Christmas swings like a pendulum do….

My paternal grandmother, Arbaleta (Grandma Leta), and maternal grandmother, Marie (Grandma Ree), could not have been more different creatures, and this was never more obvious than at Christmas. At first glance, it seemed to me that they were polar opposites when it came to wintry holidays especially; in retrospect, it is evident they were each on opposite points of the pendulum that has come to symbolize Christmas for me. Generation after generation on both sides of my family seemed to be unconsciously caught up by the wild swings of this holiday pendulum, a reactionary arc between a resounding “Yes!” to Christmas and its counterpart, an adamant “Hell, no!”

Finding Healing Around Christmas

Maybe your family needs some healing around holidays as well. Sure, it seems strange to talk about Christmas amidst all the paper and ribbon and cookies and tinsel, but it is, in fact, the best time to step back, recognize struggles and disappointment and start our families on paths to peace with Christmas; maybe along the way we could even figure out what’s “enough” for joy. I offer this reflection then to all our families because we cannot find healing if we do not know our family’s wounds. Here’s hope for discussions about upcoming celebrations: may they be intentional, loving and truly joyful for all.

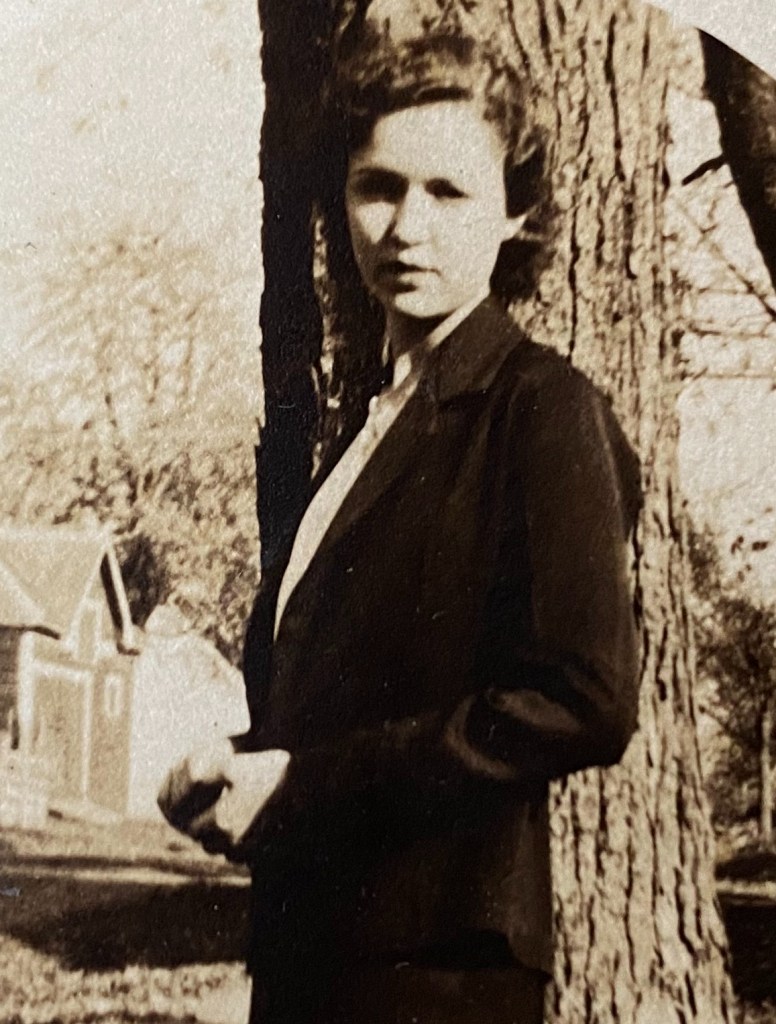

For me, it seems the best place to start is with the grandmothers. Both of my grandmothers were born around WWI; each married during the Great Depression. Neither had, as they say, “a pot to piss in,” not while they were growing up and not while they were young mothers. Both worked hard to support their families outside the home as well as in. Dad’s mom, Arbaleta, had two children, a boy and a girl, nine years apart. Mom’s mother, Marie, had three daughters all close in age.

Arbaleta’s husband, my Grandpa Mac, fell from an electric pole when he was young and wasn’t supposed to ever walk again, but did, in great part because Arbaleta would not let him not walk. She reportedly insisted he move his legs and even moved them for him for months as physical therapy until he could walk and work again. While I was never close to Grandma Leta, I have always admired the steely determination that these actions showed.

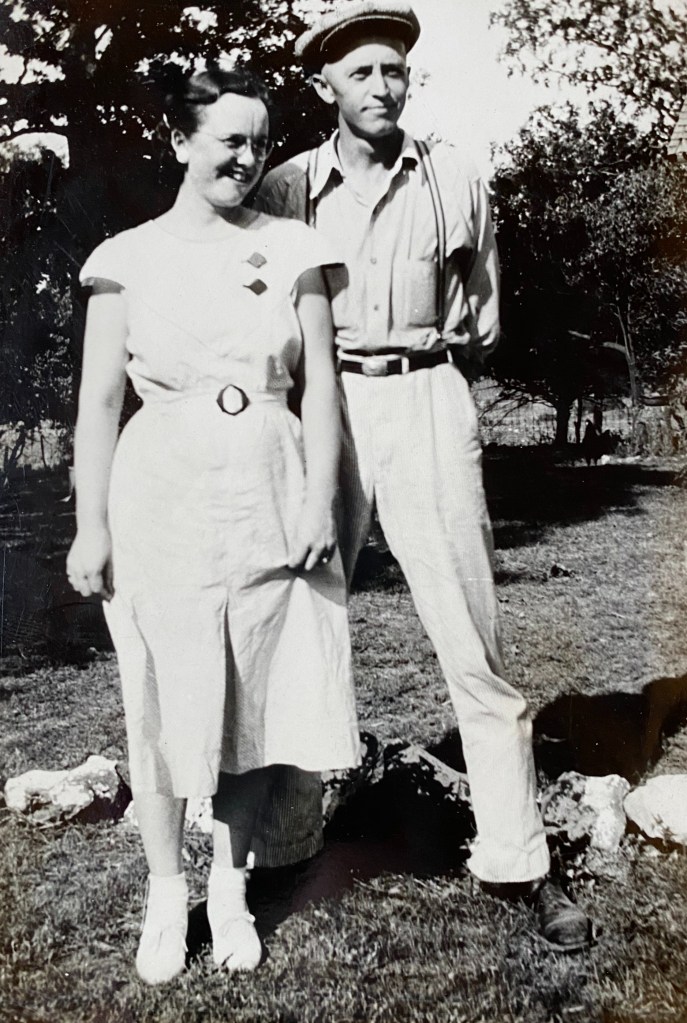

Marie had a husband who was always on the road as a truck driver, mostly because the bus or truck driver jobs close to town weren’t well-paying. He died of a massive heart attack at age 50; she lived another 30-plus years and married her high school sweetheart, then outlived him and married another kind man when she was eighty. At that wedding, the minister declared what we all knew, “Marie is a hopeful woman!” Grandma Ree, as we called her, was the quintessential kindergarten teacher when teachers still had time for nature walks, ironing leaves between sheets of waxed paper, and silly songs. Thus, she was the kind of grandmother I aspired to be: she played games with us, prayed for us, encouraged us and defended us when necessary. For most of her life, she modeled a love of learning: she earned a master’s degree, helped “plant” two churches, became an accomplished painter and was memorizing her favorite Bible verses in her seventies because she was losing her eyesight.

While I know little of Arbaleta’s childhood except poverty and hardship, I know Marie helped her mother run a boarding house after her chiropractor father divorced her mother, something which mortified both women.

That I’m aware of, Arbaleta seldom left her home after we were born. At least we never saw her leave her home, though, as far as we knew, she was perfectly capable. Our collective memory of her is of her seated on the sofa in her silk pajamas. Every time we visited her, we would wave to her from a few feet away as she perched on the sectional sofa in the corner, surrounded by shelves of various sizes and shapes of cacti. In one hand she held a lit cigarette, ashes threatening to crumble onto the silk, and the other hand held the ever-present bean bag ashtray (you know, the kind that has the bean bag on the bottom and the colorful aluminum tin bowl on the top.) That I can remember, she never once kissed, hugged or touched us in any way, shape or form. And, though she was pleasant, there were no memorable conversations, just the cloud of cigarette smoke that circled above her.

As for Christmas, well, I can’t remember there being much of it in their home at the edge of a Kansas golf course where she and Grandpa had retired. Ironically, I’m not aware Grandpa played golf, though my Dad did well into his eighties. As far as Christmas goes, Arbaleta represented the point in the arc where celebration was merely tolerated. Every few years, our parents would tote our gifts to their house to open on that rare occasion we woke up there on a Christmas morning, but the mood in the house was that Christmas decoration was, well, perfunctory. There was a tree and maybe a wreath, but evidently, for Grandpa and Arbaleta, a tree and some lights outside were “just enough,” though I suspect they were only put up to satisfy us. If overcoming poverty was Arbaleta’s life goal, she met it, thus the home on the golf course as well as the purchase of a new Lincoln every year. Secular or religious, it didn’t matter; Christmas was a formality, expected, tolerated for the children. Christmas dinner involved polished silver and store bought sweets, if any. “Please wait until you have permission to touch.”

Arbaleta died when I was seven and, suddenly, the focus of Christmas on my father’s side of the family shuddered and swung hard to the opposite extreme. Her daughter brought in Christmas every year from then on with a vengeance, lovingly, but with an overwhelming force. Every year, my aunt seemed to be competing for best Christmas ever, ostensibly in response to her own mother’s lackadaisical attempts.

While certain treasured and expensive statuary graced my aunt’s mantle for Christmas, for example, every year, the Christmas tree itself, usually the biggest tree I’d ever seen, sported a different theme with new, all handmade ornaments. I often asked when she started making them, sure she must have begun the previous New Year’s Day. She also made most of our gifts; they were always of Pinterest quality and I treasured several sweaters she knitted for me, for example.

As if it were necessary, she also became an amazing cook and thus, Christmas visits always involved impressing us with recipes for new dishes. Ironically, my mother didn’t want the recipes and my mother’s mother, Marie, didn’t need them; my mother was too busy leaning into that dysfunctional pendulum that was swinging back to the starker side, likely in reaction to her mother’s seasonal excess.

Marie, my mother’s mother, was on that same swing of the pendulum as my aunt, though I believe Grandma Ree went all out for her Christmas celebration for different reasons. Her husband, Grandpa George, also died when I was seven, but that did not slow Marie down in life or around the holidays. From the moment you opened the door into her home at Christmas, the scent of pine and wild berry candles carried you through room after room of greenery, holly, bells, poinsettias and new figurines or miniatures each year. Also new each year were the sweetbreads and cookies and homemade candies, all awaiting our discovery after hugs and kisses were exchanged and the coats and mittens and caps were piled onto a bed in the back of the house.

Grandma Ree with her brother, Mother and Sister, c. 1960’s.

A Family Nightmare

While Marie’s response seemed to me to somewhat resemble that of Arbaleta’s daughter, the driving force behind Marie’s likely unconscious Christmas reverie gone amuck was a well-kept secret, a family nightmare. On two separate Christmas Eves, during her childhood and youth, Grandma Ree had lost family members to suicide. I was, of course, an adult before I was made aware of that history or the details: one drank poisoned alcohol and one shot himself, both on separate Christmas Eves. Of course, the grief and shock of their actions was complicated by their (conscious or unconscious) efforts to ruin Christmas forever for some of their family.

How painful were their memories of the holidays?

Before we assume that Marie’s attempts to reclaim Christmas was the reason for the pendulum’s extreme movements, though, we need to recognize that some calamity in earlier generations drove those men to choose Christmas Eve to end their lives; we have to ask how painful were their memories of the holidays that drove them to risk also ruining the holiday for their spouses and children? How far back did the pain begin and what don’t we know about that?

In other words, it’s not likely either man, both of whom must have been suffering and feeling hopeless, started the family on that path.

The result, though, seems to have been an unconscious struggle to compensate. Those grand swings between holiday excess and hopelessness left subsequent generations still unconsciously at a loss to figure out what’s enough celebration. Further, while we can understand what might have spurred Marie’s need to excel at Christmas, I’ll likely never know what caused Arbaleta’s lack of enthusiasm for the holidays, and so I’m left simply to marvel at the overwhelming force of her daughter’s frenzied Christmas efforts. Sadly, or thankfully, no one now has picked up that mantle and the extended family is so fractured as to make these discussions nearly impossible.

I offer these reflections then to my nuclear family as the beginning of some discussions around conscious choices rather than wild reactions.

How does a family figure out what’s enough Christmas when the family’s history is, well, fractured? My own efforts were often emotionally unsatisfying; not only were my mother’s Christmas efforts headed for the stark extreme in reaction to her mother’s and her sister-in-law’s excesses, but they were complicated by my general lack of interest in cooking or baking except when absolutely necessary.

It was my ex-husband who started me thinking about some of our responses to holidays years ago: he protested the idea of Valentines’ Day for example, saying we could and should give one another cards or flowers or candy at anytime of the year and not just one day chosen by candy and card companies and florists. Yes, we can, I agreed wholeheartedly. But do we? Of course not, I pointed out. To his credit, he came by his dislike and struggle with holidays honestly and thus brought his own reactions to our holiday table: his birthday is the day after Christmas, and he was one of six children. His Christmas gift always came with a declaration that, “Oh-that’s your birthday gift too.”

Over the years, I certainly have struggled with holidays, whether it’s decorating or preparing a feast or just planning. Don’t get me started on birthdays for children; too many of those ended in my tears from exhaustion and a sense of failure. Did I tell you about all the “Pinterest Fails?”

All these things and more (all these things and more) that’s what Christmas means to me, my love….)

Stevie Wonder

Plenty of us struggle with the holidays, though, whether because of grieving a loss or knowing you’re the only one who can’t afford the gift exchange. I’ve tried over the years to make our gifts for Christmas but again, I know too many of my family members and friends were less than thrilled with the results. Mea culpa. We tried spreading the Christmas holiday over several days to lessen the wild two-minute frenzy of Christmas morning. We tried taking Christmas to the mountains; we tried staying home. We wondered what would happen if our family just gave up one Christmas and had lots of little ones? Could that not translate into lots of chances to do or give or be kind to one another? So many of our attempts at intentional Christmases revolved around not expecting one or two people to create a magical holiday that only left them in tears and exhausted.

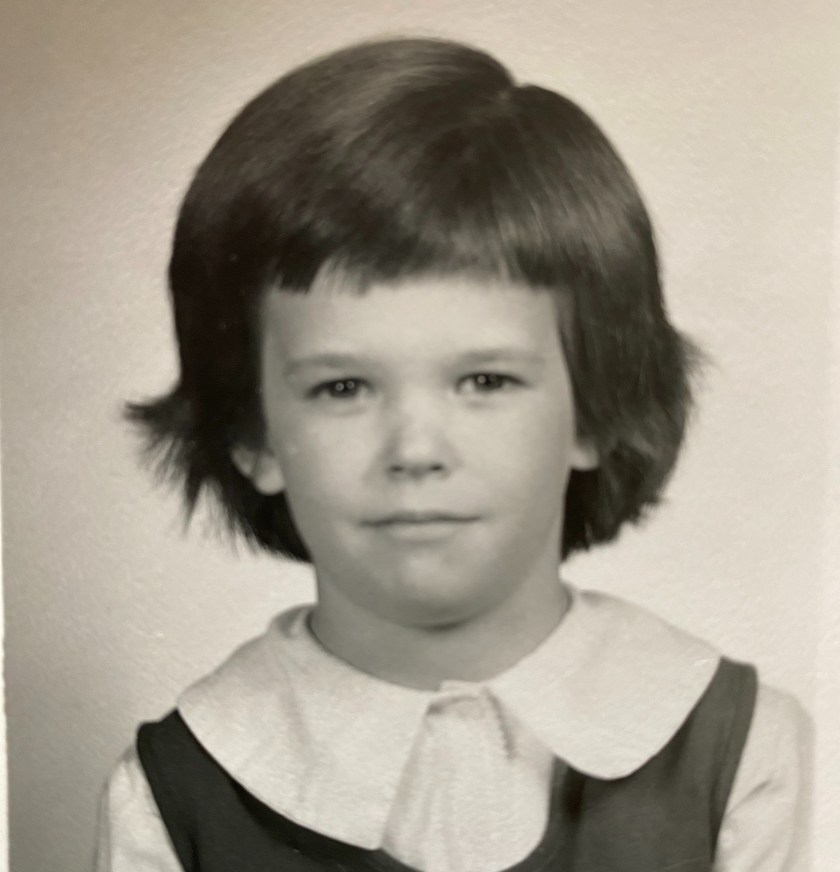

We’ve finally begun to incorporate some activities intentionally. Instead of china and crystal, we copied someone else’s snowman place settings, something the granddaughter and I could share. Last year, we started some silly story telling. This year, we introduced Karaoke and I am trying to reclaim the joy of baking by helping my granddaughter learn; watching her “knead” the goop she bought at the store made me think. Lo and behold, she discovered the joy of yeast and how it rises and how the baker must punch down the dough, then knead it. Her eyes grew wide after she made a fist and punched away. “That is soooo satisfying,” she said. A keeper.

In case you’re wondering, religion did not seem to figure at all in the wild reactions to the holiday through the years for my extended family. While Arbaleta was, as far as I know, agnostic, and Marie was a strong Christian, neither of them addressed or seemed to include the religious holiday in their efforts to reclaim or dismiss Christmas. For our family, that’s a different pendulum altogether. I personally love a good candlelight Christmas eve service singing and the idea that God came to be with us as an infant. Nevertheless, culturally we continue to struggle with all that Christmas celebrations have become for generations and we cannot heal from pain we do not acknowledge.

For our family, the faith and religious rituals are different pendulum altogether. I will never know why my Grandma Ree did not incorporate more of her personal faith into the celebration. Personal experience suggests she was treading lightly with agnostic family members and, as is true for many families, also celebrated on different days with different parts of the family, balancing church events with home. Nevertheless, culturally, we continue to struggle with all that our secular celebrations of Christmas have become for generations, often leaving us to begin another year frustrated, sad, discouraged. That is where we can start, but we must look collectively at this because we cannot heal from pain we do not acknowledge.

The best time, I believe, to reflect on how we celebrate Christmas is when we are all together…and we’ll before Christmas comes around-unexamined-again.

For my family, I continue to try to reframe Christmas in light of the history I bring to the holiday. I guess I hope through reflections and questions to step completely back from that wild, reactionary swinging between excessive celebration to indifference and even disdain.

I think one key is that we focus on the children, but with respect for their needs and not our own needs to give them the best holiday ever!

They get tired; we pay attention. They want to dress up; they don’t want to dress up. Quiet time, dancing in the kitchen time, gifts that involve us engaging with them. I’m not saying we’re the best with children ever or that ours are happier than any other. What I am saying is that like in so much of life, the children around me ground me. What they need is so often what I need. Let’s sing Jingle Bells, yes, at a gathering, but we mustn’t forget the bells themselves and our need to jingle them to make the song come to life.

A little percussion goes a long way and when we sing “Jingle Bells” there need to be jingling bells….A five-year-old taught me that.

Music must also be a source of holiday joy for many families. I’m jealous of those who manage a musical gathering but hopeful that might be in our future as well. Certainly with percussion everyone can participate! The idea of introducing music brings us back, though, both to the need for sensory awareness and to the idea of joy and reverie throughout the year. In order for there to be music next year, we need to practice throughout the year – often and, by practicing, remember the things that do bring us joy without wearing us out. I write this and share it now, after the holiday blitz, planning to share it with my family, to start the conversation we can have in anticipation of next year. I am curious to hear from them, and find out if they are aware of, or experiencing their own pendulum of Christmases, maybe even unknowingly riding that pendulum right now. I’m hopeful that with some lowered expectations of ourselves and a little yeast, we just might be able to rescue the holidays from the extremes of that dysfunctional pendulum my family rode for far too long AND decide for ourselves what is “enough Christmas.”

Leave a comment