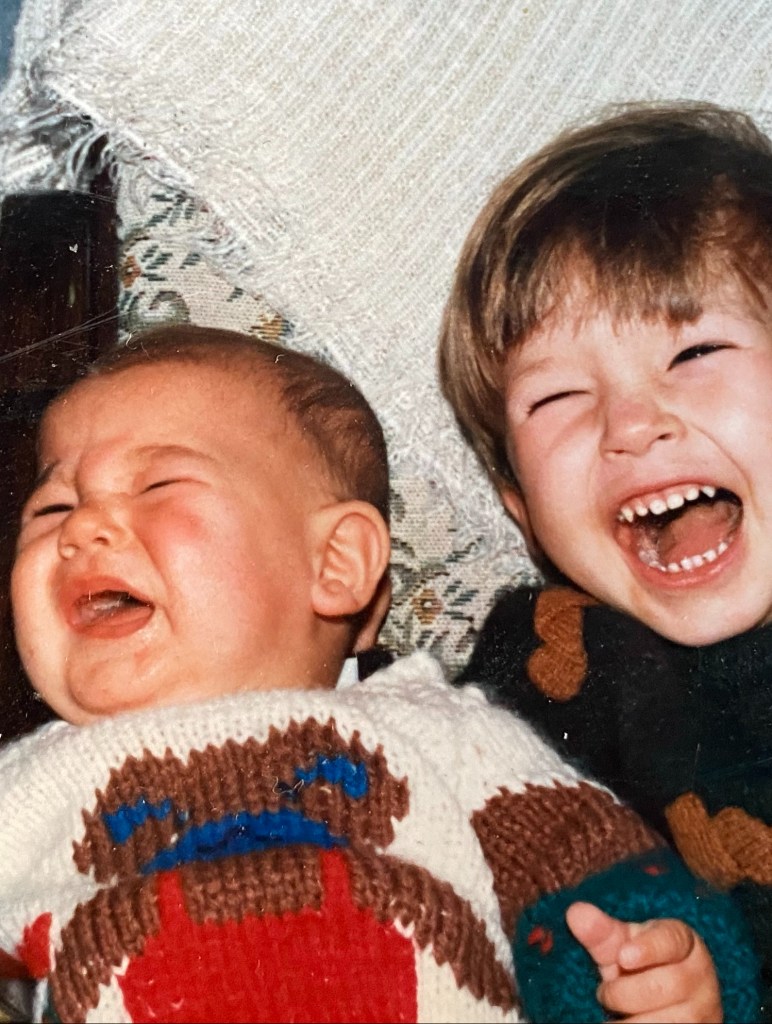

A decade later, married and teaching with two small boys, I finally told my then husband that I prayed and, when he didn’t laugh at me, I admitted that God not only talked to me but that I believed I was meant to be involved full time in some ministry. You might think that everyone around you would celebrate if you announced your call to church ministry, and that’s true in some circles. I’d been attending a Methodist Church regularly with our sons, but most of our friends at that time were not attending any church; most were agnostic at best. Thus, I felt the need to be selective when telling anyone that I had regular conversations with God, even those that are only in my head. It didn’t help that God and I were negotiating what ministry for me might look like and I was still quite leery of admitting God wanted anything from me, of all people. If nothing else, at the time, I cussed like a sailor. I had to wonder how that would work!

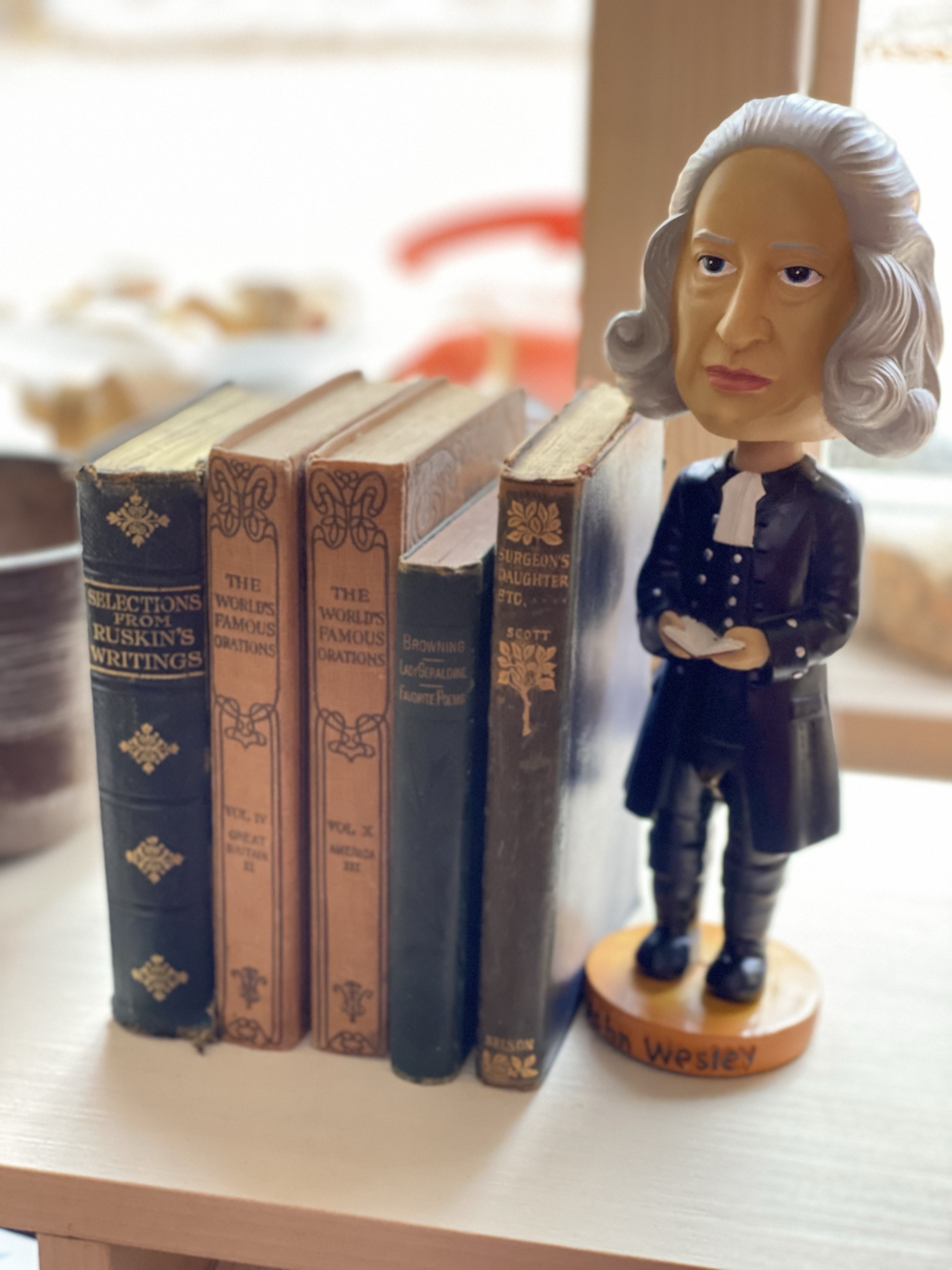

Moving forward into what would become an increasingly complicated path towards ordination, it was clear that I had to be subtle about my next steps, and at least appear sane and convincing enough to be taken seriously. The first step was to write a letter to the Methodist Superintendent of the district I lived in and declare my desire to “explore ministry.” Somewhere in there, it was necessary to admit publicly – to say out loud in front of others – that God spoke to me and told me that I was “called” to ministry. Another chance to cringe.

My First Church

The process of moving towards ordination (in the Methodist Church at least) had certainly been more involved than dialing 211, but it was not dissimilar. I’d written that letter and one of the first things the church did was assign me someone to be my mentor, someone who would listen to me and ask lots of questions. Kind of like a free friend, but with a purpose. From then on out, as I went through the process, there were plenty of folks who were ready and willing to swim in the deep end of thoughts and emotions with me, like those free friends, or better, like counselors I didn’t have to pay. The first thing they did, though, was send me to a psychologist’s office because there was a test in my future. Not free, I remember thinking, but a whole lot less dramatic than calling the local hotline and telling them I talk to God, I guess.

The psychological exam was just one of the many steps involved in becoming a Methodist minister, a process that is quite long and involved, and can become expensive for many. I had to laugh when I found out, though, that people also used this process, or at least the psychological testing, as a workaround for their own mental screening; it wasn’t free and was far more involved than a simple phone call. I had to wonder: Did they want to be stopped before they hurt someone? I remember sitting in a leather chair in a paneled office with a massive wooden desk between me and the psychologist. I will be forever grateful he started the conversation with, “First, your test reveals you are mentally strong and resilient. All good.”

Relieved, I sat back in the leather chair, and let out a laugh, then admitted, “I’ve got to ask about one of the questions in that test.”

“Sure,” he said.

“It was something like, ‘Do you like to smell other people’s shoes? Do some people actually admit to enjoying aroma of another person’s shoes?’”

“You’d be surprised,” the psychologist said.

“Why on earth would you do that?”

“It’s a way to ask for help, ostensibly without actually asking. They want us to catch them before they do something dangerous,” he explained.

I sure understand that, I thought, making a mental note to be, as a minister, more focussed on the reasons behind those workarounds than the tricks themselves. The reasons were where ministry would happen, I realized. Sometimes people need someone to help them figure out if they are crazy because they talk to – and hear from – God. Just as often, though, folks need to be encouraged to share what they believe God is telling them. Walking people through that process for the United Methodist Church requires years of discernment, writing, interviews and 84 hours of seminary. In other churches, you simply walk up to the front of the sanctuary and declare that God talks to you, indeed, that God is calling you to ministry. I get why it’s so tough to get through the ordination process for the UMC, though, and, don’t get me wrong: I respect it. Even after all the schooling and the discerning and retreats and writing and interviews, after all that I learned about myself and about ministry, I still stood behind the pulpit of my first church and wondered if I was in the right place. I suspect though that God is more able to use us when we are not so sure of ourselves, when we remember we need God. And, my experience has been that, often, we learn we need God through recognizing we need one another, whether we find one another through a phone call, a church or a self-help meeting.

Sometimes, in perverse moments, though, I will admit, I’ve wondered if we don’t just need to suggest people start with dialing 211. It’s a whole lot faster and cheaper and they will even tell you where to get free cookies.

Leave a comment