There’s an often told Chinese story, “Good or Bad, Who Knows?” about a farmer, his son and his horses. The farmer used an old horse to help plough his fields, but one day, the horse escaped and galloped off. When the farmer’s neighbors offered their sympathies to the farmer over the bad news, he simply replied, “Good? or Bad? Who Knows?”

As it happens, a week later, the old horse returned and brought with it a herd of horses! This time the neighbors congratulated the farmer on this good fortune. Once again, though, he replied, “Good? or Bad? Who knows?”

As it happens, a few days later, when the farmer’s son was attempting to tame one of the wild horses, he fell off the horse’s back and broke his leg. Everyone thought this was very bad luck. The farmer’s reaction again was, “Good? or Bad? Who knows?”

Some weeks later, then, when the army marched into the village requiring every able-bodied youth they found to enlist, they found the farmer’s son with this broken leg and he was not drafted.

“Good? or Bad? Who Knows?”

Banner Week? Week From Hell? Who Knows?

It was a banner week. Or the week from hell. Depending on when you asked me. Start seminary. Check. Get divorced. Check. Buy a house solo. Check. In one week. Ugh. Scheduling all three in one week had not been my choice: the seminary starting date was set, but the other two were simply the luck of the draw. I agreed because I wanted to be done with those moments where legal experts, signatures and explanations of terms and fees were laden with shame. Time to move forward.

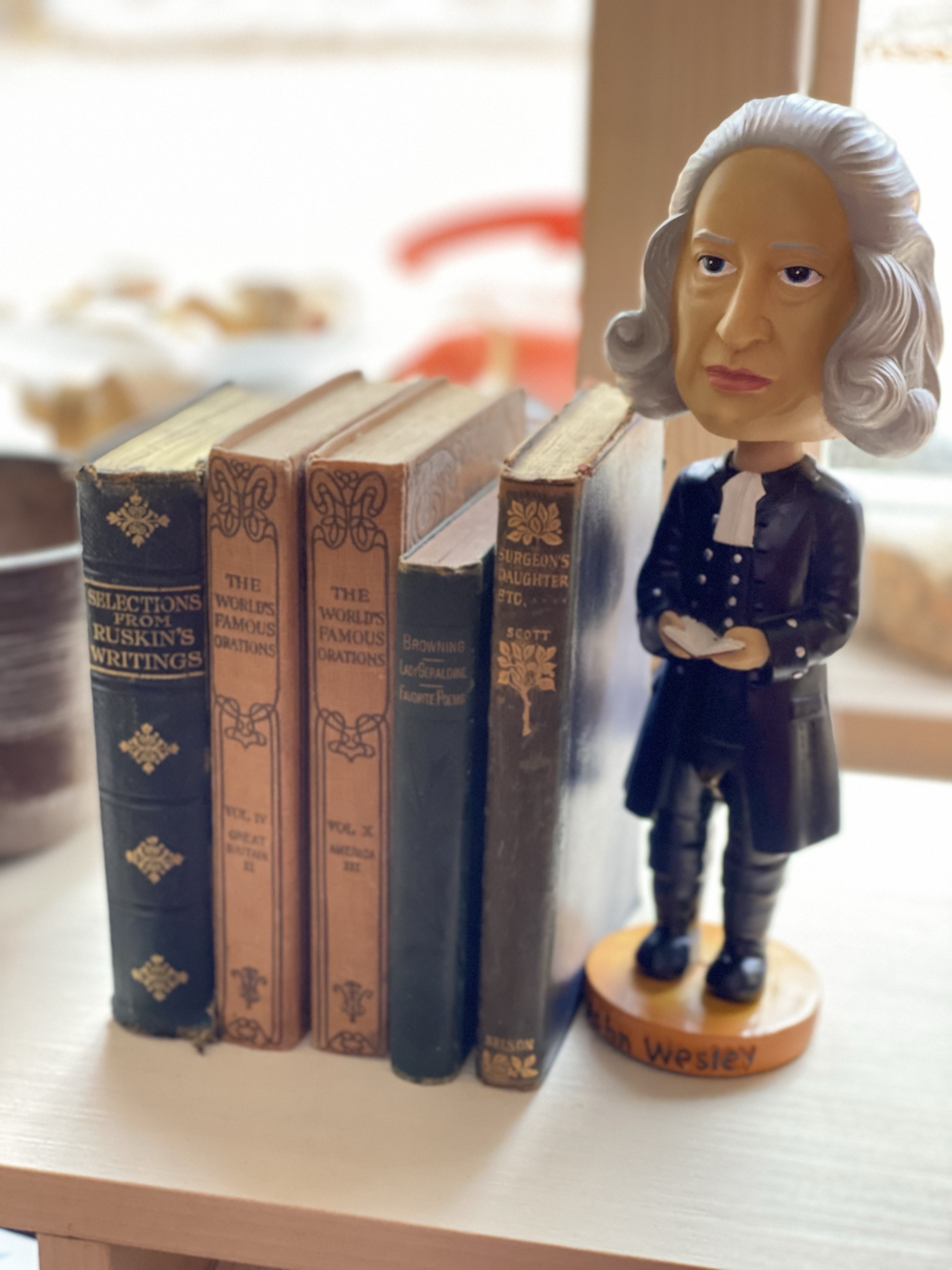

Thus, on a Monday morning in 2003, I began what would be a four-year run at Vanderbilt Divinity School, one of many steps to ordination in the United Methodist Church. I had already been serving as the pastor at a small United Methodist Church. For seven years, I’d been what the UMC calls a Local Pastor, meaning I was the only pastor for that congregation and licensed (given authority) to preach, teach, marry, bury and serve communion for that congregation. During that time, I attended classes offered by the church but all the while I was waiting until my sons got a bit older before entering seminary and moving closer to ordination. I served at Wartrace United Methodist Church in Greenbrier, Tennessee, while living in Portland. Portland, Tennessee, lies about 30 miles from the church to the west and nearly 45 miles north of Nashville where the school is located. For those four years, the daily trek between the three locations would be my own little Bermuda Triangle, and I would clock 40,000 miles each year, though God knows I hated driving.

God also knew that, when I was called into ministry, one of my biggest concerns was that I swore “like a sailor.” How’s this gonna work I wondered? God held my tongue, though, and miraculously, only one time did an obscenity escape my mouth while I was in front of anyone in more than a decade. (I’m gonna blame campus ministry and later working with combat veterans for my language eventually going south again.)

Back to that week. I started seminary and the daily drive back and forth forth and through the back roads. I also would close on a house on Wednesday of that week, my first solo home purchase. Though my husband and I had bought two houses together, I still found the process baffling on my own. With the help of a patient agent, I got there though and much to the relief of my youngest son, we were staying in our little town which meant he could finish high school with friends. More importantly, at least to him, we weren’t going to live in a trailer, apparently a fate worse than any other his teen brain could conjure.

I closed on this house alone on Wednesday after classes because the day before, somewhere in the midst of visits to shut-ins or the hospital and more orientation for my new Vanderbilt classes, I went to court to finalize my divorce. The court appearance was still required then and ours was early in the morning on that Tuesday. I drove down the ridge and sat in the courtroom as the judge appeared and called couple after couple to stand before him to ask if either had any other concerns or if they could agree to the final settlement.

Couple after couple said yes. Some answered quietly and sadly. One or two barked their answers as they stared at their soon-to-be exes. We were last except “we” weren’t there. The judge moved the process along fairly quickly so it was only 9: 15 or 9:20 when our names were called, but my soon-to-be ex was nowhere to be found. I went before the judge, wondered a minute or two whether or not I could change the agreement since my husband wasn’t there yet, then answered. “Yes, I am in agreement to the terms we negotiated with the help of a mediator.”

And then I was divorced. Something I’d never believed I would be. My parents were not happy together, but they stayed married. His parents struggled too but they also were still married. I had never imagined myself divorced. Of course, I never imagined in my forties I’d be preaching or attending seminary and studying theology and Bible and the elements of worship or prison ministry, either, but there I was in classes 9 a.m. every day of the week suddenly. Even nine years earlier, it had not yet entered my mind that I’d be standing in a pulpit trying to help a congregation feel closer to God OR divorced OR buying a home as a single mom. I answered yes, the gavel hit the wooden block on the judge’s bench, and we were done.

Wartrace United Methodist Church was approaching 150 years old when I went there in 1996 and the photo at the left is in front of the original building, taken around the turn of the last century.

I next saw my now ex-husband again as I walked out of the courthouse around 9:30. He was just then walking in a bit late even though he lived in the same town as the county courthouse. I had driven some thirty minutes down the ridge to get there.

“Are you here alone?” The judge had asked me before declaring us divorced.

“Yes, sir.”I had said, “It’s appropriate,” I explained, “It didn’t feel like he showed up for the marriage so I guess there’s no reason to expect him to show up for the divorce.”

The judge frowned, but declared I was no longer married to the man I’d expected to live with forever. I used to tell friends I imagined fondly the two of us walking hand in hand when we were elderly. Perhaps he’d wear a beret; I’d once seen an elderly couple walking together and the man wore a beret. They seemed to walk as if that was simply the most natural thing in the world. The two. Together.

We’d walked through life together but, ironically, we had never actually taken many walks together until our twentieth year of marriage when we were in counseling and needed to talk out so much. The only reliable privacy we had was to go for walks in the neighborhood so we could talk, or argue, without our sons needing to hear it all. I lost about twenty pounds that last year from stress and walking. I’d love to say I never found it again but that’s a different post.

I stopped briefly on the steps leading into the courthouse as my now “ex” husband entered, looking at me quizzically.

“It’s done,” I said, and he frowned.

“Do you want some coffee?” he asked.

My turn to frown. “Pass, “I said. “Heading to class.”

“How’s that going?” he asked, He’d finished his own doctorate while we were married and was none too happy to be paying me alimony while I got my Masters of Divinity, but he also liked academia and worked in it, so he was happy to chat about that if I wanted. I didn’t.

My day would be filled, thankfully, with the business of becoming a Vanderbilt student, and the myriad tasks that entailed would keep my mind occupied that day, I hoped. As soon as I got in the car, though, I wondered if I’d missed a chance. I should have planned to meet up with a friend and get drunk or find a rebound relationship or get a tattoo, I thought. Was I missing out on the chance to be self-destructive and not be judged? Damn.

I drove silently to the campus for more paperwork. Classes began on Wednesday and honestly, at the time, it felt like they would be a welcome relief. Before that, there were school loan papers to sign, books to buy, an ID to be photographed for; time to don my student pastor identity. Orientation day at Vanderbilt Divinity School was, of course, as was the entire week, played out in the muggy heat of August in Tennessee. Sadly, that all required I move about the campus in the heat dressed as a professional without looking wilted. Complicating the day for me was the layout of the campus with the walks between buildings. Those walks meandered through the beautiful campus, but not in any grid-like pattern. While pastoral on cooler days, the campus on that steamy day seemed to confound me every time I had to leave the Divinity School quad to visit another building. The paths between buildings curved and intersected and wound around various statues and even the stone crypt of Bishop William McKendree, who, I would learn, was the first Methodist Bishop born in the USA and credited with establishing Methodism on what was the western frontier in the early nineteenth century. McKendree UM churches dot the countryside in Tennessee, Kentucky and Missouri. He died near Nashville while visiting family and in 1876, his remains were interred in the grounds of Vanderbilt University, along with those of other Methodist bishops, in part because the school originally was created to help educate Methodist ministers.

View of the gravestone of Bishops McKendee, Soule and McTyeire, and Amelia McTyeire, Chancellor Garland, and Dean Thomas O. Summers in 1925. Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives photo archives PA.CAF.GRAV.002 (https://www.vanderbilt.edu/trees/mctyeires-grave/)

Pastoral, bucolic, flowering garden beds sat next to benches that encouraged rest and beautiful old stone buildings invited meditation, but those paths seemed designed to confuse me even though I had grown up reading maps. My father, who helped survey the paths for hundreds of miles of Missouri state highways, taught us how to read maps early, and every year at Christmas, he presented us each with the state highway version of “bling,” a new, revised state map. I was always particularly gifted at directions and maps; I corrected pathways to destinations regularly. It was a gift that I could tell you how to get “there.” Not that day, though and not in that place. The Vanderbilt campus walkways, I soon discovered, curved and meandered enough that, on at least three trips on that sweaty afternoon, I wound up at the wrong building in spite of the decorative campus maps posted prominently. I guess the designers felt students needed to be lost more often. At one point, after finding my campus mailbox, I followed a group who all said they were looking to get campus ID’s next. One by one we got pictures taken and laminated. Mine was a witness to my defeated state on that afternoon. Perspiration matted my hair and my cheeks were red from the heat. The bad news was no one would recognize me in that picture. Perhaps that’d be good news one day. My query about retaking the photo on another day was met with a glare. The clerk was spending her afternoon in the air conditioning, I thought. What’s her issue?

I moved along, aware a library card still needed to be acquired and a locker in the Divinity School building as well. If I could find the library, the Divinity School would be close, I reasoned, but the heat was getting to me. At one point, I stopped into the food court to find some lunch but found the choices bewildering and the process moved more quickly than I was prepared to navigate. Students who’d only recently attended undergraduate classes jostled me and moved around me and the hot food worker glared until I took my tray and moved to the salad bar. A few minutes later, I stabbed at my salad and wiped the sweat off my forehead trying to unstick my bangs. As I dabbed at my sweaty forehead with a napkin, another worker, a woman, stopped at my table and put her hand down and said, “You look like you need to put your head on the shelf now, dear.”

“I’m sorry?”

“Put your head on a shelf. Take a break? Stop thinking for the day, you know.”

I frowned.

“Rest your mind, sweetie,” she said and she moved on. Words of wisdom from a stranger, but I didn’t have time to rest yet; that’d come years later.

On my way back to the library, my phone pinged to tell me I was late for an orientation I’d completely forgotten about, and I stopped and looked around me, lost again. I felt old. I felt like I wasn’t going to be able to keep up. How would I manage classes and single parenting and being the pastor and preaching and visiting and paying for all those books and driving? It was too much. What was I thinking? The next day I’d be signing papers to buy a house on a part-time salary and school loans. The students around me were twenty and thirty years younger and most were accustomed to the changes on college campuses that threw me, like salad bars in the cafeteria and computer charging stations everywhere. Those students didn’t seem lost.

I sat down on a bench, defeated. I would have just quit right then and there, if I could have found the damn Divinity School building. Obscenity doesn’t count if no one hears you, right? I would be walking into the orientation with the other 60-plus students who would be in my cohort for three to four years. Only I’d be late, sweaty, disheveled and feeling defeated. I sat on a stone bench and looked at the backpack I had been steadily filling with more and more, mostly because I couldn’t figure out how to make the locker work in order to leave some of the many required books in there. Tears filled my eyes as I began to pray.

“I can’t do this, Lord. It’s too hard. I don’t know what I was thinking. I was foolish to even consider I could manage. I still had a house to close on and God knows that process never made sense to me. How am I gonna manage that AND Divinity school? I can’t even find the damn school.” I was trying not to just start sobbing.

I took a breath and looked up at the elderly and majestic magnolia tree shading me, one that had been planted with a couple of hundred other southern magnolias in 1895 by Bishop McTyeire, one of the bishops buried near the Divinity School. I squinted to look through the dark leaves at the sun shimmering and the cross…. Wait. What?

There was a cross on top of that building.

Suddenly, I was laughing as I cried. Of course, there was a cross on the top of the Divinity School Building! My guess is that everyone else knew that, except those of us sitting in our self-pity piles. Geez. Yeah, I’ll cop to a tendency to self-pity, fueled by a glass half full mentality. Sometimes I’ve wondered how I ever got anything done, but, then again, I’ve always been teachable. I wasn’t alone like I felt I was either, but there’s seldom been room for or recognition of any company in my self-pity dinghy.

In that moment, sitting on that concrete bench, though, laughing at the shiny cross against the blue sky, I kicked myself. Had I taken a moment to look up and to seek God in the midst of my exhausting week, I would’ve seen it. Like on the steeple of a Christian church in most places, shiny and bright, that cross topped the Divinity School building, there to guide us all day back home, like the North Star. I would have seen it if I had just looked up, if I had started my days with an awareness of God’s presence.

The rest of the week would be mostly a blur, but by time I stepped back into the pulpit that next Sunday, I would have “celebrated” or “survived” three momentous life changes in the course of one week. I was living in a new home, divorced, and a seminary student, but I was still standing, gratefully. I shared with my congregation about looking up and seeing the cross and realizing it had been there all along waiting for me to notice. I also shared the image of putting my head on a shelf. Both would carry me through the next four years of school as well as the decades I’d spend in ministry, reminders of who brought me to that moment and who would guide me through all the struggles, if I would pay attention.