Warning: parts of this post may trigger victims.

Take care of yourself.

Wise ones tell us that we often have to “learn” the same lesson over and over until we get it right. My hint: once you figure out whatever lesson it is you seem doomed to repeat in your life, get on that. Study it. Dissect it. Get it right so you can get it done, or, at least, get good at it.

For me, evidently, one lesson that I have felt doomed to repeat is “Speak up.”

In some ways, I credit/blame my ninth grade Speech and Drama teacher not only for teaching me debate techniques but also for getting me labeled a troublemaker. She asked me to argue in favor of the Equal Rights Amendment in the fall, which was still being considered by states for ratification. The main concept was consideration of equal pay. I honestly, as a pretty-self-absorbed teen, had not really considered any of the ideas that led us to the creation of that piece of legislation. I had never encountered the idea of women being treated as equally important and valuable or as the bearers of essential ideas and points of view that had been discounted and ignored for too long or as important and valuable as men. Like most of the women around me, I’d been raised to consider males the norm and females the “second run,” tolerated but not equal in much if anything. We were like fish swimming in the ocean of male dominance; until someone else from outside pointed out there were other ways to see the world, all I saw was the water in which I was swimming. For better or for worse, that assignment set my life on a course I could not fathom before.

Spoiler alert: we didn’t get there; the ERA was not passed by the necessary number of states.

Anyone remember the Equal Rights Amendment?

What I was reading to prepare for the debate was novel to me, but it made sense. I researched and prepared arguments in favor of this amendment as was the assignment, but on the day of the debate, I was embarrassed, disappointed, discouraged and hurt that the teacher allowed the opposing team to argue relying heavily on personal insults thrown mostly at me even though they learned the same rules we did about ad hominem arguments. Silly me. I had expected a fair and respectful discussion. I lost a couple of friends that day simply because I was trying to fulfill the assignment I was given, but even more disturbing to me was the aftermath of this debate: I was from then on labeled as a girl who hated boys, something that would crop up at the most unexpected times throughout high school.

Turned out whether or not I believed the arguments didn’t matter. What mattered was that I dared to consider them.

Suddenly, whether I wanted it or not, I was perceived as radical and even dangerous because of being willing to consider something as radical as equal pay for equal work.

I became, unbeknownst to me at the time, the poster child in our high school for “women’s lib.”

After a while, I simply embraced it. I even decided with some other girls to try out to be managers for the boys wrestling team because the wrestling coach, our history teacher, could not find boys who wanted to do the job. We all three got “hired” and we did the jobs, even earning our wrestling letters for our work.

Unfortunately, consciously or not, the wrestler I started dating decided I needed to be put in my place after we’d been dating for a few months.

Painful Lessons

Warning: This may trigger victims.

David didn’t have to say anything much at all. What he taught me while he held me down on that floor in my family’s apartment and raped me was that there was always someone stronger out there and they could overpower you if they wanted. It’s a lesson that’ll stick with you, make no mistake.

Within the scope of that lesson, there were others, all seemingly responses to the ideas of women being as free to be themselves as the men. “Be more ‘girly.’” “Be quiet when the boys are talking.” “Be available when your boyfriend wants you and be willing to do what he wants when he wants.” The lesson was a powerful one for me and I was, I know now, in shock afterwards; I went through the motions at school and at home.

It didn’t long to realize that the accepted rules were not ones I could live by. Because they were familiar, though, it took a minute to get to the real lesson. I needed to learn to say what I needed, to say no when I meant no and to say it regardless of whether or not anyone else agreed and as much as possible, in a safe way. This has become my life lesson.

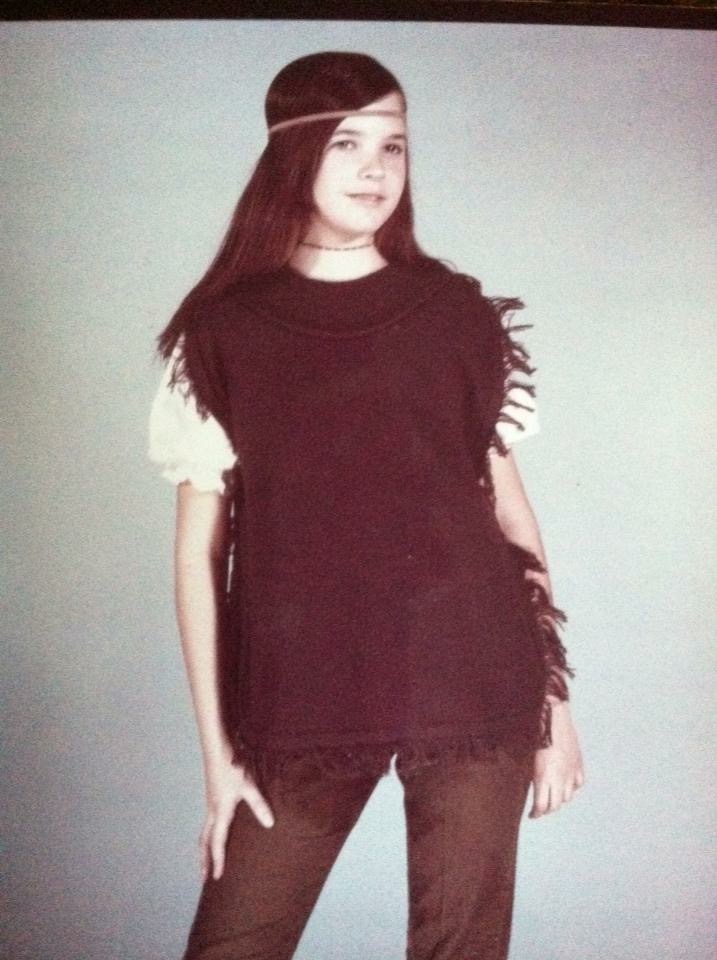

I was desperate after that to get him to leave me alone but I did not feel safe to share what had happened with my parents. I tried several times over the next few months to get him to leave me alone: I even cut my long hair and took to wearing cutoffs and sweatshirts, a move to seem even less feminine than I was; our mail carrier was convinced I was a boy. My attempts to “hide” did little good, though; he would wait until he knew I was home alone and then call and knock on the windows and doors and tell me through the door he knew where to find me when he wanted. I knew he was right. I had no one I believed would help, no one whom I believed would believe me.

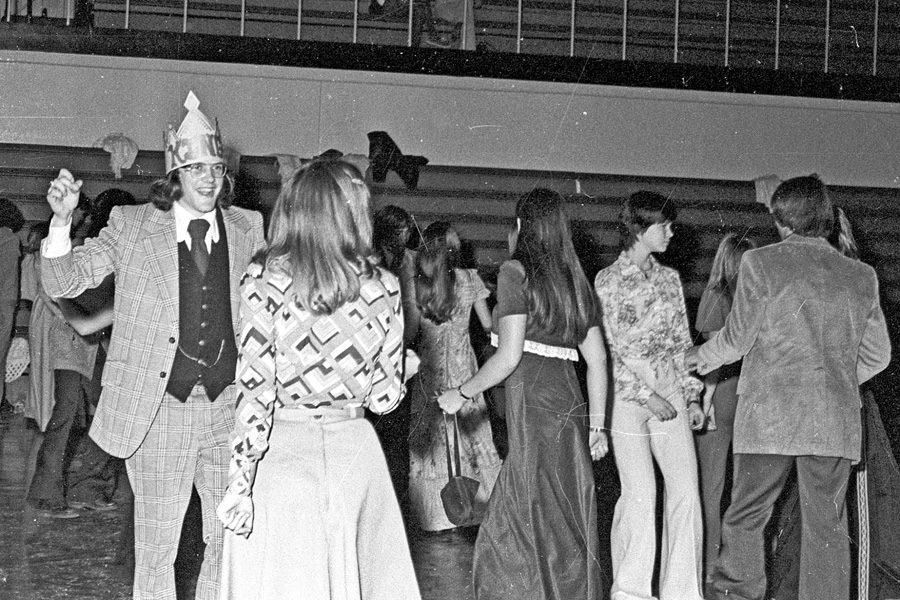

He was a wrestler, of course, which meant keeping my coveted wrestling manager position meant seeing him often. After a while, he changed tactics: he apologized. Where before he’d been angry and threatening, he became sweet and caring. He took me to meet his family. His little sister liked me. My little sister wouldn’t speak to me. His mother encouraged me to grow my hair out again and cooked special meals for me. We all watched “Laugh-in” together. I finally agreed to go with him to junior prom. We’d get to dance, something he knew I loved dearly. We’d get to go to after parties with others in our class; before he had never wanted to participate in group activities. On prom night, though, we danced one dance, took the prom picture, then left, I thought, to go to a friends’ party. Instead, he drove me to a cliff overlooking the Kansas City airport, nearly an hour’s drive from my home. He raped me again, then fell asleep. I crawled into the backseat and watched the occasional plane land until the sun came up and he took me home. When I walked into our apartment, my father was visibly disgusted, evidently certain I’d been a willing participant. I’ll never know if our speech teacher knew what that assignment on the ERA had set into motion. I’ve never told her what I learned about the cost of speaking up or how long it took me to learn to push back, stand up and speak out.

Dropping Out/Finding A Safe Place

At the end of that junior year in high school, my high school “career” ended. People are often surprised to find that a person who’s earned a master’s degree “dropped out” of high school. Actually, though, I didn’t quit high school as much as I gratefully moved on. My family moved from North Kansas City to Springfield, Missouri when I was headed to my senior year. The move was disappointing because I had been chosen for the yearbook team at my old school, but I was also grateful. And hopeful. My hope was to be away, finally, from him. Imagine my horror when he showed up one day in the beginning of that first summer after we moved, standing at my front door with one of the other wrestling managers; she had told him where to find me. I remember clenching my teeth for an entire afternoon while we “visited.” I had no intention of doing anything that might require me telling my parents what I did not want to tell anyone and he likely knew that. I was grateful when they simply left and I did not hear from him ever again. I didn’t need to. He would haunt my thoughts for years until I was able to get help and start evicting him from any thoughts, conscious or unconsciousness.

The rest of that summer would involve figuring out how not to face a senior year at a new school when I knew no one and I was the youngest kid in class. (I would turn seventeen in my senior year because I’d gone to a church kindergarten where they didn’t mind if I wouldn’t turn five til the end of November; the only requirement had been that I could tie my own shoes.) In addition, the high school I was leaving had been non-traditional in that we attended classes on a college schedule and were free to come and go as if we were in college. I had no intention of going back to a traditional school schedule once I’d grown accustomed to keeping my own schedule.

Looking for a new start…asking for help.

By mid-June, I’d decided to check into GED classes. “Why not,” I figured. High school had not been particularly friendly. College held the promise of starting out simply as the skinny girl with freckles in search of open minds and greater variety of interests and personalities and experiences. College was my chance to leave the provincial and limited nature of high school and be reminded that everyone in the world was not of one mind on much of anything. I looked forward to finding I wasn’t as alien or as weird as the next-door neighbors seemed to think. First step was being legally allowed to quit high school. At that point, I didn’t care one bit about being labeled a quitter.

I quickly found myself in a small classroom in that summer before what would have been my senior year, being tested to determine if I would be eligible to take the GED. Four of us were testing, including myself, a twenty-something guy in a leather jacket asking me if I wanted to see his switchblade and two folks who’d recently moved to the country. I was sixteen and wouldn’t even try to get my driver’s license for another year because I knew once I did, I’d become the chauffeur for my brother and sister. I rode a ten-speed bicycle everywhere then, easy enough in Springfield. In the GED class, we were given a paper test and told to bring our copy to the teacher’s desk when we completed it. She would score our test, then divide by 4 to determine if we had scored at a 12th grade level. If we hadn’t, we’d be offered remedial work to help us make the grade. Being seated next to “switchblade guy” probably spurred me to complete my work quickly, and I took my test booklet to the teacher.

“Wait here,” she said, so I stood next to her desk as she graded my work. “It won’t take long before we know if you need more studies.” I’d completed my junior year back in Kansas City on the honor roll and was hopeful until the teacher wrote my score on the top of the page. “Grade 11 equivalence. Remedial work needed,” she wrote.

As she reached into her desk drawer, ostensibly for some remedial resources, though, I peeked at her tabulations, took a breath and pointed to her numbers, whispering so the others wouldn’t hear.

“Excuse me, but your long division is wrong: forty-eight divided by 4 is twelve, not 11.” I wondered if her job required a high school diploma.

She slammed the drawer closed, looked at her calculations, and told me to come back at 8 a.m. Saturday for the GED. I elected to leave before my classmates had time to comment. I am proud to say that my school work prepared me well because I passed the GED easily.

The next step then was to convince the local college to admit a sixteen-year-old. Somehow, it did not occur to me that they’d hesitate. First, the admissions office informed me, I would need to take an ACT before enrolling. Since the next openings weren’t until October, I’d be lucky if I managed to start classes before January, and that was only if I tested well enough, I was told. I felt pretty discouraged, but by this time I could not imagine going back to high school. I don’t remember why, but I decided to write to the only educator I could think of who might help me. Dr. Kahler was the principal of the school I’d left in Kansas City and a long shot: while I had good grades and had scored well on the Pre-SAT, my only personal encounter with my high school principal had been when I was hitch-hiking to school one morning. Imagine my surprise when a car stopped and I opened the passenger door only to see Dr. K. He then gave me a ride to class and a lecture on the dangers of hitchhiking. (This was in the 70’s. We hitchhiked in our bellbottoms. Strangers were, sadly, the least of our worries; we had to be more afraid of the men we knew.)

I wrote to him, though I didn’t even know if he would remember me, and told him I was trying to enter college that semester rather than attend a high school where I knew no one for my senior year. I told him I’d passed my GED and what the school said about my needing to wait until the next year. I doubt it was an eloquent letter; I simply recounted my efforts to move ahead in school. I heard nothing for a month, then in early August, nervously opened a letter on the stationery of my former high school. Dr. Kahler wished me well and included a copy of a letter he’d sent to the college, evidently a few weeks prior. I got on my bike and was at the admissions office within the hour. Yes, they’d received the letter, I was told. From the exasperated tone, though, it seemed likely they were not going to go out of their way to mention that to me, but, since I was there, the admissions office reluctantly agreed I could enroll on probation pending the results of my ACT in October. I sent back a note thanking Dr. Kahler. I also sent him an update and thank you note at the end of my first semester after making the honor roll.

This was one of the first times I can remember speaking up, asking, over and over, for what I felt like I needed. Small steps maybe but steps nevertheless. Speaking up was not a quality I’d learned at home, though, and I know enough now to say I was taught to be a good victim long before I met that wrestler.

Most of my life, I had been the child who figured out quickly how to avoid being punished, who hid quietly to the side to keep from incurring any wrath on difficult days, who toed the line closely, even when the line seemed to change at random moments. My brother and sister more often were in trouble; they seemed to operate on the theory that any attention is better than none while I made it my goal to stay in the shadows.

As I began to step out into the real world, though, my parents were appalled to find I did not in fact always comply quietly, did not keep my head down, and did not just acquiesce and move on when I disagreed, at least not in the workplace. The first time I remember speaking up as a quasi-adult, in fact, I got fired.

After working in a fast food store at half of minimum wage, I doubled my paycheck by donning a sailor’s white middy with a red, white and blue sailor collar to serve fish and chips for a pirate-inspired franchise. In our blue skirts and knee socks and white sailor caps, we worked around fryers and hoisted benches up onto long wooden tables so we could mop underneath them. We reeked at the end of our work shifts of sour milk after tossing oversized trash bags leaking coleslaw dressing into the dumpsters. I was in my first semester of college and worked thirty-plus hours a week along with two other girls who attended a local Bible college. The job was ideal for them because we provided our own skirts and, with all the bending and lifting, longer skirts were helpful for modesty for me. For my two co-workers though, knee-length skirts were required by their school in order to be allowed to work there.

Nevertheless, it was the 70’s; while maxi skirts were popular for school or a Joan Baez concert, shorter was better for uniforms, it seemed. The “Fly Me” campaign was still fresh in our collective memories and plenty of folks thought any feminist protest over that kind of advertising was just, well, for troublemakers. After working there for several months then, we received notices that, beginning the next week, our skirts must be at least five inches above our knees and no more knee socks. Pantyhose only. No discussion. The two girls from the Bible College would have to quit. I naively thought we could reason with the Corporate offices. I wrote a letter. Polite. Reasonable. I explained how pantyhose were in fact dangerous around fryers, and short skirts made it difficult to bend and lift without flashing customers. I also suggested they would lose some honest, hardworking employees by making it impossible for thousands of students from Bible colleges to work at their stores. I mailed my letter on a Friday and worked all that weekend as usual.

Monday morning rolled around, though, and guess who was not scheduled to work at all? No explanation. No notice. Might have been a 70’s version of ghosting. I always wondered whether if that’d happened today, I might not have gotten some relief from being fired simply for writing a letter to corporate. Instead, my parents chastised me for being such a troublemaker and I went looking for another job after having been fired.

Speaking up in this case did not seem successful but it seemed right.

More importantly, for the first time, I could not stomach staying quiet, going along to get along, or looking the other way simply because that’s what someone else wanted me to do. This was new behavior, foreign to most of the people I knew and disturbing to my family for sure.

This life lesson continues to show up, often quite unexpectedly. While I am more adept at recognizing the need to speak up, it’s taken all of my life to get here and I still feel a deep discomfort saying no. I’ve learned, though, that learning to speak up has been as much for others in my life as it has been for me. I wish it were easier but I reason that, if it were easier, it would no longer be something to worry about. We’d all be able to speak up. We are clearly not there yet.

For more on this life lesson of learning to speak up, see the next installment: Facing the Big Dogs.